Don Antonio Maria Lugo, of Los Angeles, was genial and witty, about eighty years of age, yet active and elastic, sitting on his horse as straight as an arrow, with his reata on the saddle, and as skillful in its use as any of his vaqueros. He was an eccentric old gentleman. He had a wife aged twenty or twenty-two—his third or fourth. In 1846 I visited him. After cordially welcoming me, he introduced me to his wife, and in the same breath, and as I shook hands with her, said, in a joking way, with a cunning smile, “ No se enamore de mi joven esposa.” (Don’t fall in love with my young wife.) He had numbers of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Los Angeles was largely populated from his family. Referring to this circumstance, he said to me, quietly, “ Don Guillermo, yo he cumplido mi deber a mi pais.” (Don Guillermo, I have fulfilled my duty to my country)

William Heath Davis – “Seventy-five Years in California”

Author: Axotl

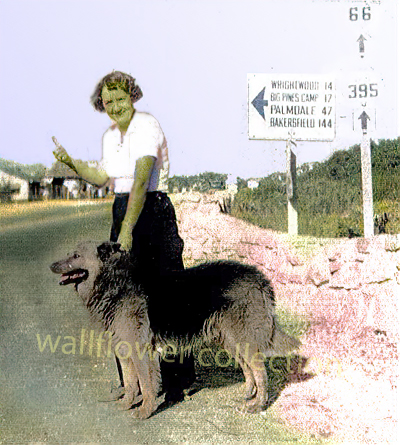

‘Gravel Gertie’

