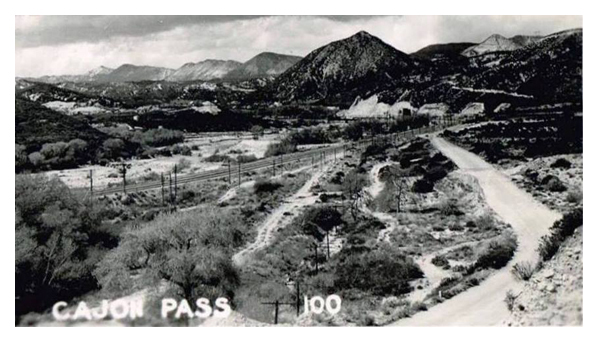

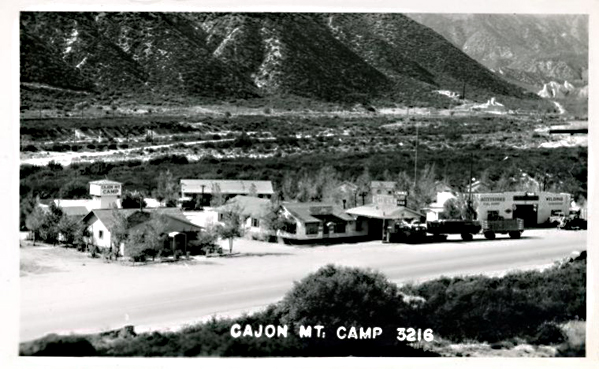

The Cajon Pass is a significant geographical feature located in Southern California, United States. It is a mountain pass in the San Bernardino Mountains, part of the Transverse Ranges in Southern California. The pass is approximately 60 miles (97 kilometers) east of Los Angeles and is a crucial transportation corridor in the region. Here are some key points about the Cajon Pass:

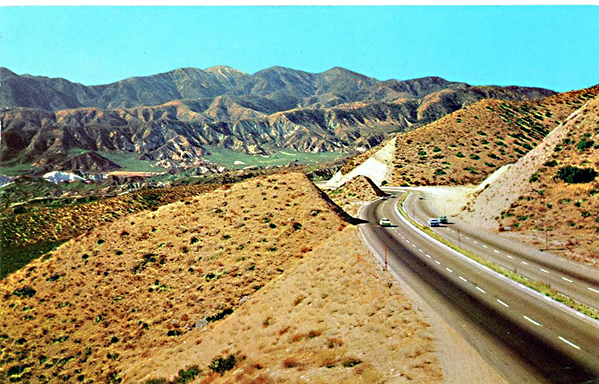

Geographical Location: The Cajon Pass is in San Bernardino County, California. It is part of Interstate 15, which connects the cities of San Bernardino and Victorville in the south to the High Desert region and beyond to Las Vegas, Nevada, in the north.

Transportation: The pass is a critical route linking the densely populated Los Angeles metropolitan area with the desert and the southwestern United States. It serves as a major route for both passenger and freight transportation. Numerous vehicles and freight trains pass through the Cajon Pass daily.

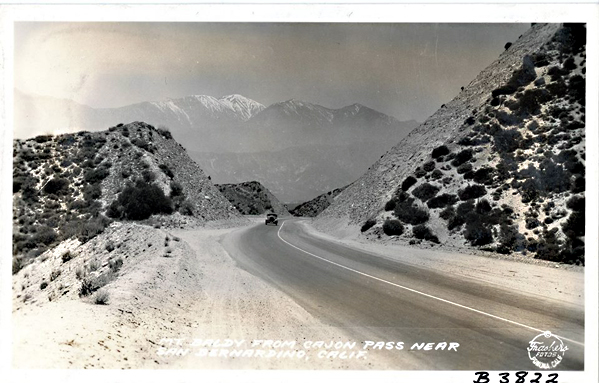

Elevation: The Cajon Pass rises to an elevation of approximately 3,800 feet (1,160 meters) above sea level. This elevation change is significant, and it makes the pass an important point in the regional geography.

