Geological and Environmental Background

Pleistocene Era (circa 2.5 million years ago) The origins of Rogers Dry Lake, located in the Antelope Valley within the Mojave Desert, trace back to the Pleistocene Era, around 2.5 million years ago. As a pluvial lake, it boasts an incredibly flat, smooth, and hard surface, which can withstand pressures up to 250 psi. These unique geological characteristics made Rogers Dry Lake a natural choice for aviation and automotive speed trials. Covering approximately 65 square miles, the lakebed forms a rough figure eight and is known for its harsh climate, experiencing extreme temperatures, violent dust storms, and mesmerizing sunsets.

Early Settlement and Development

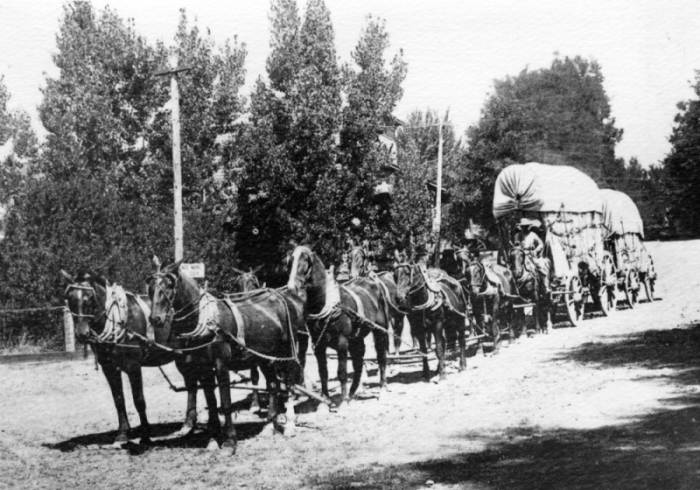

Pre-1876: Sparse Population and Railroad Expansion Before significant settlement, the area was primarily inhabited by occasional prospectors searching for mineral wealth. The Southern Pacific Railroad established a water stop near the lakebed in 1876. In 1882, the Santa Fe Railroad extended westward from Barstow toward Mojave, establishing another water stop at the edge of what was then called Rodriguez Dry Lake. By the early 1900s, the name “Rodriguez” had been anglicized to “Rogers.”

1910: The Corum Family and the Founding of Muroc In 1910, the Corum family settled at the lakebed, naming the area “Muroc” by reversing their last name after their original choice, “Corum,” was rejected due to its similarity to “Coram, California.” The Corum family established a general store and post office, attracting other homesteaders and helping to develop the area. Their efforts laid the foundation for what would become a significant site in both aviation and automotive history.

Early Racing Events

1920s: The Dawn of Speed Events Muroc Dry Lake became a prominent site for American Automobile Association (AAA) sanctioned speed events during the 1920s. The affordability and modifiability of the Model T made it the preferred vehicle for early hot rodders. Roadsters were favored among racers, but touring cars were also frequently raced. In May 1923, Joe Nikrent set a speed record of 108.24 miles per hour in a stripped-down Buick. The following year, Tommy Milton achieved 151.26 mph in a Miller-powered race car. In 1927, Frank Lockhart reached a speed of 171 miles per hour, further cementing Muroc’s reputation as a premier racing venue.

October 9, 1927: Southern California Champion Sweepstakes One of the most significant early racing events was the Southern California Champion Sweepstakes, held on October 9, 1927. Organized by Earl Mansell from Pasadena, California, the event featured five classes of competition:

- Ford Roadsters: Open to any Ford roadster with or without fenders or windshields, requiring a hood and turtle deck.

- Ford Coupes: Required fenders, hood, windshield, and doors.

- Ford Touring Cars: Fenders and windshields were optional.

- Special Flathead Race: Open to any body style with a flathead engine, offering refunded entry fees to winners of the previous events.

- Championship Sweepstakes: Open to any roadster, coupe, or touring car, with the option to race without windshield or fenders.

Organized Racing and the SCTA

1931: The First Organized Speed Trials In 1931, one of the first known organized amateur speed trials took place at Muroc, sponsored by Gilmore Oil Company of Los Angeles and organized by George Wight, owner of Bell Auto Parts. Recognizing the need for coordinated rules and regulations, Wight invited hot rodders to an organizational meeting in East Los Angeles. Early rules categorized cars based on engine types, including Model T flatheads, Model T Rajos, Model T Frontenacs and Chevrolets, Model A flatheads, and Model A overhead valve conversions. Supercharged cars were not allowed to compete. The first organized meet was held on March 25, 1931, followed by another on April 19, 1931. Safety measures were implemented, such as a 40 mph speed limit for returning cars and penalties for jumping the start.