Part I

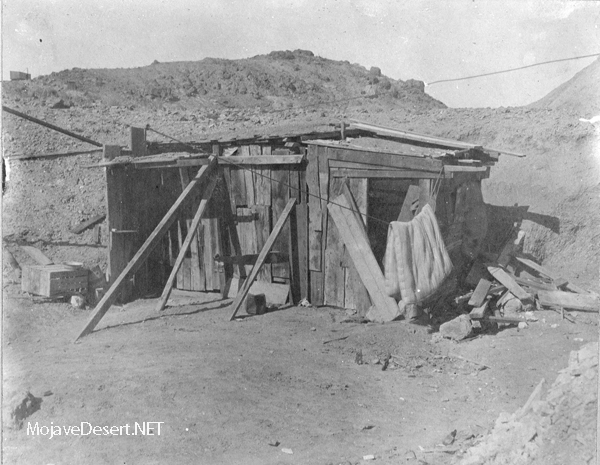

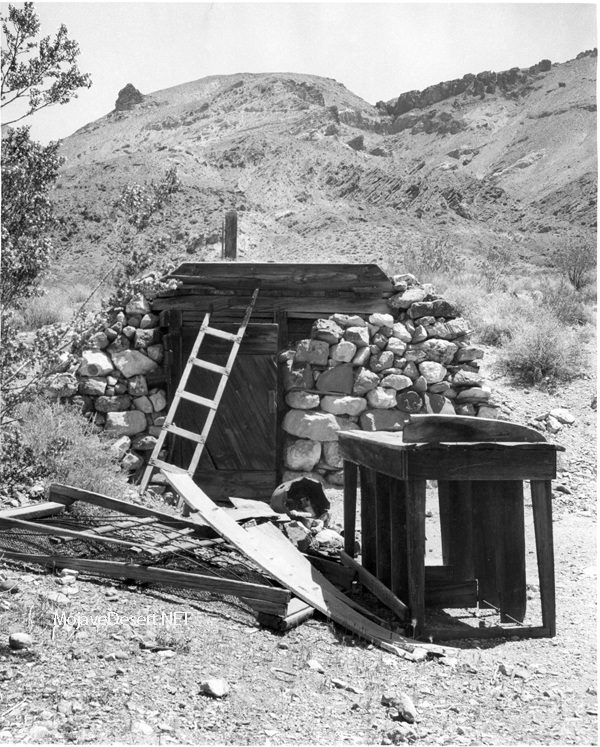

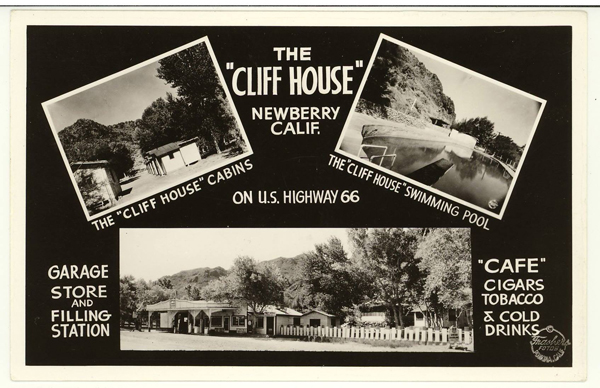

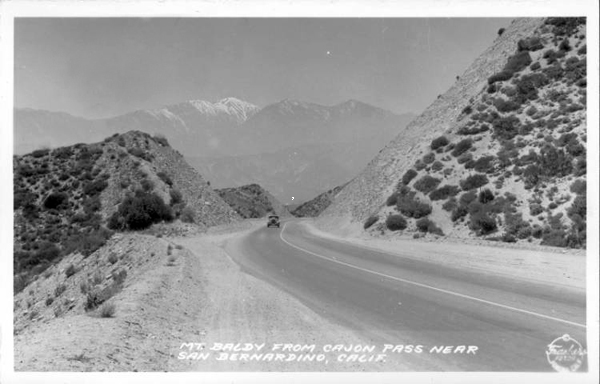

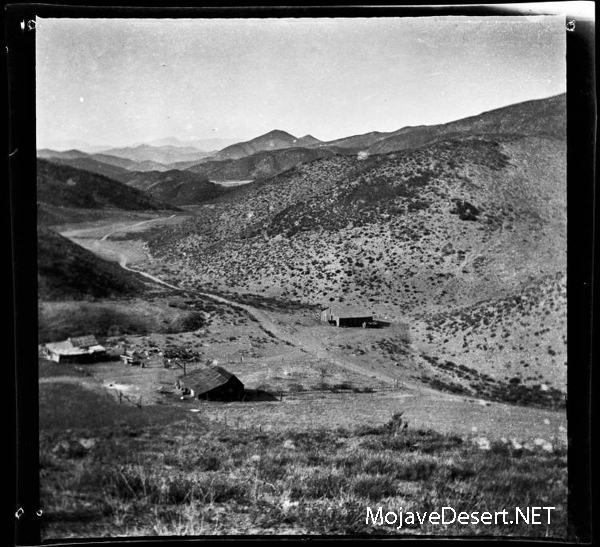

Juanita “Gravel Gertie” Inman lived in a shack off of the old Route 66 in the Cajon Pass at the southern edge of the Mojave Desert north of San Bernardino, California. “Gertie’s” shack wasn’t really a shack, it was a chicken coop, albeit a very nice chicken coop. There were plenty of windows to let in light and coverings and tarpaulins to cozy the place up in the wind and storms, and there was a stovepipe sticking out of the roof, indicating there was warmth available for the birds to keep them laying their eggs during the worst of times.

Plush quarters for the hens indeed. This shack, for looks and legal purposes, was a chicken coop–a hen house for pampered poultry.

During WWII, building materials were in short supply and available only for subsistence projects, such as watering troughs for hogs, horses, and milk cows. Structures for chickens, turkeys, and other such creatures were permitted.

So Gertie built her home under the auspices of creating a hen house. It was very nice inside with several rooms and a fireplace. The county would check on projects like these, but from a reasonable distance, it looked like chickens lived there. They didn’t, though. The chickens were kept outside in a wire coop.