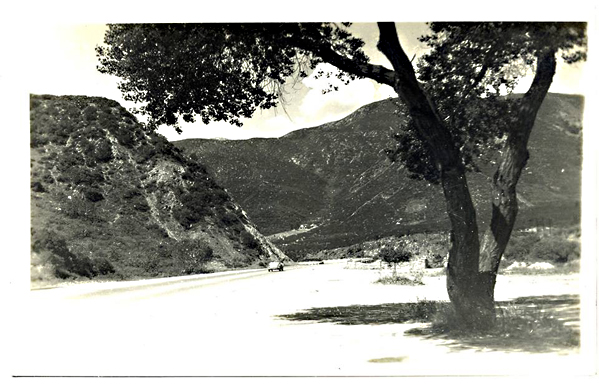

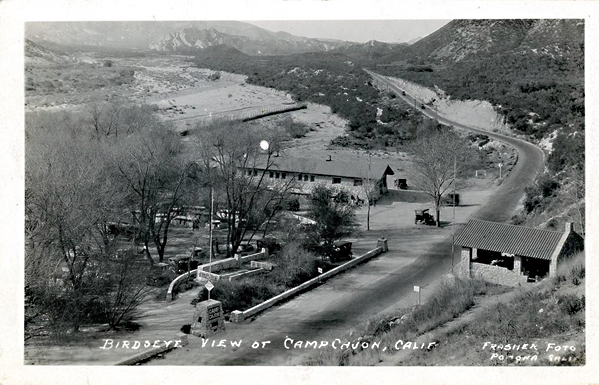

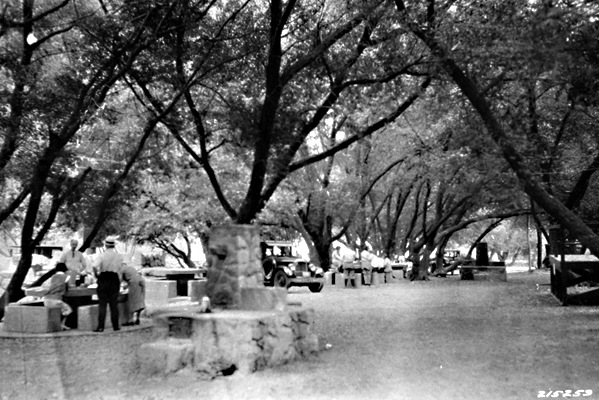

Natural Scenery: The Cajon Pass offers stunning natural scenery with its rugged terrain, including rocky cliffs and slopes. It is a popular spot for hiking and outdoor activities, providing beautiful views of the surrounding landscapes.

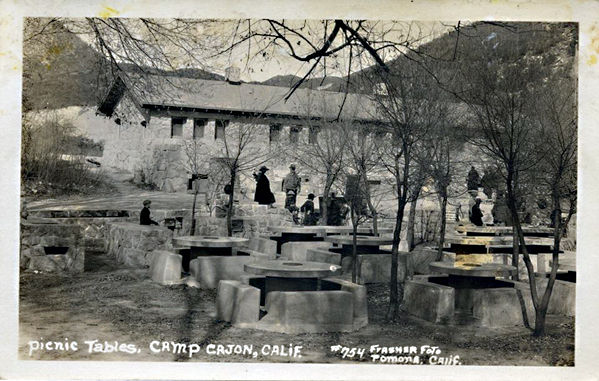

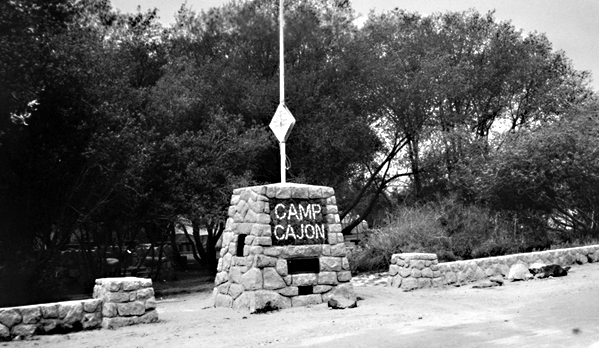

Historical Significance: The pass has historical significance as it was used by Native American tribes, Spanish explorers, and early settlers. In the mid-19th century, it became a vital transportation route for wagon trains during the California Gold Rush.

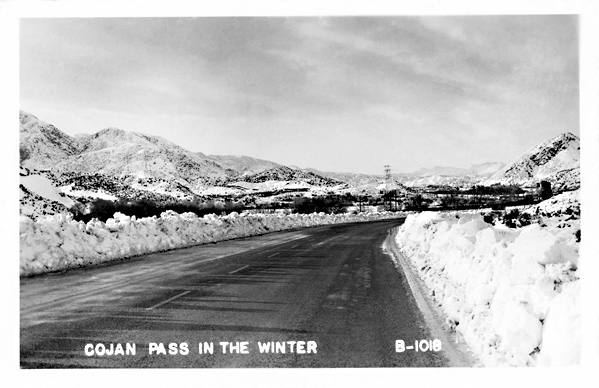

Climate: The climate in the Cajon Pass can vary significantly with the seasons. It can experience hot summers and cold winters, and snowfall is common during winter, impacting transportation through the pass.

Wildlife: The region surrounding the Cajon Pass is home to various wildlife, including desert bighorn sheep, often seen in the area.

Infrastructure: To facilitate transportation through the pass, major highways and rail lines traverse it. These include Interstate 15, California State Route 138, and numerous rail lines used for freight transportation.

Geological Activity: The Cajon Pass is located in an area with geological activity, including the presence of the San Andreas Fault. Earthquakes are a potential natural hazard in this region.

