A learning tool

All right, here’s the whole story. No jargon, no technical formatting, just the history of how Lauren Wright and Bennie Troxel shaped our understanding of Death Valley, Tecopa, and the southern Mojave region.

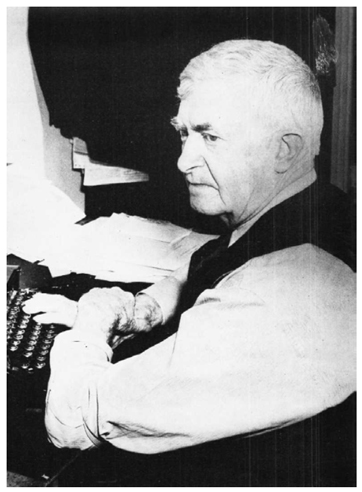

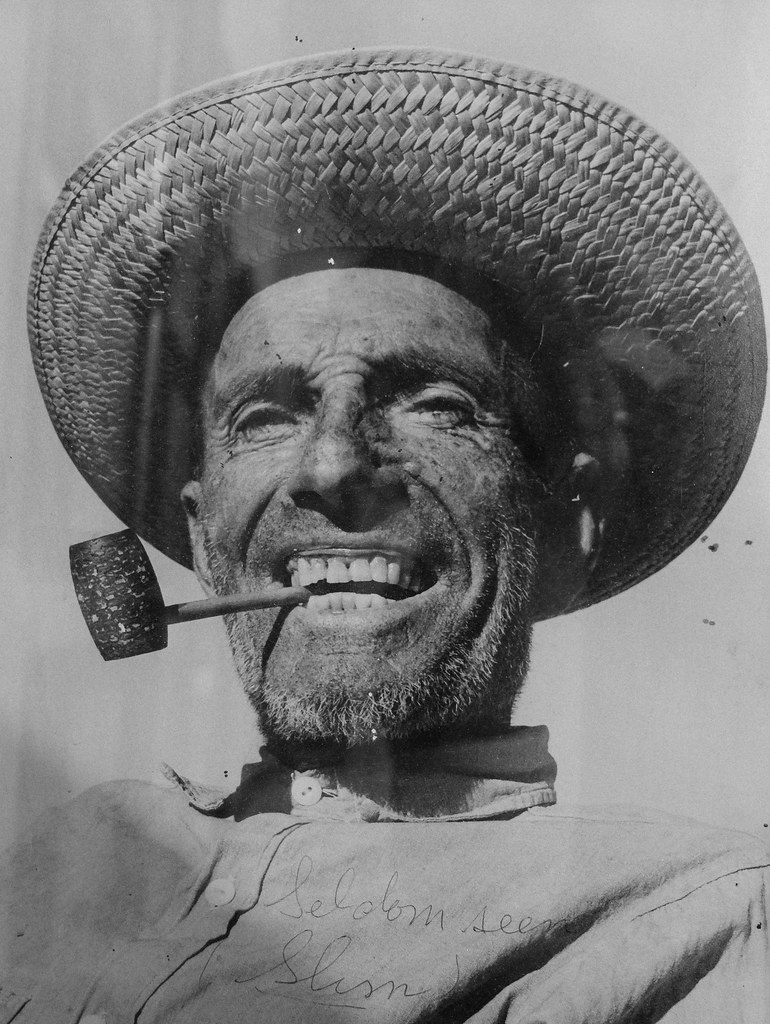

Lauren Wright and Bennie Troxel spent their lives in the desert. Starting in the early 1950s, they mapped the roughest country in Death Valley and beyond. What others called chaos, they patiently untangled, rock by rock. Over the years they became two of the most trusted voices in Basin and Range geology, known for their steady field habits, clean maps, and deep respect for what the land itself could tell them.

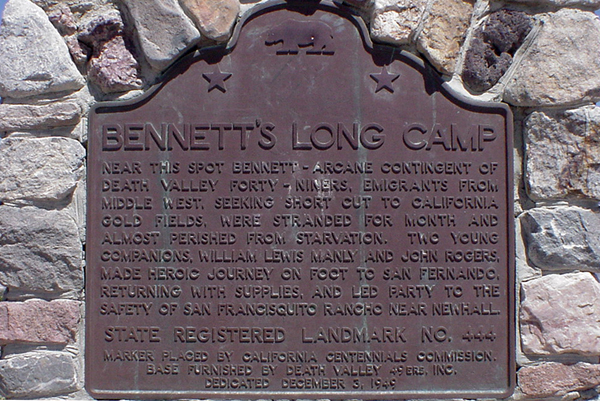

They began in Death Valley, working through the twisted terrain east of Badwater and Furnace Creek. There, scattered fault blocks looked like a puzzle someone had shaken apart. Wright and Troxel figured out that this “Amargosa Chaos” wasn’t random at all. It was the result of the crust stretching and tearing at low angles, lifting old rocks and dropping young ones. Their maps from the 1960s and 70s showed that the Valley wasn’t just a crack in the earth, but part of a much larger system in which the crust itself was thinning.