—

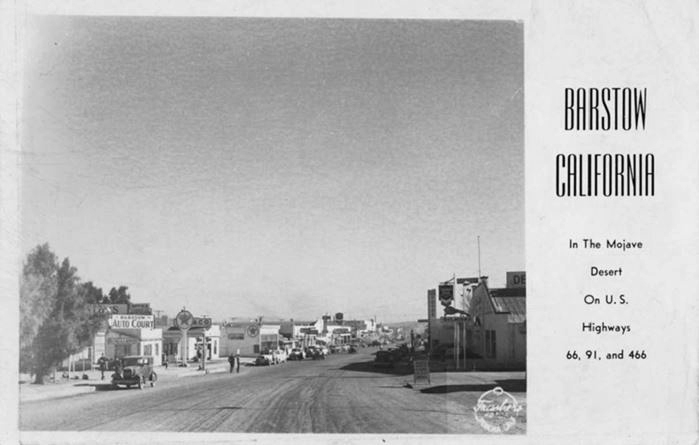

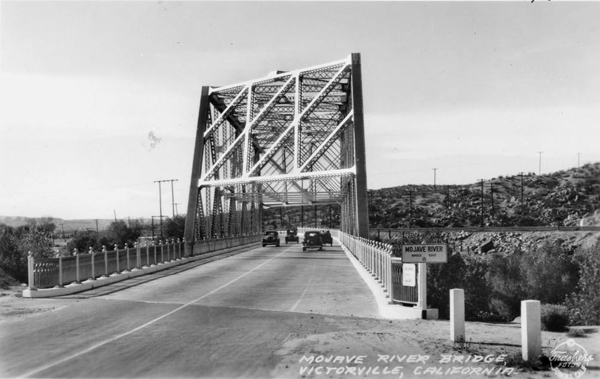

Wrong-Way River

by walter feller

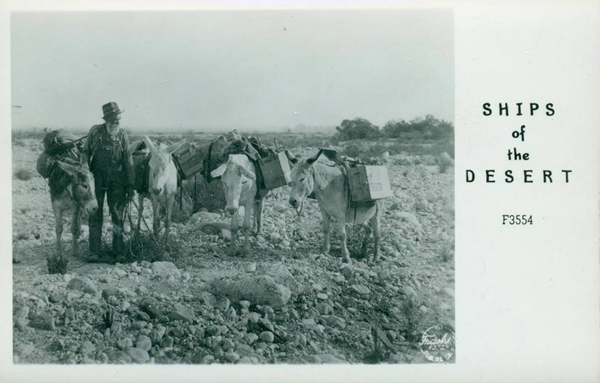

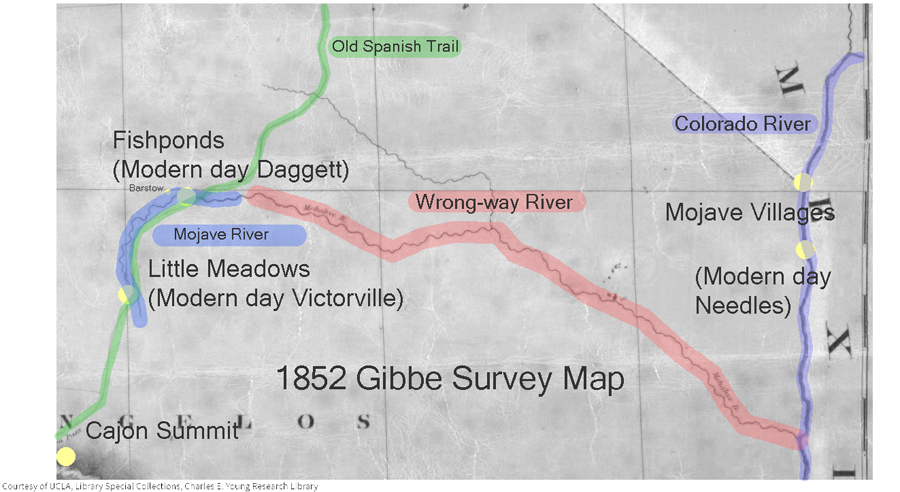

In 1852 a survey was made of the southwestern edge of the Mojave Desert. The Old Spanish Trail # had become a wagon road bringing thousands of pioneers to the west and developed as a supply route between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City. The survey was as accurate as any at that time and followed the trail from near the top of the Cajon Pass to a point where the trail leaves the Mojave River near Fishponds. The trail to Salt Lake continues north as we know it, but the river flowing east on this map bears southeast and empties into the Colorado River. At the time it was thought the Mojave (spelled Mohahve on the map) River followed this course. It did not. There was no Mojave Road in 1852 and not many Americans had traversed that portion of the desert. As we now know the Mojave River cuts through Afton Canyon and then disappears into the sink of the Mojave before it reaches Soda Lake.

The Williamson survey the next year in 1853 begins to correct the true ancient course of the river as it would have found its way to converge with the Amargosa River and empty into Death Valley’s Lake Manly via Soda Lake, Silver Lake, Silurian Lake, and Salt Springs.

-End –

Indian Queho.

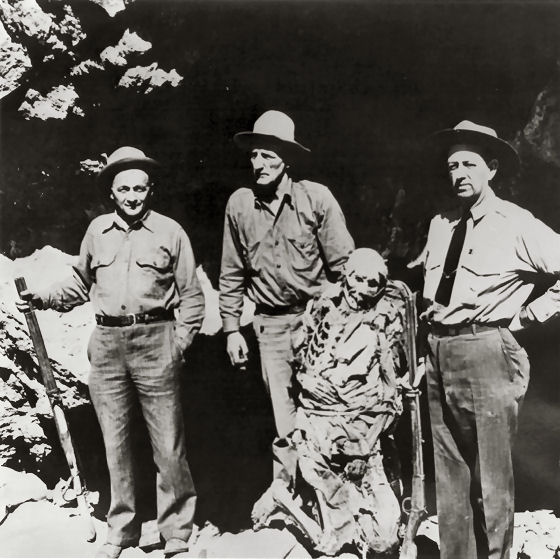

Subject: – – Mummified remains of an Indian renegade known as Queho. Many years previous to when this photo was taken in the early 1940s, Queho is said to have killed and robbed a number of individuals in the Searchlight, Nevada area. Unsuccessful efforts were made to apprehend Queho.

In the early 1940s, the men pictured here on the left and right were exploring an area along the Colorado River when they saw a cave in the cliffs above the river. they climbed up to the cave and Queho’s remains were found. Research had established that the remains were Queho’s because several of the artifacts he had stolen from people in Searchlight accompanied the remains.

Queho’s remains were turned over to the Palm Mortuary in Las Vegas when a question arose as to who would pay for the expenses of keeping Queho there and his burial. Roland Wiley, district attorney for Clark County, Nevada, at the time, suggested that the remains be turned over to the Elks Lodge, where for a number of years they were exhibited on the Heldorado grounds during Heldorado days in a glass display case with some of the stolen artifacts.

Queho’s remains were stolen from the Elks on 2 occasions, and each time they were recovered. Jim Cashman, head of the Las Vegas Elks at the time, grew tired of worrying about the theft of Queho’s remains so they were moved to a building belonging to Dobie Doc Caudil near the Tropicana Hotel.

Roland Wiley purchased Queho’s remains from Dobie Doc for $100 and buried them near Cathedral Canyon, located on Wiley’s ranch in Pahrump Valley overlooking his Hidden Hills airstrip, in concrete and steel so they could not be easily stolen again. Wiley believed the Indian deserved a decent burial and buried popcorn with the remains to accompany Queho on his journey.

The Renegade

On February 21, 1940, the banner headline in the Las Vegas Review-Journal— BODY OF INDIAN FOUND— recalled for many in the town memories of the first murder the dead Indian had committed, thirty years earlier at Timber Mountain, just a few miles from Searchlight in the McCullough Range. . . .

