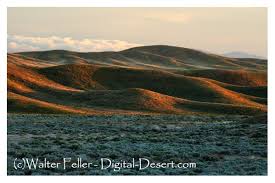

What would it have been like to live on the edge of the desert wilderness between 1850 and 1970?

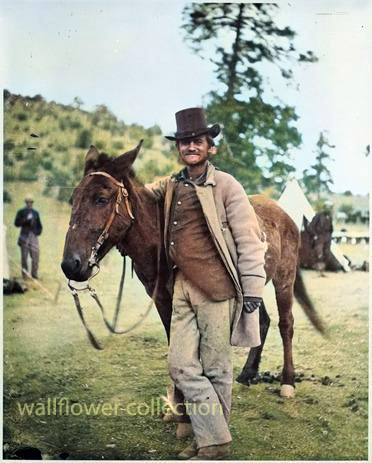

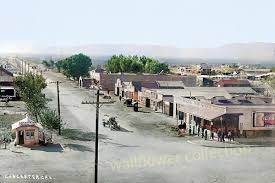

Life in the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico area between 1850 and 1870 would have been characterized by the challenges and opportunities of frontier living and the influence of the California Gold Rush.

During this period, the area was an important outpost along the Mojave Road, a major trade route connecting southern California with the rest of the Southwest. Barstow, Daggett, and Calico towns would have seen a steady stream of pioneers, settlers, and traders passing through, seeking respite, supplies, and companionship on their journeys.

Life in the area would have been challenging, as settlers and travelers had to contend with harsh desert conditions, extreme temperatures, and limited resources. The towns would have offered essential services—food, water, lodging, and blacksmithing —providing a lifeline for those passing through the unforgiving landscape.

The California Gold Rush of the late 1840s and 1850s also affected the area, as prospectors and miners flocked to California in search of their fortunes. The discovery of gold and other minerals in the region attracted settlers and entrepreneurs, leading to mining camps and boomtowns.

Life in the mining camps and towns would have been marked by hard work, uncertainty, and camaraderie as people came together to build communities and seek their fortunes in the California desert. The mining industry played a central role in shaping the area’s economy and society, with miners facing dangerous working conditions and fluctuations in the market for minerals.

Overall, life in the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico area between 1850 and 1870 would have been characterized by the challenges and opportunities of frontier living. The towns served as vital outposts, providing essential services and support to pioneers and settlers seeking a better life in the American West.

1871 – 1900

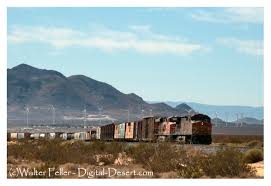

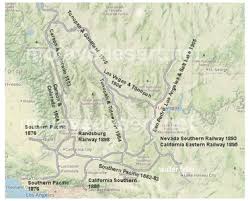

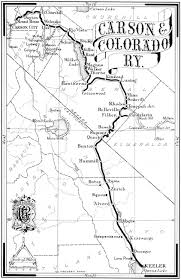

The introduction of the railroad to the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico area between 1871 and 1900 would have significantly impacted the region’s life and economy.

The railroad would have facilitated the transportation of goods, materials, and people to and from the mining towns, making it easier to access the area and transport resources in and out. This would have boosted the local economy and helped the mining industry thrive by providing a more efficient means of transportation for the minerals extracted from the mines.

The railroad also brought an influx of new settlers and businesses to the area, further contributing to the growth and development of the towns. The increased connectivity provided by the railroad would have helped the communities in the area become more integrated with the rest of the region and the broader economy.

Life in the mining towns between 1871 and 1900, with the presence of the railroad, would have been marked by increased economic activity, improved infrastructure, and enhanced opportunities for trade and commerce. The towns would have become more connected to the outside world, allowing for exchanging goods, services, and ideas.

The railroad would have also influenced social life in the towns, bringing new cultural influences and experiences to the area. The increased mobility provided by the railroad would have allowed for more interaction between the residents of the mining towns and the wider world, enhancing the diversity and vibrancy of the communities.

Overall, the introduction of the railroad to the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico area between 1871 and 1900 would have been a transformative event, shaping the region’s economy, society, and culture and contributing to the growth and prosperity of the mining towns during this period.

1901 – 1926

Life in the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico areas between 1901 and 1926 would have been influenced by the region’s continued growth and development, as well as by significant historical events and social changes during that time.

- Railroad Expansion: The early 20th century saw further expansion of the railroad network in the area, with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway playing a prominent role. The railroads continued to be a driving force in the local economy, facilitating the transportation of goods, people, and resources to and from the towns.

- Mining Industry: The mining industry remained a significant part of the economy during this period, with Calico continuing to produce silver, borax, and other minerals. The town experienced periods of boom and bust as the demand for minerals fluctuated, shaping the livelihoods of the residents in the area.