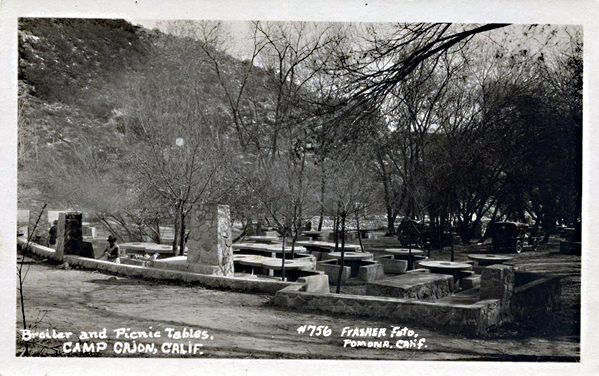

Recreational Opportunities: Besides its transportation importance, the Cajon Pass offers recreational opportunities, including hiking, rock climbing, and wildlife viewing for outdoor enthusiasts.

Overall, the Cajon Pass plays a significant role in the transportation infrastructure of Southern California, linking the metropolitan areas to the High Desert and beyond while also providing a natural setting for outdoor activities and appreciation of the region’s unique geography.

History

The history of the Cajon Pass is rich and significant, with a timeline that spans many centuries. Here is an overview of the historical events and developments related to the Cajon Pass:

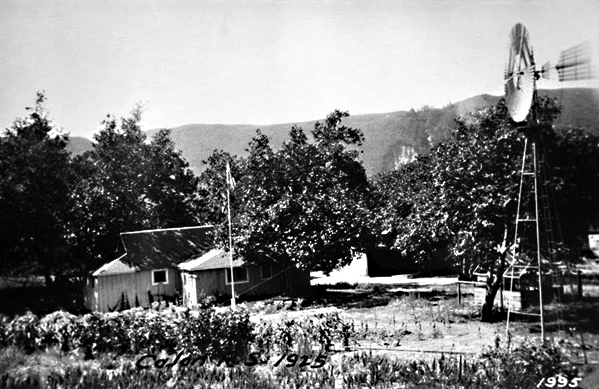

Indigenous Peoples: Long before European settlers arrived in the region, the Cajon Pass was inhabited by indigenous peoples, including the Serrano and Tongva tribes. These Native American groups used the pass as a natural corridor for trade and travel.

Spanish Exploration: In the late 18th century, Spanish explorers, including Father Francisco Garces and Juan Bautista de Anza, passed through the Cajon Pass during their expeditions into California. The Spanish established a presence in California, and the pass was an important part of their transportation network.

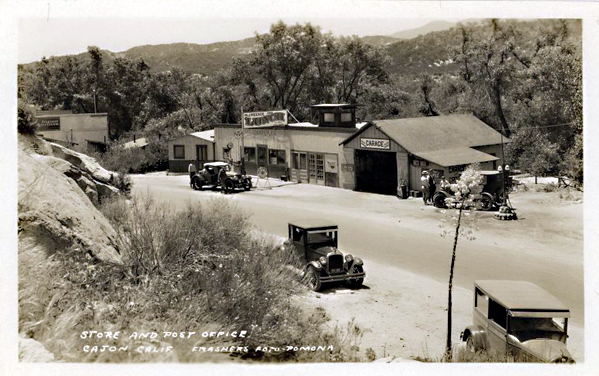

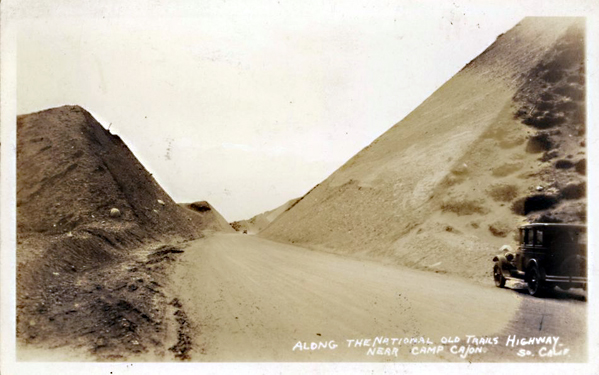

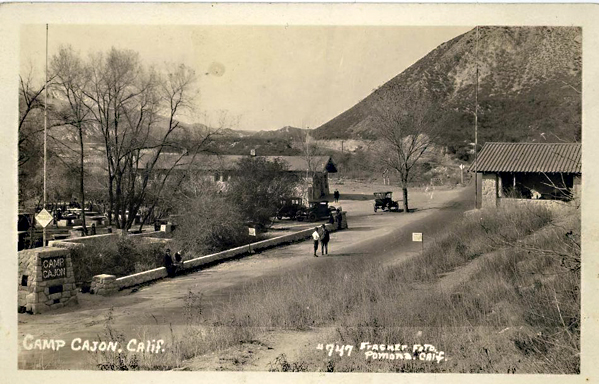

Early American Settlement: As California transitioned from Spanish to Mexican rule and eventually became part of the United States, pioneers and settlers used the Cajon Pass as they headed westward during the westward expansion period of the 19th century. It was a crucial route for wagon trains and the Butterfield Overland Mail Stagecoach Line, facilitating westward migration.

