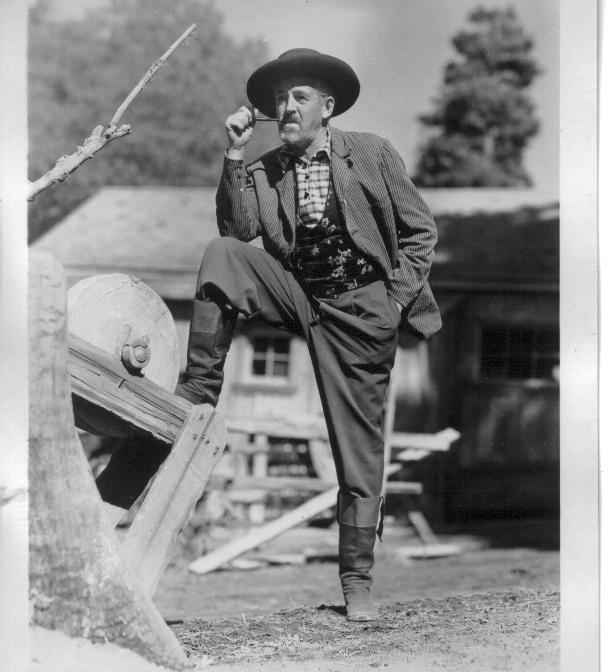

Charles Koehn, famously known as “Dutch Charley,” was a German-born prospector who became a prominent desert character in California’s El Paso Mountains around the 1890s

vredenburgh.org. In 1892, he homesteaded land at a desert water source called Kane Springs (later often referred to as Koehn Springs) with the intent to profit from the stream of travelers and miners between Tehachapi and the Panamint Range

publiclandsforthepeople.org. Koehn established a way station there that soon turned into a one-man desert outpost. In September 1893 he even secured a post office at his ranch (officially named “Koehn” post office) and began delivering mail to local mining camps at 25 cents per letter

publiclandsforthepeople.org. His station offered much-needed services: he ran a store and bar, sold staples like hay, grain, and meat to prospectors, and even provided free water to any traveler or teamster passing by

vredenburgh.org. This generosity and entrepreneurial spirit made Dutch Charley’s place a well-known stopover in the Mojave Desert. By late 1893, two stores were operating at Kane Springs alongside Koehn’s facilities, attesting to the little community that sprang up around his oasis

vredenburgh.org. Koehn’s resourcefulness and commanding personality earned him colorful nicknames such as the “Bismarck of the Desert” and the “Wild Dutchman,” reflecting both his German heritage and his formidable presence on the frontier

angelfire.com.

Role as a Prospector and Mining Claims

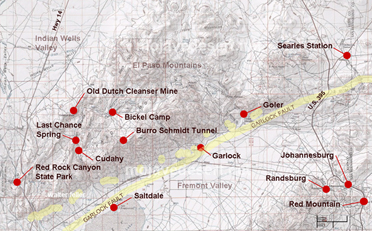

Despite primarily running a supply station, Dutch Charley was also an active prospector and mining man. During the 1893 gold rush in the El Paso Mountains (notably at Goler and Red Rock canyons), Koehn capitalized on the boom by supporting miners rather than striking gold himself

publiclandsforthepeople.org. In early 1896, he built a small stamp mill at Kane Springs to process ore

vredenburgh.org, one of the first mills outside of Garlock, though such mills were soon overshadowed when railroads enabled shipping ore to larger mills elsewhere

vredenburgh.org. Koehn’s true prospecting successes came from the desert’s less-glamorous minerals. He dabbled in borax: in 1896 he discovered a deposit of ulexite (a borate mineral) near his homestead and worked it sporadically over the years, though total production was only a few railcar loads of borax “cottonballs”

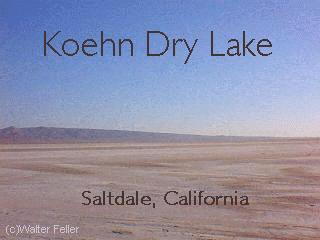

publiclandsforthepeople.org. His most significant find was a large gypsum deposit. In late 1909, Charles Koehn located an extensive bed of gypsite (a gypsum-clay mixture) in the dry lake adjacent to his ranch (now Koehn Lake)

publiclandsforthepeople.org. By 1910–1912 he had attracted outside interest in this gypsum; a small calcining plant started making wall plaster, and the California Crown Plaster Company produced the first sacks of gypsite from his claims

publiclandsforthepeople.org. Koehn began leasing portions of his gypsum property to various companies between 1910 and 1930 to be mined for plaster and agricultural additives

publiclandsforthepeople.org.