- Cultural and Social Changes: The early 20th century brought about changes in cultural and social norms, with new technologies, entertainment, and modes of transportation becoming more prevalent in the region. The towns would have been influenced by trends in popular culture and the influx of new residents and visitors to the area.

- World War I: The impact of World War I would have been felt in the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico areas, with residents likely affected by the war effort, rationing, and economic changes resulting from the conflict. The mining industry may have seen shifts in production and demand during this time.

- Prohibition and the Roaring Twenties: The period also saw the implementation of Prohibition in the United States, which may have had varying effects on the towns depending on their adherence to the ban on alcohol. The Roaring Twenties brought about changes in social customs, fashion, and entertainment that would have been reflected in the area’s communities.

Overall, life in the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico areas between 1901 and 1926 would have been a dynamic mix of economic, social, and cultural changes shaped by the continued growth of the region, historical events, and the evolving lifestyles of the people living in the American Southwest during this time.

1927 – 1940

Significant changes in transportation, economic conditions, and social dynamics shaped life in the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico areas between 1926 and 1940. The introduction of the National Old Trails Highway and later Route 66, followed by the onset of the Great Depression, would have had a profound impact on the communities in the region.

- Route 66 and Transportation: Establishing Route 66 as a major east-west highway in 1926 would have brought increased traffic, travelers, and commerce through the towns of Barstow, Daggett, and Calico. The highway served as a vital link between the Midwest and the West Coast, providing economic opportunities for businesses along its route.

- Impact of the Great Depression: The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 would have brought economic hardship to the area’s residents. The collapse of the economy, widespread unemployment, and financial instability would have affected the towns’ businesses, workers, and families, leading to struggles to make ends meet and maintain their livelihoods.

- Mining Industry and Agriculture: The mining industry in Calico and surrounding areas may have been impacted by the economic downturn, with fluctuations in demand for minerals and challenges in maintaining profitability. Agriculture in the region may have also faced challenges due to the Depression, affecting local farmers and growers.

- Migration and Transient Population: The economic conditions of the Great Depression may have led to an influx of migrants, transient populations, and “Okies” traveling along Route 66 in search of work and opportunities. The towns along the highway would have seen more transient populations passing through, seeking respite and resources.

- Community Support and Resilience: Despite the era’s challenges, the communities in Barstow, Daggett, and Calico would have likely come together to support one another, with local organizations, churches, and charities assisting those in need. Resilience, resourcefulness, and a sense of community would have been key in navigating the difficulties of the Great Depression.

Overall, life in the Barstow, Daggett, and Calico area between 1926 and 1940 would have been characterized by the transformative impact of Route 66, the challenges of the Great Depression, and the resilience of the communities in the face of economic hardship and uncertainty. The towns would have been part of a shifting landscape shaped by changes in transportation, economy, and society during this time period.

1941 – 1970

Life in the Barstow area between 1941 and 1970 would have been marked by significant historical events, economic changes, and social transformations that influenced the development and character of the region during this period. Here are some key aspects of life in the Barstow area between 1941 and 1970:

- World War II and Military Presence: The outbreak of World War II in 1941 would have profoundly impacted the Barstow area, as the town’s strategic location and proximity to military installations made it a hub for military activity. The nearby Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow and the National Training Center at Fort Irwin would have brought a significant military presence to the region, influencing the local economy and community.

- Industrial Development: The post-war period saw the growth of industrial development in the region, driven in part by the construction of highways, such as Interstate 15 and Interstate 40, that passed through the Barstow area. The expansion of transportation infrastructure, including railroads and highways, facilitated the movement of goods and people through the region, contributing to economic growth.

- Population Growth and Urbanization: The period between 1941 and 1970 would have witnessed population growth and urbanization in the Barstow area as more people moved to the region searching for employment opportunities, particularly in the military, transportation, and logistics sectors. The town of Barstow would have experienced changes in its demographics and urban landscape during this time.

- Cultural and Social Changes: The post-war period brought about cultural and social changes in the Barstow area, influenced by trends in popular culture, music, and entertainment. The town would have been impacted by shifts in societal norms, technological advancements, and changing attitudes toward race and gender.

- Civil Rights Movement and Social Activism: The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s would have resonated in the Barstow area as communities grappled with racial inequality, discrimination, and social justice issues. Residents may have participated in civil rights activism, protests, and movements for equality and justice during this period.

- Environmental Concerns: The growth of industrial activity and infrastructure in the Barstow area would have raised ecological concerns related to pollution, resource depletion, and land use. In response to these challenges, residents may have become more aware of the need for environmental conservation and sustainability.