California Gold Rush: The discovery of gold in California in 1848 led to a rush of people seeking their fortunes. Many gold seekers, known as “forty-niners,” passed through the Cajon Pass on their way to the goldfields in Northern California.

Railroad Development: The construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad in the 1860s further solidified the importance of the Cajon Pass. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway, in particular, played a significant role in developing rail infrastructure through the pass, greatly facilitating trade and transportation in the region.

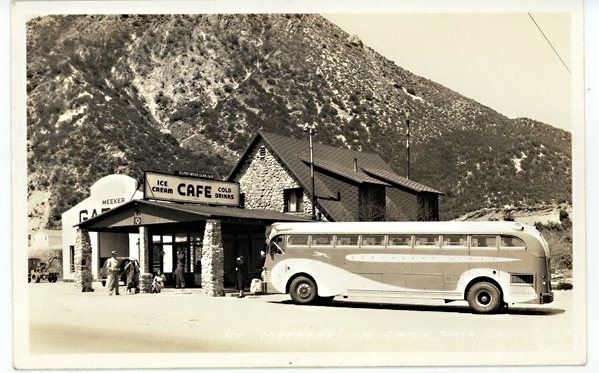

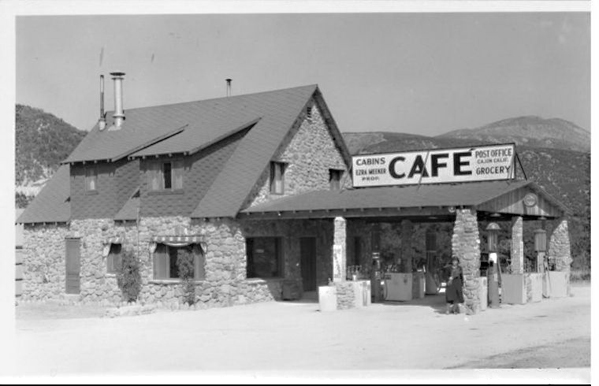

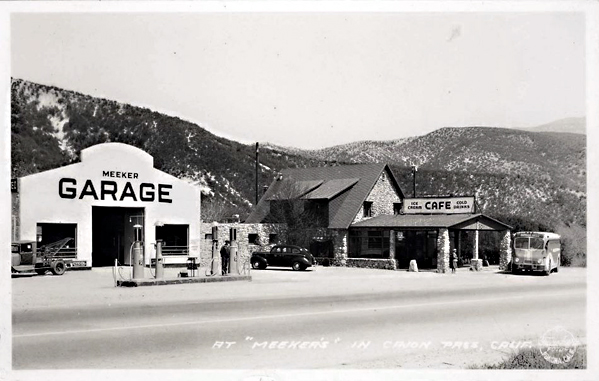

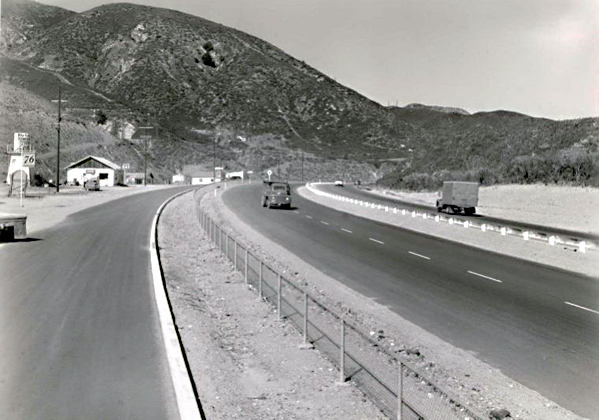

Modern Transportation: In the 20th century, the pass evolved as a transportation hub. The development of modern highways, including U.S. Route 66 and later Interstate 15, made the pass a vital link in the national highway system. It also became a major corridor for freight transportation.

Natural Hazards: The Cajon Pass is located in a seismically active region, and it has been affected by earthquakes throughout its history. Notably, the 1812 San Juan Capistrano Earthquake created a landslide in the pass, altering its geography.

Natural Beauty: Beyond its historical significance, the Cajon Pass has always been appreciated for its natural beauty and scenic vistas. Outdoor enthusiasts and hikers have enjoyed the pass’s rugged terrain and unique landscapes.

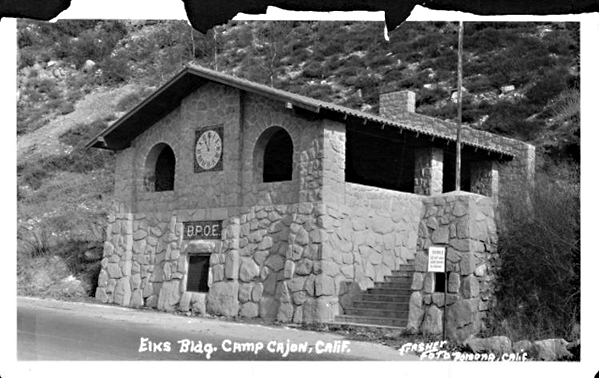

Cultural Significance: Over the years, the Cajon Pass has been featured in literature, music, and popular culture. It is often mentioned in songs and stories about Route 66 and the American West.