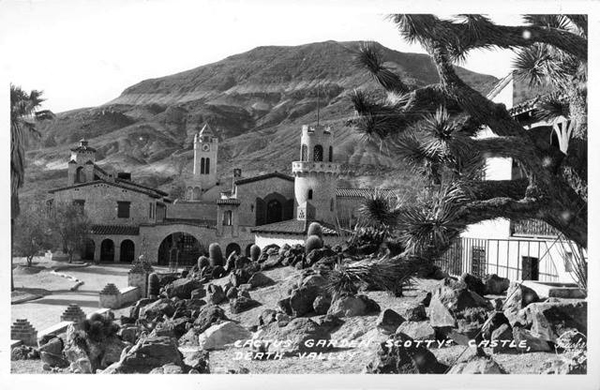

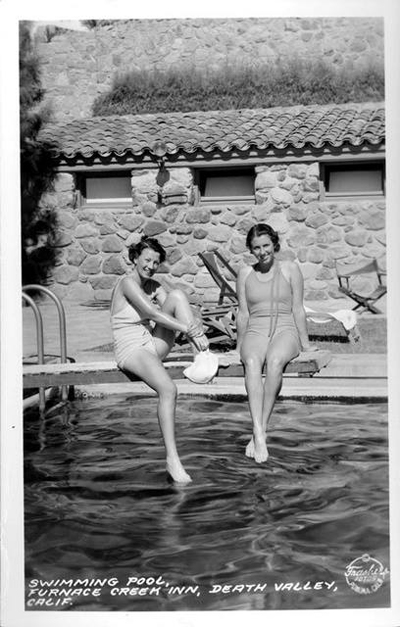

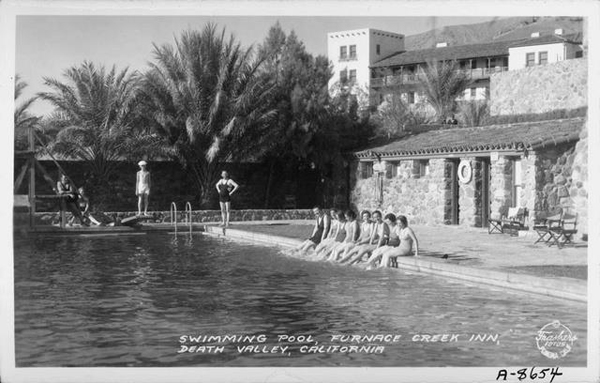