Overall, life in the Barstow area between 1941 and 1970 would have been shaped by wartime mobilization, industrial development, population growth, cultural changes, social activism, and environmental considerations. The region would have been part of a dynamic landscape undergoing transformation and evolution in response to historical events and societal shifts during this time.

1971 – 2000

Living in the Barstow area from 1971 to 2000 would have been characterized by continued growth, industry changes, demographic shifts, and evolving social dynamics. Here are some critical aspects of life in the Barstow area during this period:

- Military Influence: The presence of military bases, such as the Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow and the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, would have continued to shape the economy and community of the Barstow area. Military personnel and their families would have been a significant part of the population, contributing to the local economy and culture.

- Transportation Hub: Barstow’s strategic location at the intersection of major highways, including Interstate 15 and Interstate 40, would have solidified its role as a transportation hub. The town would have continued to serve as a stop for travelers, truckers, and tourists passing through the area on their way to Southern California destinations.

- Industrial and Economic Development: From 1971 to 2000, the Barstow area would have seen further industrial and economic development. The expansion of logistics, transportation, and distribution industries would have created job opportunities and attracted businesses to the region, contributing to local economic growth.

- Tourism and Hospitality: Barstow would have become a popular stopping point for tourists visiting attractions such as the Calico Ghost Town, the Mother Road Museum, and Route 66 landmarks. The hospitality industry, including hotels, restaurants, and retail shops, would have flourished to cater to visitors passing through the area.

- Environmental Awareness and Conservation: The Barstow area may have experienced increasing awareness of environmental issues and a growing emphasis on conservation and sustainability during the 1971 to 2000 period. Efforts to protect natural resources, preserve desert ecosystems, and promote responsible land use would have become more prominent in the community.

- Cultural Diversity and Community Life: The demographic makeup of the Barstow area would have continued to diversify, reflecting immigration, migration, and changes in population trends. Residents would have celebrated cultural diversity through community events, festivals, and activities that showcase different traditions and heritage.

- Technological Advancements: Advances in technology, communication, and digital infrastructure would have influenced daily life in the Barstow area. Residents may have experienced improved connectivity, access to information, and changes in how they interact with technology in their personal and professional lives.

Living in the Barstow area from 1971 to 2000 would have been characterized by a mix of military influence, transportation prominence, economic development, tourism opportunities, environmental awareness, cultural diversity, and technological advancements. The town would have continued to evolve and adapt to changing conditions while maintaining its role as a significant community in the high desert region of Southern California.

2001 – 2021

Life in the Barstow area from 2001 to today would have been characterized by further economic development, changes in industry, continued military presence, technological advancements, and ongoing efforts to address social and environmental issues. Here are some critical aspects of life in the Barstow area during this period:

- Economic Diversification: The Barstow area would have continued to diversify its economy beyond traditional industries such as transportation and military-related sectors. Efforts to attract new businesses, promote tourism, and support local entrepreneurship would have contributed to the region’s economic growth and job creation.

- Renewable Energy Initiatives: The Barstow area may have seen increased focus on renewable energy initiatives, such as solar and wind power projects, as part of efforts to transition towards sustainable energy sources and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. These developments would have created opportunities for green jobs and investment in clean technology.

- Infrastructure Improvements: Infrastructure projects, including upgrades to transportation networks, utilities, and public facilities, would have been implemented to support the growing population and economic activities in the Barstow area. Investments in infrastructure would have aimed to enhance connectivity, efficiency, and quality of life for residents.

- Military Training and Operations: The Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow and the National Training Center at Fort Irwin would have continued to play a significant role in the community, providing training and support for military personnel and contributing to the local economy. Military exercises and operations conducted in the region would have influenced daily life for residents.

- Education and Healthcare Services: Access to education and healthcare services in the Barstow area would have been a focus of community development efforts. Schools, colleges, and medical facilities would have expanded to meet the needs of a growing population and ensure that residents have access to quality services.

- Community Engagement and Social Initiatives: Community organizations, non-profit groups, and local government agencies would have worked together to address social issues, promote inclusivity, and support community well-being. Initiatives related to youth programs, affordable housing, healthcare access, and cultural events would have enriched the social fabric of the Barstow area.

- Digital Connectivity and Innovation: Technological advancements in communication, digital infrastructure, and e-commerce would have influenced how residents in the Barstow area connect, access services, and engage with the broader world. Efforts to expand broadband access and promote digital literacy would increase connectivity and provide opportunities for residents.

Overall, life in the Barstow area from 2001 to today would have been shaped by ongoing economic development, infrastructure improvements, renewable energy initiatives, military activities, community engagement, technological advancements, and efforts to address social and environmental challenges. The region would have continued to evolve and adapt to changing conditions while maintaining its unique character and sense of community in the high desert of Southern California.