Today, the Cajon Pass remains a vital transportation link in Southern California, serving as a critical route for passenger and freight traffic. Its historical and cultural importance, as well as its stunning natural beauty, continue to make it a noteworthy part of the region’s heritage.

Geology

The geology of the Cajon Pass is a fascinating aspect of its natural history, and it plays a significant role in shaping the landscape and geological features of the region. The pass is located within the San Andreas Fault zone, which is one of the most well-known and active fault systems in California. Here are some key geological aspects of the Cajon Pass:

San Andreas Fault: The Cajon Pass is situated along the San Andreas Fault, which is a transform fault that marks the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. This fault system is responsible for the movement of tectonic plates and is associated with earthquakes in the region.

Fault Activity: The San Andreas Fault is known for its potential to produce significant seismic events. The movement of the Pacific Plate and North American Plate along the fault can result in earthquakes, and the Cajon Pass area is considered seismically active. This fault activity has influenced the landscape in the region over geological time.

Formation of the Pass: The Cajon Pass itself is a result of tectonic activity along the San Andreas Fault. Over millions of years, the fault has caused uplift and displacement, creating a gap or pass in the San Bernardino Mountains. This geological process has allowed for the formation of the pass as a natural transportation corridor.

Rocks and Geology: The geology of the Cajon Pass includes a variety of rock types, including sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous rocks. The mountains surrounding the pass are composed of various types of bedrock, including schist, gneiss, and granite, which have been uplifted and exposed due to tectonic forces.

Topography: The pass features rugged terrain, steep slopes, and cliffs, which are the result of geological processes such as faulting, erosion, and uplift. These geological features create the distinctive landscape of the pass.

Erosion: Over time, erosion, primarily driven by wind and water, has shaped the topography of the Cajon Pass. It has also exposed rock formations and created canyons and valleys in the area.

Waterways: The pass has been influenced by the flow of water, with several small streams and washes running through it. These waterways have played a role in shaping the pass and the surrounding landscape.

Geological Study: The Cajon Pass is of interest to geologists and seismologists who study the San Andreas Fault and its activity. Understanding the geology of the pass and its fault systems is important for assessing earthquake hazards in the region.

The geological features and the presence of the San Andreas Fault make the Cajon Pass an area of both scientific interest and potential geological hazard. The ongoing study of its geology contributes to our understanding of the complex tectonic processes at work in Southern California and helps with earthquake preparedness and mitigation efforts in the region.

Railroad History

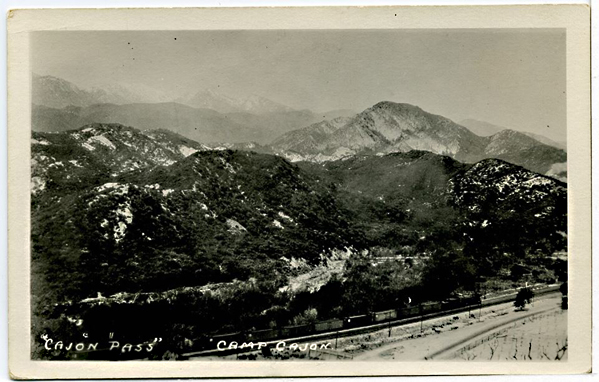

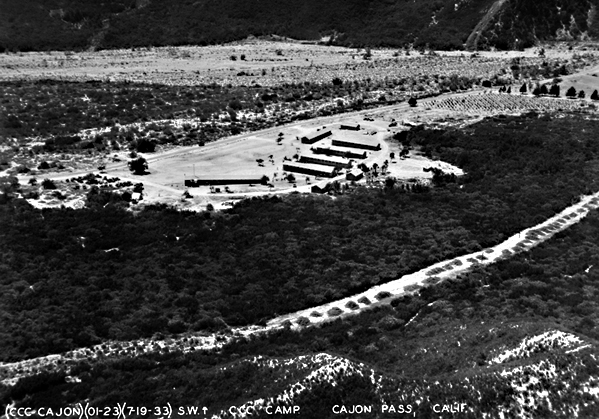

The history of railroads in the Cajon Pass is closely intertwined with the broader history of railroad development in the American West. The construction and operation of railroads through the Cajon Pass played a pivotal role in the economic growth and expansion of Southern California and the United States. Here’s an overview of the railroad history in the Cajon Pass:

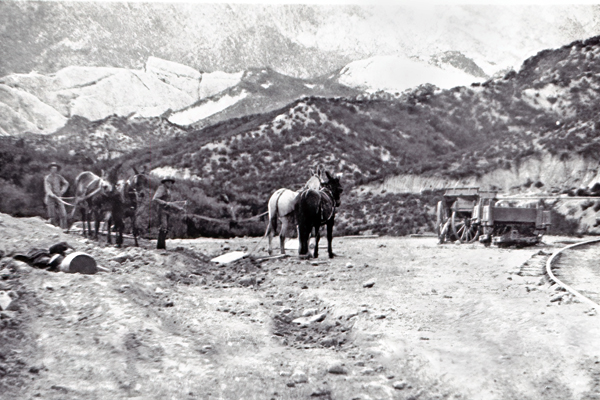

Early Railroad Development: The first railroad to traverse the Cajon Pass was the California Southern Railroad, which was a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF). Construction of this railroad began in the 1880s, with the goal of connecting San Diego with Barstow and the transcontinental rail network. The California Southern Railroad was the first to establish a rail link through the pass.