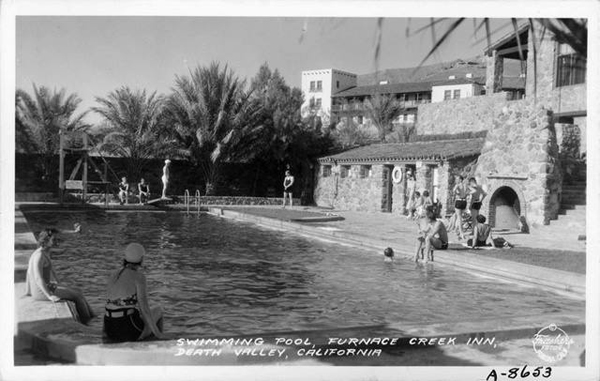

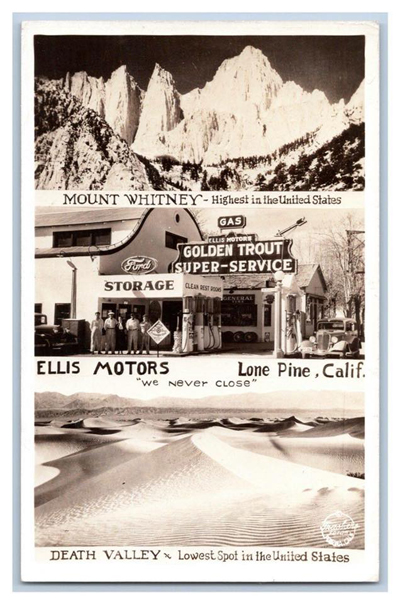

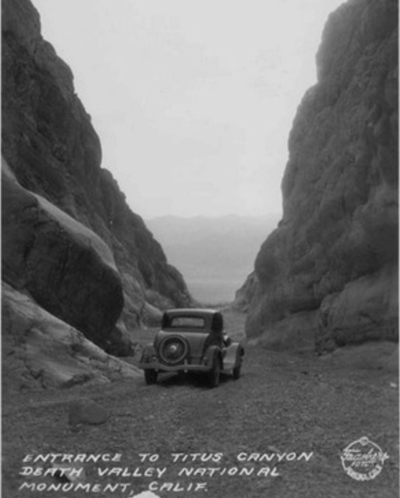

