A Living Record

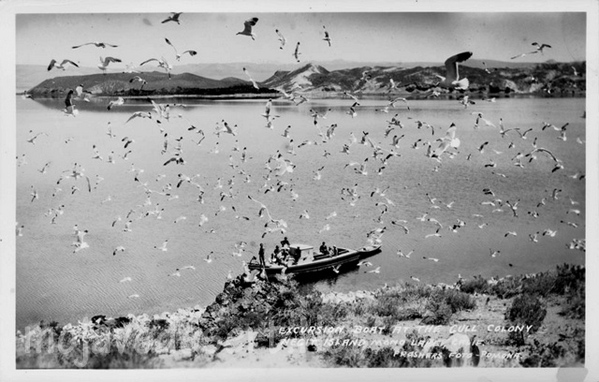

The Mojave Desert is the central thread, but the archive is more than just a storehouse of facts about the land. It’s a layered record, part historical survey, part natural history guide, and part personal journal. The archive contains thousands of entries, ranging from carefully produced histories of ghost towns to quick, almost casual notes about desert wildflowers. It also includes the memory of conversations, some technical, some reflective, all contributing to a living body of knowledge.

The current archive carries these notes forward. They do not simply add new entries; they revisit and renew older ones. When you ask about Scotty’s Castle, it’s not only a summary of a landmark in Death Valley but also a chance to look again at Walter Scott’s fabricated gold mine, his staged shootout at Wingate Pass, and the way his friendship with Albert Johnson turned into one of the strangest desert partnerships. That reflects the way your archive works: history is never sealed off, but constantly connected to other stories. Scotty’s fake mine ties to mining history, con men, railroad investors, and the enduring myths of the desert.

Other chats anchor themselves in place. Marl Springs, for example, appears not just as a dot along the Mojave Road but as a critical water source, garrisoned by soldiers in 1867 and attacked in the same year. The description in your archive emphasizes its clay-like soil and its dependable, if limited, water supply. The chat adds motion to that entry by pulling the soldiers into view, by describing how isolated Marl Springs was from Soda Springs to the west, and by noting how wildlife still depend on its water. Here, the archive preserves detail, while the conversation reanimates it.

Afton Canyon is another recurring subject. The archive refers to it as the Grand Canyon of the Mojave, formed approximately 15,000 years ago when Lake Manix drained catastrophically. The chats bring it alive with more than geology. They highlight the Mojave River flowing above ground, the slot canyons and caves, the risks of flash floods, and the chance to hike and watch wildlife. The personal tone slips in here: Afton is not just an entry on a map; it is a place walked, seen, and photographed. This blend of technical and personal is one of the hallmarks of your work.

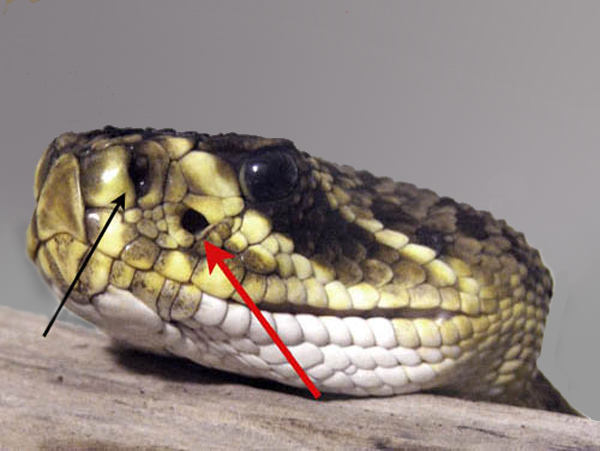

Rainbow Basin provides another good example. In the archive, it is a geologic site featuring badlands and folded rock, as well as paleontological finds and fragile soils. In conversation, it becomes a vivid picture of color bands, rattlesnakes, and the eerie feel of hiking through formations shaped by time and water. The description is simplified for younger readers when needed, but the detail remains. It is both a science lesson and a story about walking through the basin yourself.

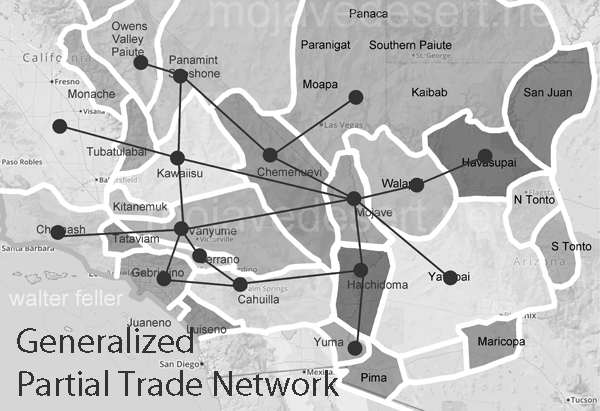

The archive also gives weight to local communities and their histories. Cajon Pass, for instance, is not simply a route. It is a crossroads layered with stories: Rancho Muscupiabe, Mormon pioneers, the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroads, the old wagon roads, the geology of Lost Lake and Blue Cut. Chats about Cajon Pass often focus on its function as a gateway, a place where history, geology, and transportation come together. They show how the archive not only stores information but also draws connections, creating a network of meaning.

