Inyo Canyon, Death Valley National Park

The Needle’s Eye is a narrow rock portal in the upper section of Inyo Canyon on the west side of the Funeral Mountains. It sits in a remote tributary draining toward the lower end of Death Valley. The feature is a natural window carved into steep canyon walls where erosion exploited weaker zones in the bedrock, leaving a tight, vertical opening that frames the sky from the canyon floor. The canyon itself is a classic debris-cut gash through Paleozoic formations associated with the Inyo Mountains and the Cottonwood block uplift.

Travel to the Needle’s Eye follows old miner and prospector routes up Inyo Canyon toward workings scattered along the western flank of the range. The canyon exhibits evidence of washouts, slumping, and boulder chutes, which were produced by cloudbursts and winter runoff. Side slopes exhibit talus fans and dryfalls that mark intervals of rapid erosion. The rock types shift from limestone and dolomite to more resistant quartzites in the upper reaches, with the Needle’s Eye forming at a contact of contrasting hardness.

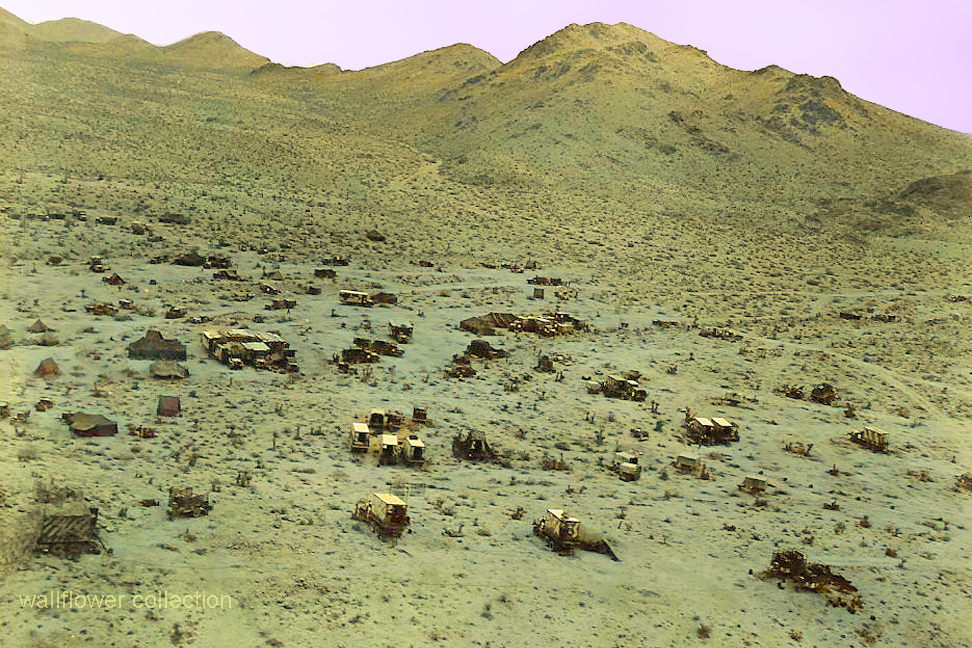

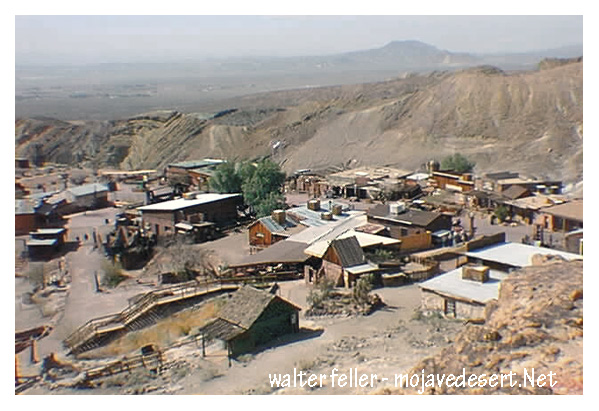

Human activity in Inyo Canyon dates back to early prospecting waves in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Small diggings, adits, and tent camps once dotted the margins of the canyon. Miners used the route as an access path while searching for lead, silver, and other minerals typical of the Cottonwood and Inyo belts. No permanent settlement survived the lack of water, rugged terrain, and unreliable ore bodies. Occasional surveyors and desert wanderers later described the canyon’s narrow rock door as a striking landmark.

The Needle’s Eye fits naturally into the region’s long tradition of desert travel through constrained bedrock points. It shares similar features with those found elsewhere in the Mojave, where travelers have passed through tight clefts or rock windows while following natural drainages. The spot also marks a transition between lower alluvial slopes and the more rugged upper canyon, giving it prominence on foot routes. Today, it offers a quiet reminder of past use and the steady work of water and gravity shaping the canyon.

References

Burchfiel, B. C., and Davis, G. A. 1981. Mojave Desert and Inyo Mountains tectonic studies. Geological Society of America Bulletin.

Hunt, C. B. 1975. Death Valley: Geology, Ecology, Archaeology. University of California Press.

McAllister, J. F. 1956. Geology of the Furnace Creek Quadrangle, Death Valley, California. USGS Professional Paper 354.

Nolan, T. B. 1928. Geology of the Inyo Range and the White Mountains. University of Nevada Bulletin.

Storz, J. 1970s. Desert Magazine articles on Death Valley side canyons and miner routes.

Wright, L. A., et al. 1974. Geology of the Death Valley region. California Division of Mines and Geology Special Report series.

USGS. 1988. Geologic Map of the Death Valley Region, California and Nevada. Miscellaneous Investigations Map I-1933.

NPS. Death Valley National Park Backcountry and Wilderness Access Guides (Inyo Canyon section).

NPS. 1994–present. Death Valley National Park administrative files on backcountry routes and cultural resource surveys.

Stovall, H. 1930s–1940s. Notes of prospecting and travel in the Inyo and Cottonwood Mountains (archival field notebooks cited in regional mining histories).