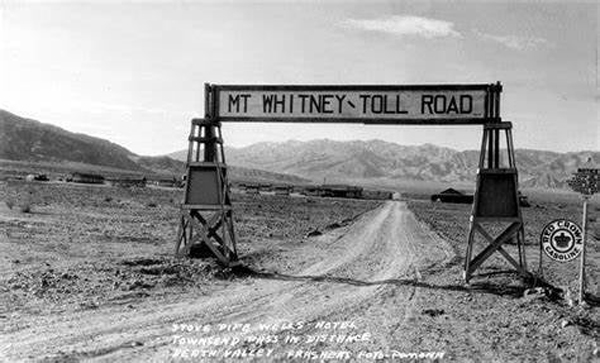

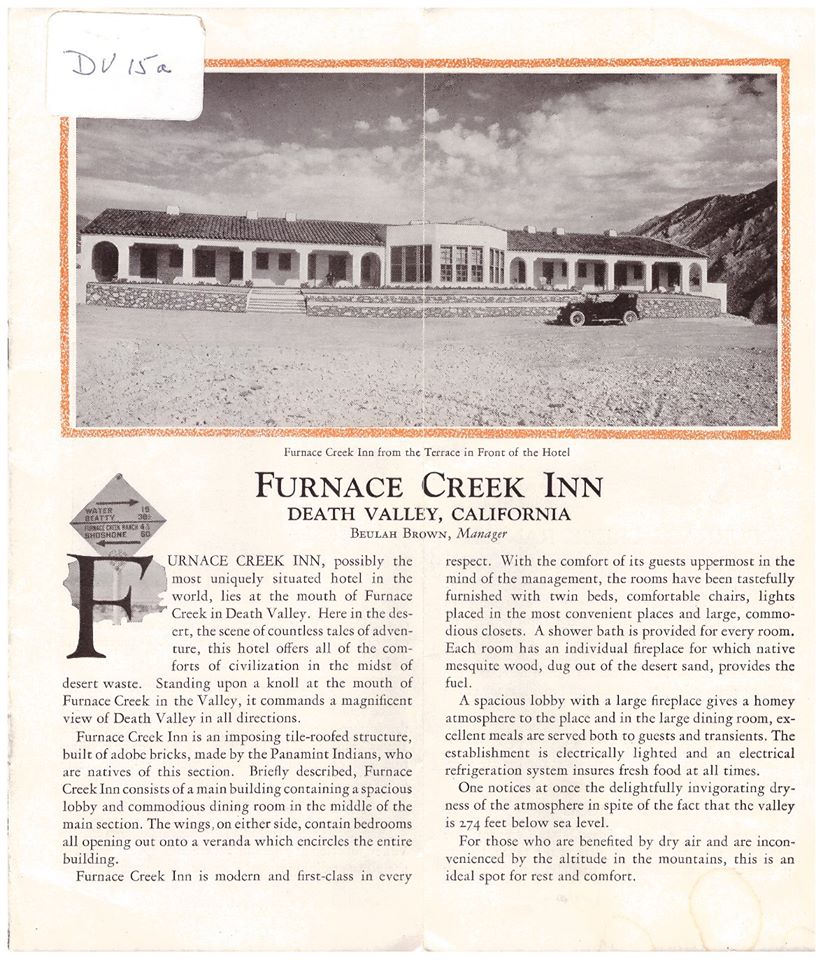

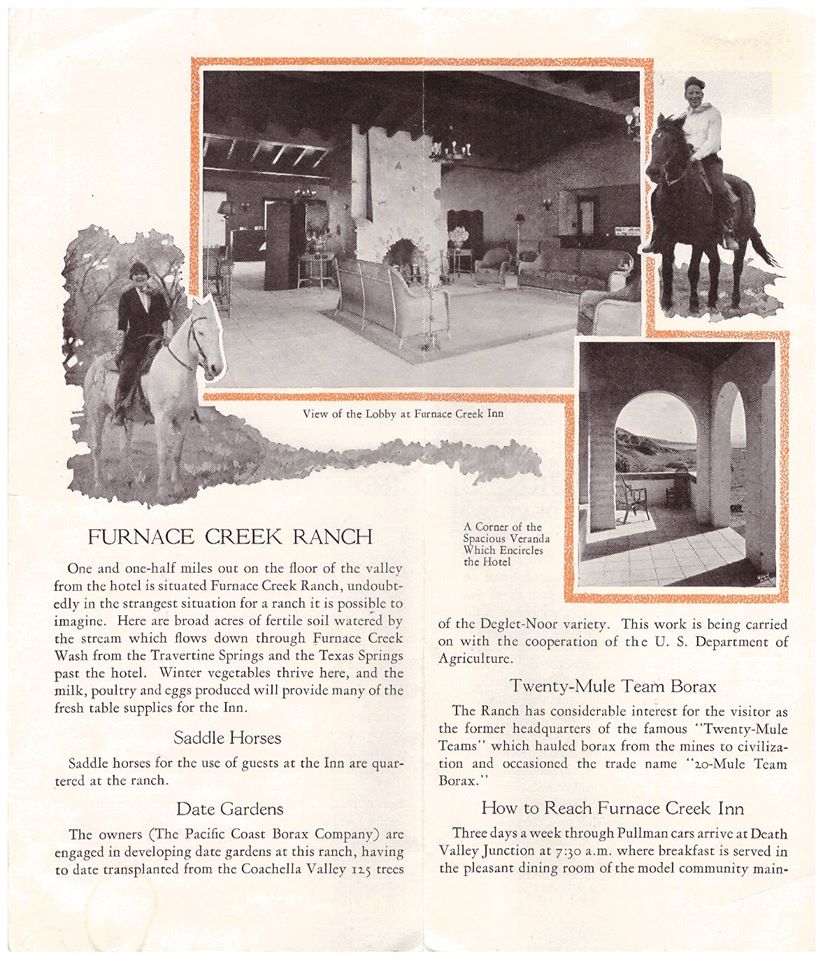

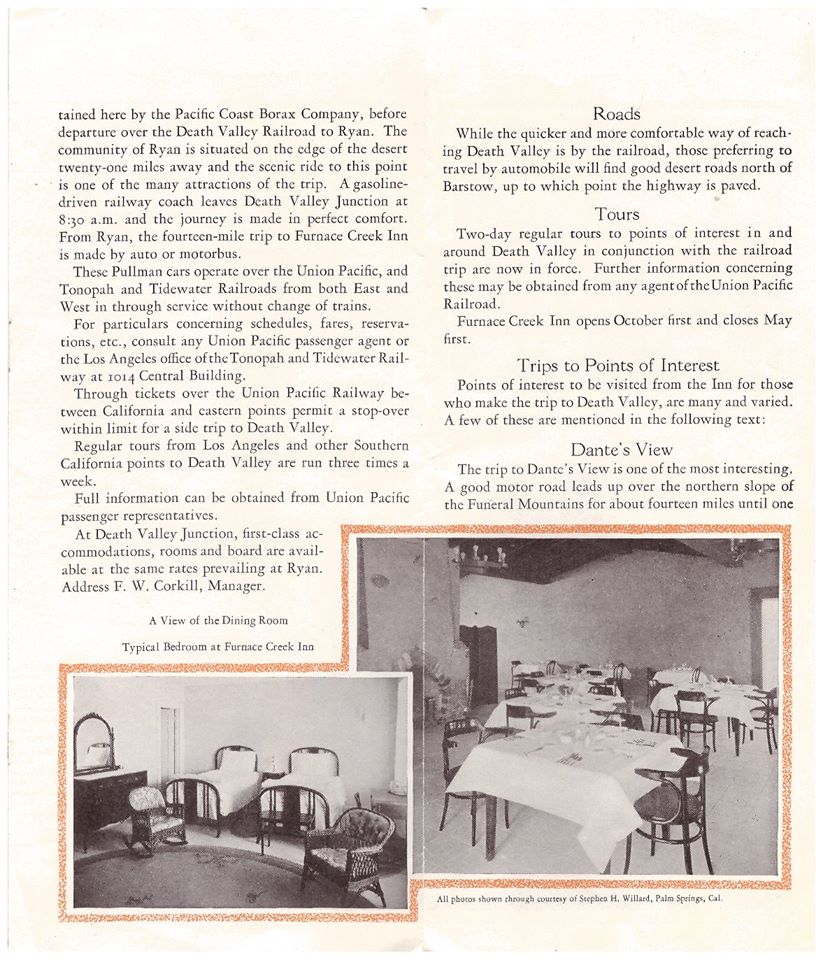