Competition and Expansion: Other railroads, including the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific, also sought to establish a presence in Southern California. This led to competition and further expansion of rail lines in the region, making the Cajon Pass a vital corridor for the movement of goods and people.

Completion of the Santa Fe Line: The AT&SF completed its line through the Cajon Pass in 1885, providing a direct route from Chicago to the Pacific Coast. This line played a significant role in the development of Southern California and the growth of cities like San Bernardino and Los Angeles.

Rise of San Bernardino: The city of San Bernardino, located at the western end of the Cajon Pass, became a major railroad hub and grew in importance as a transportation center. The city’s rail yards and facilities played a crucial role in the movement of goods and the transfer of passengers.

Engineering Challenges: Constructing and maintaining rail lines through the rugged terrain of the Cajon Pass presented numerous engineering challenges. Building tunnels, bridges, and track beds on steep slopes and rocky terrain required significant effort and ingenuity.

Decline of Passenger Rail: With the rise of automobiles and highways in the mid-20th century, passenger rail service declined. However, freight traffic through the Cajon Pass remained robust and continues to be a critical part of the nation’s transportation network.

Modern Rail Transportation: Today, the Cajon Pass remains a key transportation corridor for freight rail, with multiple rail lines running through it. The BNSF Railway (successor to the AT&SF) and Union Pacific are among the major railroads operating in the pass.

The history of railroads in the Cajon Pass reflects the broader history of American westward expansion and the role of railroads in opening up new territories, fostering economic growth, and shaping the development of cities and regions. The legacy of the railroads in the Cajon Pass continues to be felt in the transportation and economic networks of Southern California and the United States.

Historic Trails and Highways

The Cajon Pass has been historically significant as a transportation corridor. It has been traversed by several historic trails and highways that played crucial roles in the westward expansion of the United States and the development of Southern California. Here are some of the notable historic trails and highways that passed through or near the Cajon Pass:

Old Spanish Trail: The Old Spanish Trail was a historic trade route that connected Santa Fe, New Mexico, to California. It passed through the Cajon Pass, making it an important part of the trail network that facilitated trade between the Spanish colonies of the Southwest and California during the early 19th century.

Mojave Road: The Mojave Road, also known as the Old Government Road, was a 19th-century wagon route that crossed the Mojave Desert. It passed through the Cajon Pass and served as an important east-west transportation route for settlers, traders, and the U.S. military.

Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail: The Mormon Pioneer Trail followed the path of Mormon pioneers who journeyed from the Midwest to the Salt Lake Valley in Utah during the mid-19th century. This trail intersected with the Mojave Road, which passed through the Cajon Pass, as Mormons traveled to California for trade and other purposes.

Santa Fe Trail: While the primary route of the Santa Fe Trail led to Santa Fe, New Mexico, it had several branches and alternative paths. The route connecting California to the Santa Fe Trail passed through the Cajon Pass and the San Bernardino Valley.

California Trail: The California Trail was a major emigrant trail used during the California Gold Rush in the mid-19th century. Many gold seekers and settlers traveling to California passed through the Cajon Pass on their way to the goldfields in Northern California.

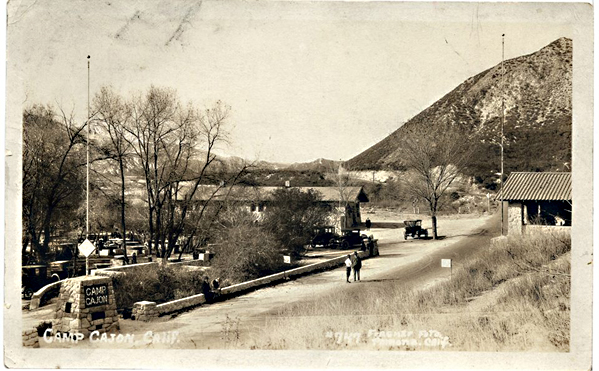

National Old Trails Road: The National Old Trails Road was a transcontinental highway that passed through the Cajon Pass. It was established in the early 20th century and played a role in developing the American highway system.

U.S. Route 66: U.S. Route 66, often referred to as the “Main Street of America,” was a historic highway that connected Chicago to Los Angeles. It passed through the Cajon Pass, and its association with the pass contributed to the highway’s iconic status.