They studied the Furnace Creek and Death Valley fault zones and showed that the sideways, or strike-slip, motion wasn’t as massive as some believed. The land was moving both sideways and downward — sliding, stretching, and rotating all at once. Their careful work stopped wild speculation and grounded future studies in what could actually be seen in the rocks.

Later, when the field began to recognize “detachment faults” — those broad, low-angle breaks deep in the crust — Wright and Troxel were already there. They had mapped them years before anyone had a name for them. Their diagrams of tilted mountain blocks, uplifted footwalls, and sinking basins became the foundation for how geologists now picture the Basin and Range province.

Their influence spread southward, into the Tecopa and Shoshone area. Tecopa Basin, once thought of as just a dried-up lake, became under their framework a living tectonic basin — a place still moving, still changing. The basin sits between the Resting Spring Range on the east and the Nopah Range on the west, both tilted blocks bounded by faults. Wright and Troxel’s regional mapping explained how those ranges rose and the basin sank, all part of the same crustal stretching that shaped Death Valley.

The Resting Spring Range, they showed, is a footwall block lifted on a west-dipping detachment fault. That fault likely channels the hot water that feeds Tecopa’s springs. Across the basin, the Nopah Range tilts the other way, dropping the valley floor between them. The lake beds and alluvial fans that fill the basin record every stage of that movement. Their approach — always linking sediments, structure, and landscape — became the standard way of reading desert basins.

Following their line of thought south, the fault belt continues through Sperry Wash to the Kingston Range. There the crust was pulled so thin that deep rocks rose to the surface. Later researchers would prove the Kingston Range to be a metamorphic core complex, but it was Wright and Troxel’s earlier insight into Death Valley’s structure that pointed the way. They showed that the same forces that opened Death Valley also lifted the Kingston Range and dropped the Tecopa Basin between them.

At the southern edge of this chain lies the Avawatz Mountains, a natural hinge between the stretching Basin and Range and the sliding Mojave block. Wright and Troxel understood this as the turning point — where extension gives way to sideways shear. The Garlock Fault lies just to the south, a great east-west fracture that shifts motion from one style to another. They were among the first to argue that these systems are connected, not separate. The Garlock doesn’t stop Death Valley; it redirects it.

South of the Avawatz, the story continues through Soda and Silver Lakes, the broad dry basins near Baker. These, too, line up along the same fault trend. The Mojave River, flowing northward from the mountains through Barstow, traces that same old scar in the crust. The river’s course isn’t random — it follows a tectonic path carved long before any water ran through it. Every terrace, canyon, and dry lake along its route echoes the same pattern Wright and Troxel mapped farther north.

By the time the river reaches Afton Canyon and the dry sinks of Cronese and Soda Lake, it’s running through the tail end of their structural corridor. The ground here still moves, slowly and quietly, along the Lenwood, Lockhart, and Helendale faults. These smaller strands pick up the motion of the Garlock and pass it westward toward the San Andreas. The Mojave River flows right through the middle of it all — a living reminder of how deep-seated tectonics shape even the surface flow of water.

Wright and Troxel’s gift was not just their data but their way of seeing. They treated the desert as a single, connected organism — every basin, every fault, every dry lake part of the same long rhythm of motion. Where others saw disjointed ranges, they saw a story of continuous transformation, stretching from Furnace Creek to Barstow and beyond.

Their maps still hang in field camps and classrooms, and the Geological Society of America’s Wright–Troxel Award continues to support students studying these same basins. The accuracy of modern GPS and seismic work has only confirmed what they drew by hand half a century ago.

In the end, their legacy is both scientific and human. They showed that patient fieldwork, careful observation, and respect for the land can turn confusion into clarity. Thanks to them, the Mojave and Death Valley are no longer a tangle of broken hills but a single, coherent landscape — one long story written in the language of stone.