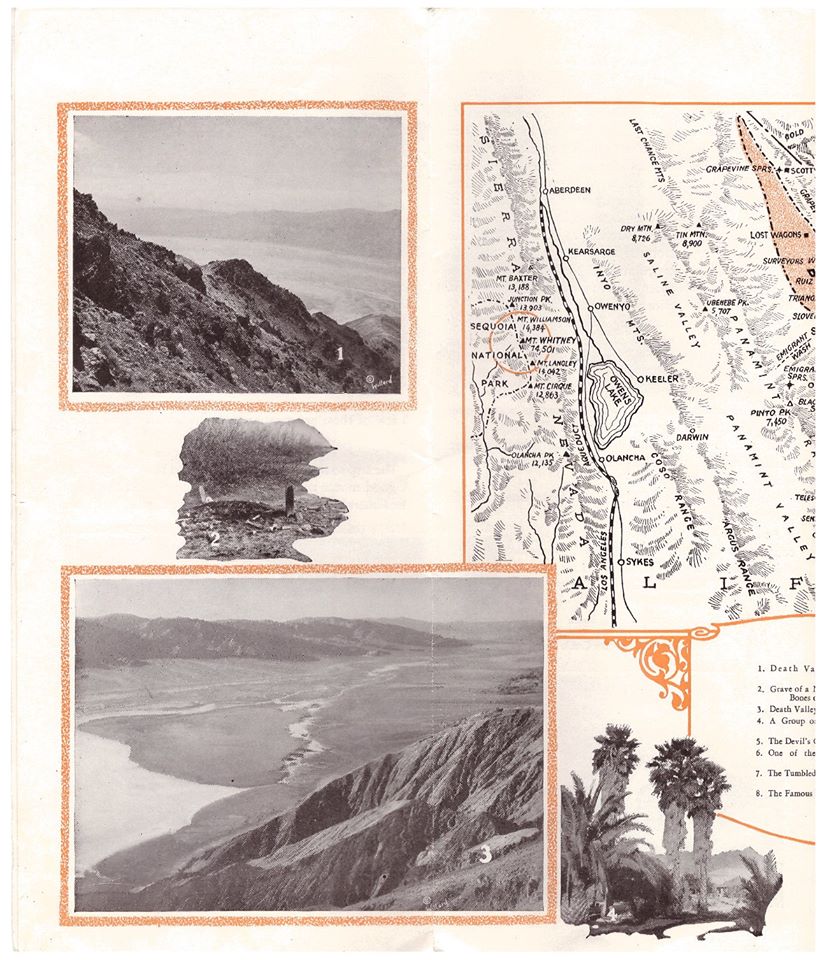

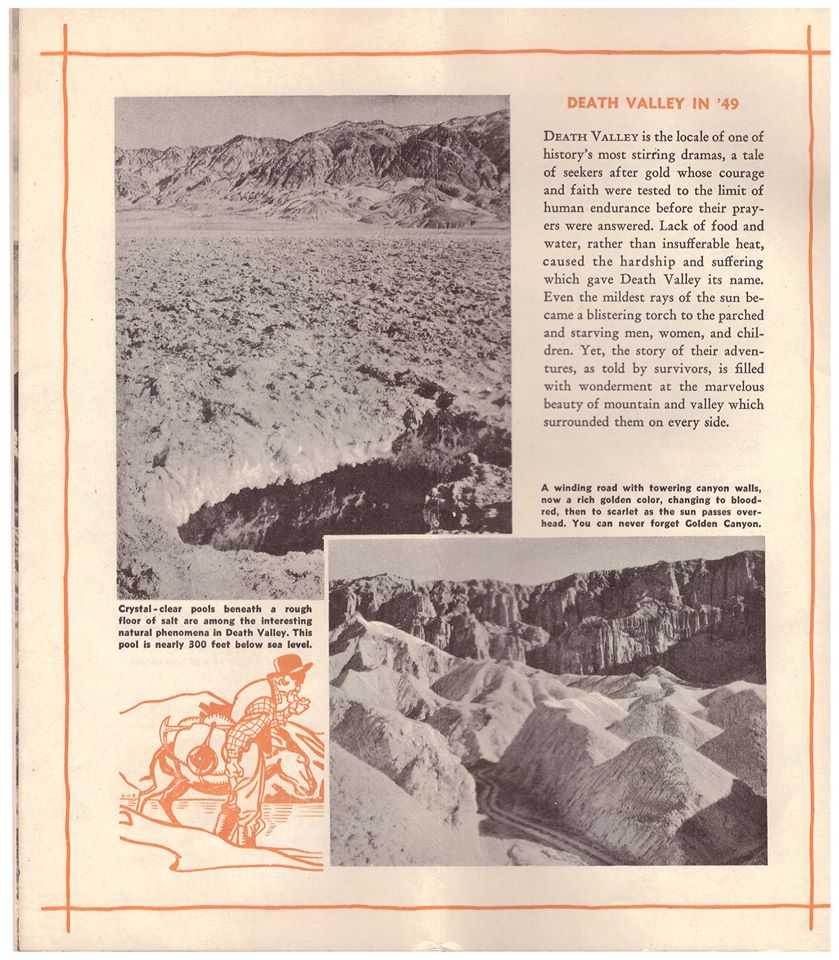

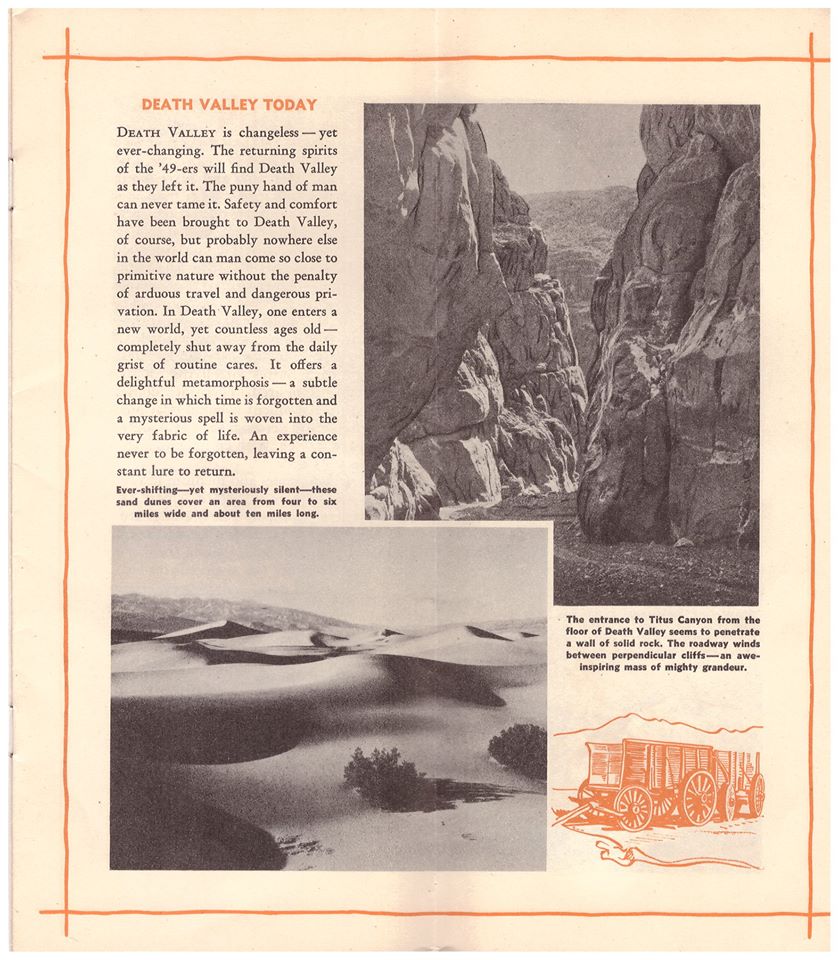

