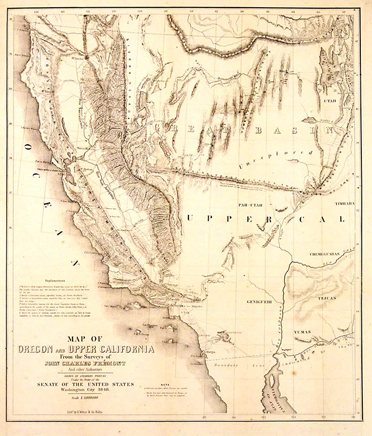

A) The Mojave River spine (Colorado River → eastern Mojave springs → Mojave River corridor → Cajon Pass → San Bernardino/LA)

Mojave Indian Trail; Mojave River Trail; Mojave Road; Old Spanish Trail (where it drops into/uses Mojave River and related desert crossings); Beale’s Wagon Road (in its CA desert segment); Brown’s Toll Road (as the Cajon gateway upgrade); plus the generic “Wagon Roads” label when you’re talking about the 19th-century wagonable evolution of the same line.

The idea is simple: reliable water spacing and a workable pass dictated the alignment. The Mohave Trail conceptually underlies the later Mojave Road, and the NPS explicitly treats the Mojave Road through Mojave National Preserve as a branch of the Old Spanish National Historic Trail. Beale’s route description also ties his Mojave Desert segment to the Mojave Trail/Old Spanish Trail network, then notes the junction with the Mormon Road at the Mojave River. Brown’s Toll Road is best understood as “the Cajon Pass switch” that made the desert–coast connection more serviceable (toll/improvement era), not a whole new long-distance corridor by itself.

B) The LA ↔ Salt Lake “southern route” family (good-roads era branding laid over older travel)

Salt Lake Road; Old Spanish Trail (northern route pieces); Arrowhead Trails Highway; and again “Wagon Roads” as the pre-auto baseline.

This is the family that turns into the famous LA–Las Vegas–Salt Lake motor corridor in the auto-trails era. The BLM’s Arrowhead Trails Highway page is blunt about the lineage: the proposed/marketed auto route followed the late-19th-century “Old Mormon Road” and the earlier Old Spanish Trail. The Arrowhead Trail’s “association/branding layer” starts in 1916 (organized/incorporated that year) and is essentially a named-trail wrapper on that corridor.

C) “Good Roads” transcontinental overlays (names that often ride on top of existing roads, then feed into numbered highways)

National Old Trails; Midland Trail; Route 66 (as the numbered successor in the Southwest); and sometimes Arrowhead Trails Highway where it shares pavement with the NOTR in Southern California.

The key point: these aren’t necessarily new alignments end-to-end; they’re promotional/organizational systems that sign and improve what counties and states already had. FHWA and other summaries describe the National Old Trails Road Association as one of the early major named-trail movements (founded 1912). In the West, big stretches of the NOTR were later folded into US 66, which was established/commissioned in 1926 (signing followed). The Midland Trail is another early signed transcontinental auto trail (signed by 1913) that overlaps conceptually with the named-trails era rather than replacing everything on the ground.

D) The Sierra/Eastern Sierra north–south family (LA ↔ Mojave ↔ Owens Valley and beyond)

Sierra Highway / El Camino Sierra.

This one is its own long corridor family, and it intersects the desert east–west systems at junction towns rather than duplicating them. It’s commonly framed as an early 20th-century promoted route (established/advertised early, with later highway rebuilds) connecting Los Angeles into the Eastern Sierra.

E) The Tejon/Tehachapi gateway family (LA Basin ↔ San Joaquin Valley crossings)

Fort Tejon Road; Ridge Route.

Think “northbound exit from the LA Basin” rather than “Mojave crossing.” The Los Angeles–Fort Tejon Road is described as a successful wagon road solution over/near the Tehachapi barrier, completed in 1855. The Ridge Route is the early engineered state highway-era answer (opened 1915) that finally made that link paved and direct in the automobile age.

F) San Bernardino/San Gabriel mountain connectors (coast ↔ mountain communities, not trans-desert corridors)

Rim of the World Drive; Angeles Crest Scenic Drive (Angeles Crest Highway); Van Dusen Road.

These are “mountain access projects” more than “interregional desert crossings.” Rim of the World Drive is documented as opening in 1915 to connect San Bernardino with Big Bear through the range. Angeles Crest Highway construction begins in 1929 and the completed through-route opens much later (mid-20th century). Van Dusen Road sits here as an earlier wagon-road era Big Bear/Holcomb access line tied to the 1860–61 gold rush logistics (often described as a wagon road built in 1861).

G) Death Valley–Panamint access network (mining roads, toll-road tourism era, park-era backroads)

West Side Road (Death Valley); Road to Panamint; Eichbaum’s Toll Road (same as “Eichbaum Toll Road”).

This family is its own ecosystem: borax-era freight roads, mining camp supply lines, then purpose-built access to resorts/tourism. NPS frames the borax era as transport over “primitive roads” (1883–1889). The Eichbaum Toll Road is well-documented as a 1925–26 build from near Darwin to Stovepipe Wells (i.e., a deliberate west-side entry improvement). “Road to Panamint” is best treated as the umbrella for the Panamint Valley/Skidoo/Rhyolite road-pushing phase in the 1906–1907 window and its successors; NPS history material and HAER/other documentation talk explicitly about wagon-road development and the Rhyolite–Skidoo road beginning in 1906 and being in use by 1907. West Side Road is the park backroad line on the valley floor’s west side (modern status aside), squarely in the “Death Valley internal access” bucket.