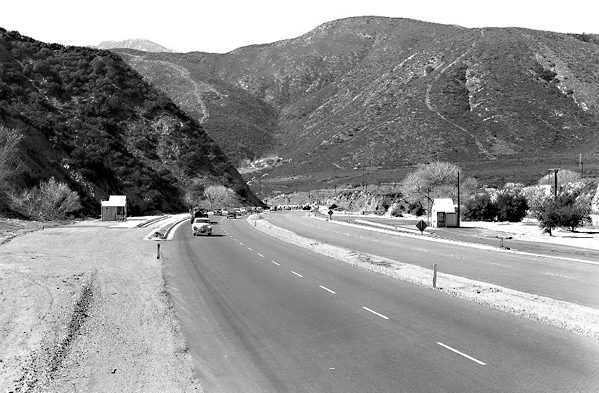

Interstate 15: Modern Interstate 15, which runs through the Cajon Pass, connects Southern California to Las Vegas and points north. It has become a vital part of the national highway system, carrying passenger and freight traffic.

These historic trails and highways were instrumental in opening up the American West, facilitating trade, settlement, and travel, and connecting various regions of the United States. The Cajon Pass’s strategic location as a natural transportation corridor made it a pivotal point on many of these routes, and its historical significance remains evident in the region’s cultural and transportation heritage.

Cajon Pass Geography

The Cajon Pass is a geological and geographical feature located in Southern California, United States. It is a mountain pass in the San Bernardino Mountains, which are part of the Transverse Ranges. The pass is situated approximately 60 miles (97 kilometers) east of Los Angeles and serves as a vital transportation corridor in the region. Here are some key aspects of the geography of the Cajon Pass:

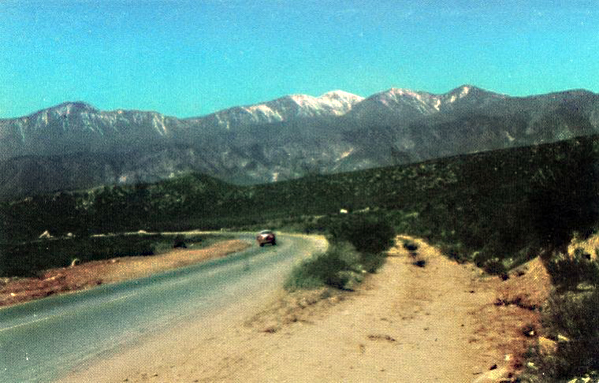

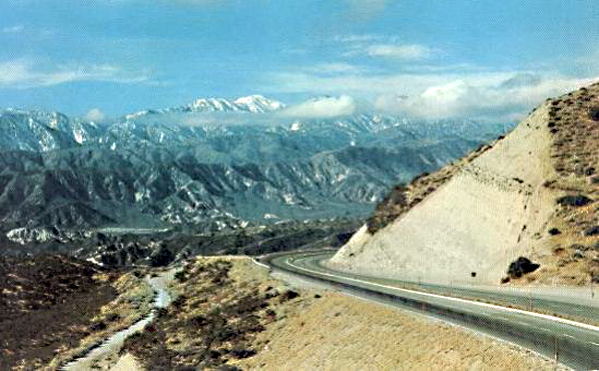

Elevation: The Cajon Pass rises to an elevation of approximately 3,800 feet (1,160 meters) above sea level. This elevation change is significant, and it makes the pass a crucial point in the geography of the region. The pass transitions between the lowland areas to the west and the High Desert region to the east.

Location: The Cajon Pass is located in San Bernardino County, California, and it provides a natural passage through the San Bernardino Mountains, which are part of the larger Transverse Ranges mountain system.

Transportation Corridor: The pass is a critical transportation corridor, facilitating the movement of both passengers and goods. It is part of Interstate 15, which connects the cities of San Bernardino and Victorville in the south to the High Desert region and Las Vegas, Nevada, in the north. Several major highways and rail lines traverse the pass, making it a key component of the region’s transportation infrastructure.