The same goes for Old Woman Springs. The archive notes its name, given by surveyors who saw Indian women there. It records Albert Swarthout’s ranching operation, the cattle drives through Rattlesnake Canyon, and the later disputes with J. Dale Gentry. In chat, the place becomes more than history. It becomes a story of how ranching shaped the Mojave, how land ownership shifted, and how the desert landscape still carries those traces.

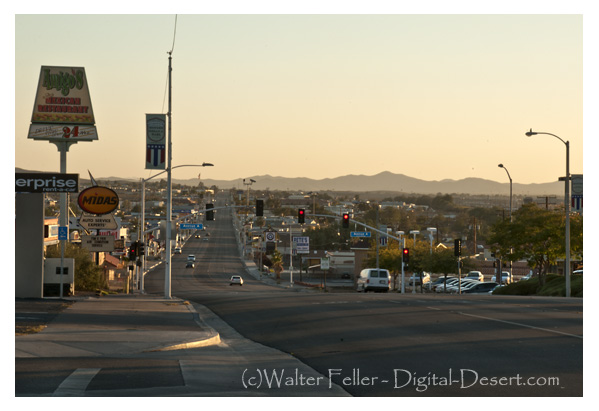

Other places appear again and again, sometimes as historical notes, sometimes as subjects for simplified explanations. Shea’s Castle in the Antelope Valley, built by Richard Shea in hopes of curing his wife’s illness, ruined by the stock market crash, later a film set. Hotel Beale in Kingman is tied to Andy Devine, the actor whose name became linked to Route 66. Oasis of Mara in Twentynine Palms is a site of Native planting, early settlement, and eventual park development. Each of these places carries weight in the archive, but they come alive in conversation, as the details are retold, refined, and made accessible.

Ecology is just as present as history. Pinyon pines and junipers, Fremont cottonwoods, brittlebush, desert sunflowers, bees sleeping in flowers, and ‘horny toads’ explained to children — all of these details show how the archive ranges across subjects. A glossary entry on igneous rocks can sit beside a playful description of bees tucked into golden blossoms for the night. A technical note on pinyon-juniper woodland succession can be followed by a casual story about antelope ground squirrels darting through camp. These shifts in tone are part of the richness of the record.

The archive also holds larger arcs. The history of Owens Valley runs through it: the water conflicts with Los Angeles, the aqueduct, the treaties with Native peoples, the battles fought during the Owens Valley Indian War. Panamint City and Greenwater appear as examples of boom and bust, with detailed accounts of stagecoach robbers, Nevada senators, mining camps, and the short-lived hopes of investors. The Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad, Remi Nadeau’s freight road, and the Atlantic and Pacific’s push across the Mojave all weave together into the bigger story of transportation. These arcs show how your archive is not just about single places but about the way places link into broader regional histories.

The present chats extend these arcs. A question about Owenyo might focus on its railroad history, but in doing so, it links back into Owens Valley and forward into the decline of rail in the desert. A question about Llano del Rio touches both the socialist dreams of Job Harriman and the modern ruin that still draws visitors. Each chat is both a piece in itself and a way of extending the larger web.

Throughout, there is an awareness of presentation. The archive is not simply a private notebook. It is shaped to be shared: titles, descriptions, metadata, glossaries, indexes. Chats often focus on how best to present this material to readers, whether as timelines, simplified summaries, or relational indexes. The act of shaping the material for public use is part of the archive itself.

The combination of archive and chat also reflects a deeper concern: preservation. The desert is full of forgotten places, and people who once told their stories are no longer around. By recording these histories, revisiting them, and reshaping them for new audiences, the archive resists that loss. The chats show the urgency of this work, as you reflect on volunteers thinning out, museums struggling, and the need to keep the desert’s stories alive.

The archive is a landscape in itself. Its mesas are the long, detailed histories. Its washes are the short, playful notes. Its valleys are the connections between subjects. The chats are the weather moving across that landscape, stirring it, reshaping it, sometimes eroding, sometimes depositing. Over time, the whole thing grows richer, more interconnected, more alive.

This is why the archive and chats cannot be separated. The archive preserves. The chats enliven. Together they form a record of both the desert and of the act of remembering. The Mojave is the subject, but the deeper theme is persistence: the persistence of asking, recording, and shaping knowledge into something that lasts.

–