Aside from gypsum, Koehn also held salt claims on the dry lake itself. Koehn Lake (sometimes called Kane Dry Lake) was rich in surface salt, and Koehn had staked claims there in the early 1900s

vredenburgh.org. By leasing or working with larger capitalists, Koehn managed to derive income from these mineral claims despite not having the means to develop them entirely on his own. His ventures made him locally famous – if not for striking a mother lode of gold, then for uncovering the desert’s more humble riches like salt, borax, and gypsum.

Conflicts over Claims and Notoriety

Charles “Dutch Charley” Koehn’s mining ventures were not without conflict. His gypsite and salt claims led to fierce disputes in the wild lawlessness of the Mojave. In January 1912, a band of claim jumpers, backed by hired gunmen, attempted to seize Koehn’s holdings on the dry lake

publiclandsforthepeople.org

vredenburgh.org. This confrontation erupted into a gunfight on the alkali flats of Koehn Lake. Koehn, described by historians as “feisty,” stood his ground and won what was by all accounts a brief but lively battle

publiclandsforthepeople.org

vredenburgh.org. The aftermath of the shootout landed the instigators in court – the Randsburg Miner newspaper reported that T. H. Rosenberger and ten others were found guilty of forcible entry in the incident (effectively acknowledging Koehn’s rights) and were fined for their actions

vredenburgh.org. Ultimately, about a year later, Koehn reached a deal with his rivals: he sold his salt claims to Thomas Thorkildsen (one of the claim jumpers’ financiers), who then passed them to the Los Angeles-based Diamond Salt Company

vredenburgh.org. This resolution allowed an organized salt works to proceed at the site, while presumably earning Koehn some compensation. A local paper even headlined “Charles Koehn Sells Famous Salt Springs” in late 1912, marking a victorious end to that particular feud

vredenburgh.org.

Koehn’s battles moved from the desert to the courts in the ensuing years. With multiple companies leasing or coveting his gypsum deposits, contractual disputes arose. Various firms sued Koehn over percentages and rights; one such company, Alpine Lime & Plaster, demanded $50,000 in damages around 1920

publiclandsforthepeople.org. Legal skirmishes dragged on, but a far more dramatic incident occurred in 1923. That year, Koehn was arrested under alarming circumstances: he was caught fleeing the Fresno home of Judge Campbell Beaumont (who had been involved in one of the civil cases) and was accused of planting an explosive device there

publiclandsforthepeople.org. Suspicious evidence – a bomb with fuse and bits of newspaper – was allegedly found in Koehn’s car, though Koehn steadfastly proclaimed his innocence

publiclandsforthepeople.org. Despite lingering doubts about whether he was truly guilty, Koehn was convicted of attempted bombing. The aging desert miner was sent to San Quentin State Prison in 1924 to serve his sentence

publiclandsforthepeople.org. Tragically, “Dutch Charley” never regained his freedom – he died behind bars in 1938, just days before a scheduled release which might have pardoned his late-life transgression

publiclandsforthepeople.org. This inglorious end stands in stark contrast to his earlier years of desert independence. Nonetheless, his notoriety from the claim wars and the courtroom drama only cemented his legend in Kern County lore.

Dutch Charley’s Cabin and Desert Wanderers’ Haven

Throughout the turn of the century, Dutch Charley’s outpost at Kane Springs became a well-known haven for desert wanderers. His stone cabin (often referred to as Dutch Charley’s Cabin) served not only as his home and base of operations but as a reliable refuge for prospectors, travelers, and stagecoach drivers crossing the arid expanse. Reports from the Bureau of Land Management note that Koehn’s supply station included a rock house which may still be extant decades later

scvhistory.com. In the 1890s, this cabin and ranch was essentially the only “town” for miles. Koehn dispensed mail from the station until 1898 (when the small post office was discontinued as richer diggings at Randsburg drew away the miners)

vredenburgh.org

vredenburgh.org. Yet the site itself remained active; Koehn kept his ranch running for some 30 years more, and his stone cabin continued to be a landmark in the El Paso Mountains long after he was gone

vredenburgh.org. Travelers could stop at Dutch Charley’s place to water their horses at his well, rest in the shade of his porch, and perhaps hear a story or two from the garrulous host. He was known to give out water freely to parched passers-by and was generally hospitable – as one contemporary observer put it, desert wayfarers were “warranted to keep out the desert heat” at Koehn’s spring, which was “a veritable oasis in the desert”

vredenburgh.org

vredenburgh.org.