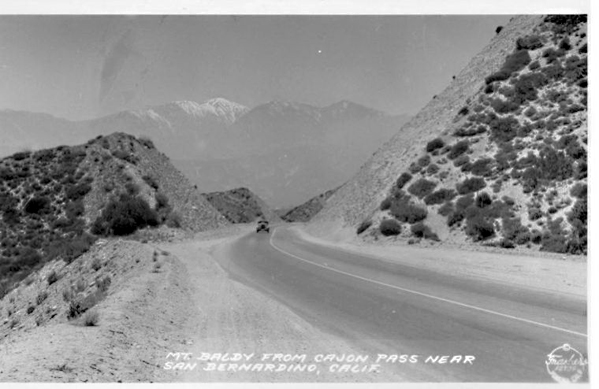

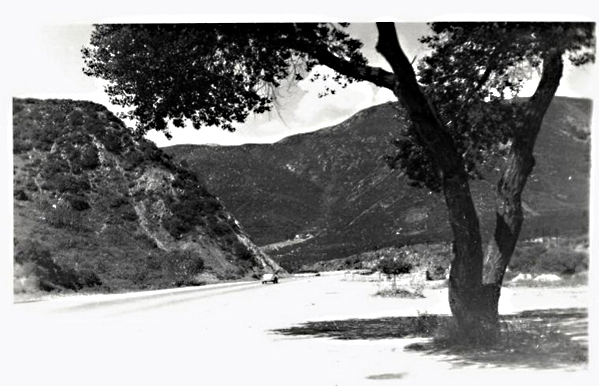

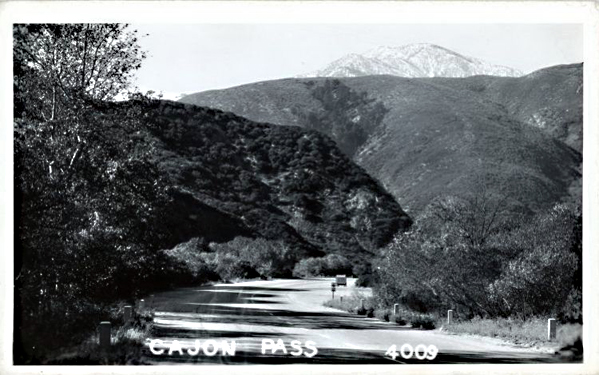

Rugged Terrain: The Cajon Pass is known for its rugged terrain, including steep slopes, rocky cliffs, and canyons. The geology of the pass is influenced by the presence of the San Andreas Fault, which has caused the uplift and displacement of rocks in the area.

Natural Scenery: The pass offers stunning natural scenery, with panoramic views of the surrounding landscape. The rugged topography and diverse plant life in the region make it a popular spot for outdoor enthusiasts, hikers, and nature lovers.

Climate: The climate in the Cajon Pass can vary significantly with the seasons. It experiences hot summers and cold winters, and snowfall is not uncommon during the winter months. The geography of the pass, with its elevation changes, can lead to variations in weather conditions.

Waterways: The pass is intersected by various small streams and watercourses that drain into the Mojave River. These waterways have played a role in shaping the geography of the pass over time.

Wildlife: The region surrounding the Cajon Pass is home to various wildlife, including desert bighorn sheep, often seen in the area.

The Cajon Pass’s unique geography, with its elevation change, rugged terrain, and proximity to the San Andreas Fault, has made it a focal point for transportation and a picturesque destination for those seeking to explore the natural beauty of the San Bernardino Mountains and the surrounding areas in Southern California.

Natural Scenery

The natural scenery around the Cajon Pass is known for its rugged beauty, diverse landscapes, and stunning vistas. This region in Southern California offers a range of natural features and outdoor recreational opportunities. Here are some of the key elements of the natural scenery in and around the Cajon Pass:

Rugged Mountains: The Cajon Pass is surrounded by the San Bernardino Mountains, a rugged and picturesque range of mountains. These mountains consist of various types of bedrock, including schist, gneiss, and granite, which geological forces have shaped over time.

Rocky Cliffs and Slopes: The pass is characterized by rocky cliffs and steep slopes that have been shaped by erosion and tectonic activity. These geological features provide a dramatic backdrop for the pass.

Canyons and Gorges: The region features numerous canyons and gorges, which are often formed by the flow of water. These canyons add to the diversity of the landscape and provide opportunities for exploration and hiking.

Desert Flora: As you move farther east from the pass, you’ll enter the High Desert region of Southern California, characterized by a unique desert ecosystem. Joshua trees, yuccas, creosote bushes, and other desert plants are common in this area.

Mountain Flora: At higher elevations in the San Bernardino Mountains, you’ll find a different array of plant life, including coniferous trees such as pine and fir, as well as a variety of wildflowers that bloom in the spring.

Wildlife: The region is home to diverse wildlife, including desert bighorn sheep, coyotes, bobcats, and numerous bird species. The San Bernardino Mountains and the surrounding High Desert provide habitats for various animal species.

Geological Formations: The presence of the San Andreas Fault and the associated geological activity in the region has led to unique geological formations. These formations include fault lines, exposed rock layers, and uplifted terrain, which interest geologists and nature enthusiasts.

Panoramic Views: The Cajon Pass offers panoramic views of the surrounding landscape. Whether you’re driving along the highways or hiking in the area, you’ll have opportunities to enjoy breathtaking vistas of the San Bernardino Mountains and the High Desert.

Outdoor Activities: The diverse natural scenery in the region provides opportunities for outdoor activities such as hiking, rock climbing, birdwatching, and wildlife photography. The pass is a popular destination for outdoor enthusiasts.

Seasonal Changes: The scenery in the Cajon Pass changes with the seasons. Spring brings wildflower blooms, while the winter months can see snow on the mountains. Each season offers a unique and beautiful perspective on the landscape.

The natural scenery in and around the Cajon Pass is a testament to the diverse and dynamic landscapes found in Southern California. It offers various outdoor experiences for those who appreciate the beauty of the region’s geography and the opportunity to explore its natural wonders.