Formation of the Muroc Racing Association By the end of 1931, the Muroc Racing Association was formed, complete with officers and a race program. The association collected a one-dollar entry fee to cover expenses, and the Purdy Brothers developed an electrical timer to clock the cars’ speeds, further formalizing the events.

1932-1933: Changes in Classification In 1932, the trials continued under the same rules, but significant changes in car classification were introduced. Cars were now categorized as either stock-bodied or modified. Stock-bodied cars could have certain parts removed, while modified cars were significantly altered. Between the 1932 and 1933 seasons, classifications shifted to speed and body type, with new classes based on potential top speeds. This change aimed to ensure fairness and safety, with measures like painting speedometers with white shoe polish to prevent drivers from knowing their exact speed.

Military Establishment and World War II

September 1933: The Arrival of the Army In 1933, the United States Army arrived at Muroc, recognizing the lakebed’s potential as an airfield. The Muroc Bombing and Gunnery Range was established, and by 1937, the United States Army Air Corps set up Muroc Air Field for training and testing purposes.

World War II and the Establishment of Muroc Army Air Base During World War II, Muroc Army Air Base was activated, serving as a major training site for bomber crews and fighter pilots. The flat, hard surface of Rogers Dry Lake was ideal for aircraft testing, including early jet planes like the Bell XP-59A and the Lockheed XP-80. On October 1, 1942, the Bell XP-59A Airacomet, America’s first jet plane, made its first flight at Muroc. The base played a crucial role in the war effort, training crews and testing new aircraft.

Post-War Developments After the war, Muroc continued to be a central hub for aviation research and development. The Bell X-1, piloted by Capt. Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager, broke the sound barrier on October 14, 1947, marking a significant milestone in aviation history. The base was renamed Edwards Air Force Base in February 1948 in honor of Capt. Glen W. Edwards, who died in a test flight accident. By 1950, Edwards Air Force Base was officially dedicated and recognized as the U.S. Air Force Flight Test Center (AFFTC).

The Hot Rodding Era

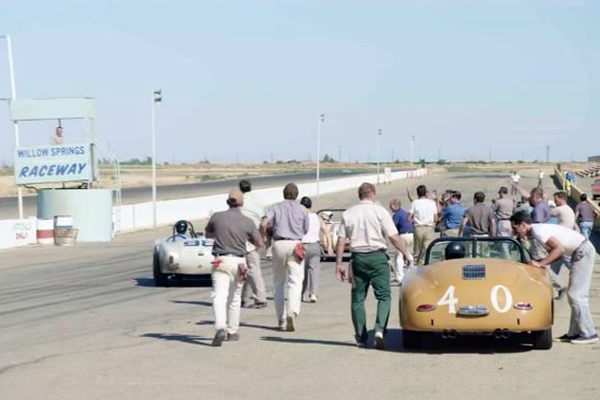

Post-War Racing and El Mirage The end of World War II marked a transition from racing activities at Muroc to El Mirage, another dry lakebed south of the air base. While El Mirage was not as ideal as Muroc, it continued to host hot rodding events. The SCTA (Southern California Timing Association) organized several “reunion” races at Muroc in 1995, bringing together a generation of racers who had participated in early SCTA events. However, racing activities at Muroc were halted following the events of September 11, 2001, due to security concerns.

Legacy and Continued Significance

Aviation and Hot Rodding Heritage Muroc’s dual legacy as a pioneering site for both aviation and hot rodding remains significant. Edwards Air Force Base continues to be a premier flight testing center, contributing to numerous advancements in aerospace technology. Meanwhile, the early days of hot rodding at Muroc are fondly remembered by enthusiasts and are considered a foundational period in the history of American motorsports.

Current Status and Future Prospects While racing activities at Muroc have ceased, El Mirage remains an active site for hot rodding events. The SCTA continues to organize races, preserving the spirit and tradition of early speed trials. There is hope that, in the future, Muroc might once again host racing events, allowing the sands to echo with the sounds of high-speed automotive competition.

In conclusion, Muroc’s history is a testament to its unique geographical features and its adaptability, serving as a critical site for both military aviation and automotive racing. The integration of these diverse historical elements highlights Muroc’s significant contribution to American technological and cultural heritage.