Koehn’s cabin-stopover also fostered interactions with many other desert characters of the era. He dealt daily with prospectors grubstaking in the El Paso range and the Rand District; men like the gold discoverers of Goler Gulch would have frequented his station. He was part of a network of desert personalities that included figures such as William “Burro” Schmidt – the lone miner who famously dug a tunnel through the El Pasos not many miles from Koehn’s ranch

publiclandsforthepeople.org. It’s easy to imagine Schmidt, during his 1906–1930 tunneling feat, stopping by Dutch Charley’s for supplies or mail. Likewise, when early Hollywood film crews came out to Red Rock Canyon (just west of Koehn’s place) in the 1910s and 1920s to shoot Westerns, it was Dutch Charley whom they contacted to rent wagons and mules for their movies

angelfire.com. He supplied produce from his garden to these crews and local mining camps, showing a surprisingly domestic side (cultivating vegetables in the desert) alongside his rough prospector image

angelfire.com. By serving as a hub for miners, wanderers, and even filmmakers, Dutch Charley’s cabin became embedded in desert lore as a welcomed stopover – a place of cold drinks, warm meals, and lively conversation in an otherwise desolate region.

Legacy and Cultural Portrayals

Charles “Dutch Charley” Koehn left an indelible mark on the Mojave Desert’s history. Several geographic landmarks still bear his name and attest to his activities. Koehn Dry Lake (north of California City in Kern County) is named after him and was the site of his salt and gypsum exploits

vredenburgh.org

vredenburgh.org. The site of his homestead, Kane Springs, is sometimes referred to as Koehn Springs on old maps, acknowledging his role as the founder of that desert settlement

vredenburgh.org. Even the short-lived mining camp of Gypsite (which grew around the gypsum diggings near Koehn Lake) owes its existence to his discovery – a California state mineral report noted that Koehn’s gypsum deposit covered about a square mile and was significant enough to be mined on and off for decades

publiclandsforthepeople.org. While little remains of “Gypsite” today, the ruins of Dutch Charley’s rock cabin at Kane Springs reportedly survived for many years; historians in 1980 observed that the stone house was “still extant”, a tangible relic of Koehn’s desert enterprise

scvhistory.com. The cabin site, though remote, is considered an archaeological and historical site within the El Paso Mountains, symbolizing the era of lone prospectors and desert hospitality.

In popular culture, Dutch Charley’s adventurous life has been portrayed with some creative license. An episode of the classic Western TV series “Death Valley Days” titled “One Man Tank” (1960) fictionalized Koehn’s story for television. In that episode, actor John Bleifer plays Dutch Charley Koehn as an aging prospector who, having failed to strike it rich in gold, buys a goat farm instead – only to inadvertently hit a gold vein on that very farm

conservapedia.com. The plot includes a scheming character trying to oust Charley from his property and a friend helping to fight the injustice

conservapedia.com. While this TV tale takes liberties (there is no record of Koehn ever running a goat ranch or belatedly finding gold), it reflects how Koehn’s persona had entered frontier folklore. The very inclusion of “Dutch Charley” in a 1960s Western show underscores his local fame; viewers were treated to the legend of a stubborn old desert rat whose luck turned in a fanciful way.

Beyond television, Koehn’s name appears in regional histories, museum exhibits, and guided off-road tours of the Mojave. He is remembered as a quintessential Mojave Desert prospector: resilient, shrewd, and a bit rebellious. Writers have alternately cast him as a hero of the desert (standing up to claim jumpers and aiding fellow miners) and as an outlaw figure (given the later bomb plot conviction). In truth, his life encompassed both aspects. Today, visitors to Red Rock Canyon State Park and the surrounding El Paso Mountains might hear about Dutch Charley when exploring sites like Garlock (where his mill once operated), Last Chance Canyon, or the Old Dutch Cleanser Mine – all part of the same historical landscape he inhabited. The story of Charles “Dutch Charley” Koehn – from immigrant prospector and “Desert Bismarck” to embattled claim owner and folklore character – is an integral chapter of California’s desert heritage, illustrating the grit, conflict, and community of the old prospecting days

angelfire.com

vredenburgh.org.

Sources: Historical mining accounts and archives such as Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining in the California Desert

publiclandsforthepeople.org

publiclandsforthepeople.org, the Randsburg Miner and other contemporary newspapers summarized in Vredenburgh et al.’s research

vredenburgh.org, as well as cultural references like Death Valley Days

conservapedia.com, have been used to compile the above information on Dutch Charley’s life and legacy. These sources document Koehn’s activities (mail delivery, mining claims, legal battles) and paint the colorful narrative of a desert character whose cabin became a Mojave legend.