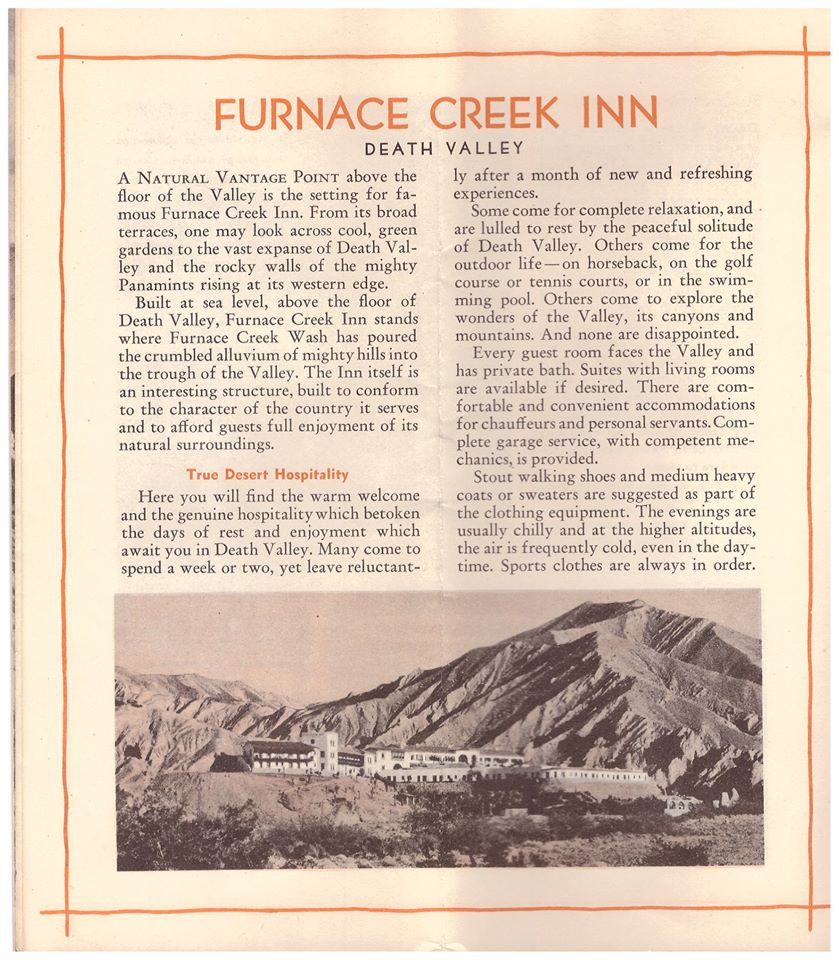

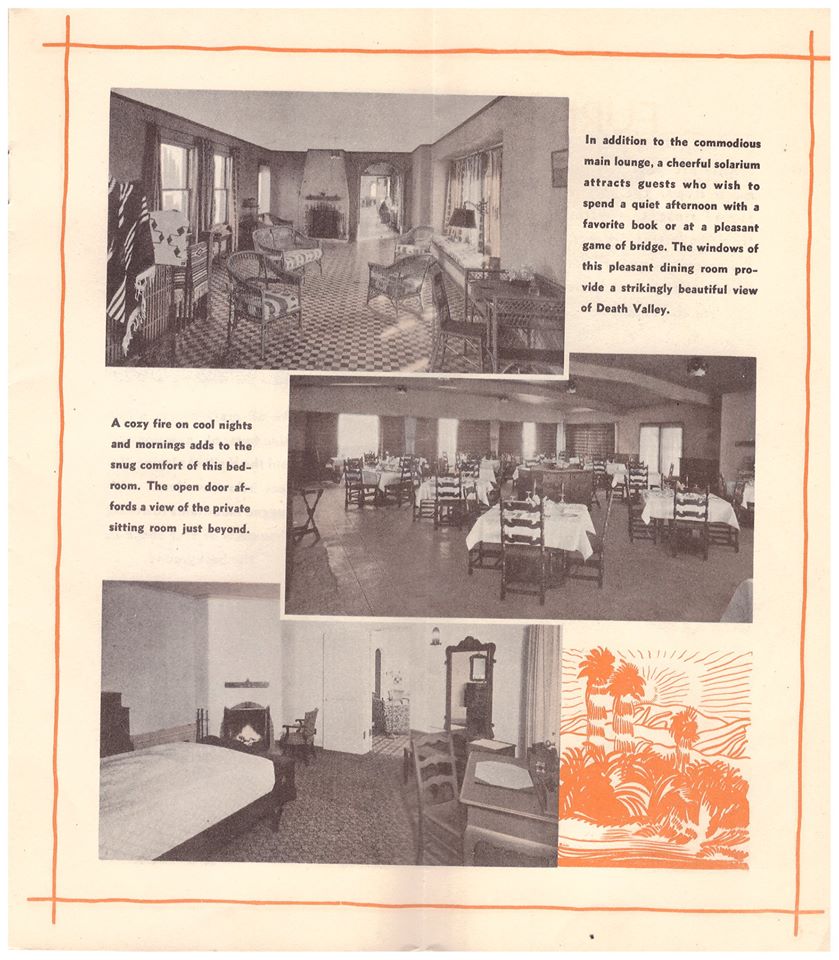

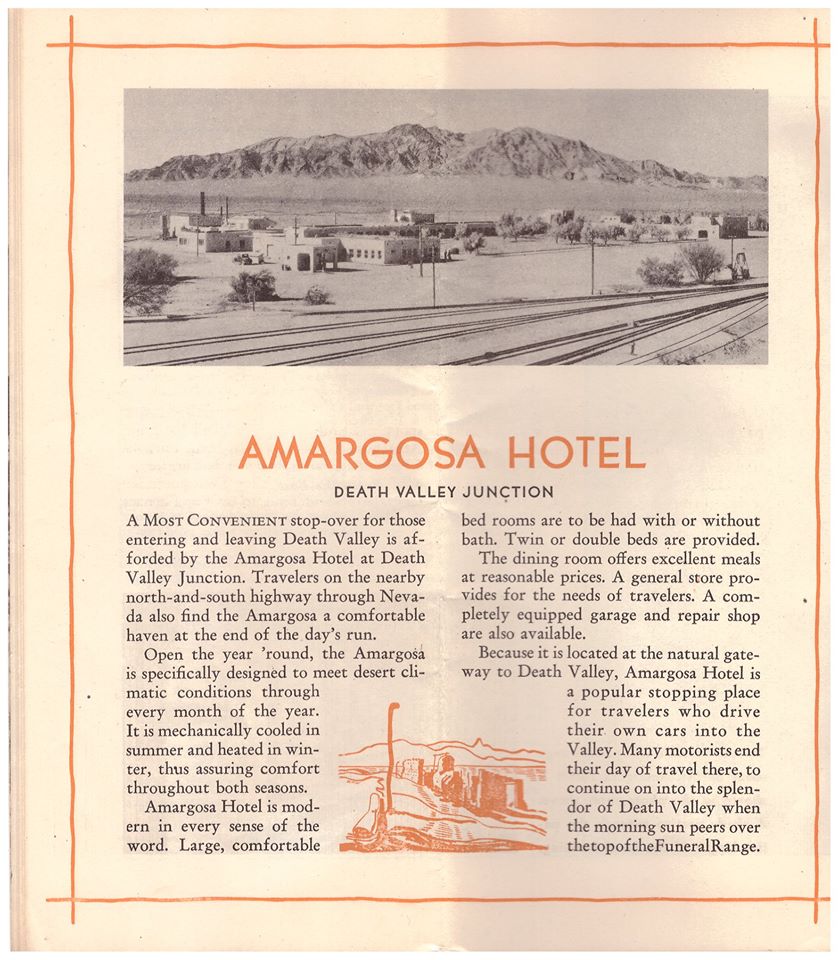

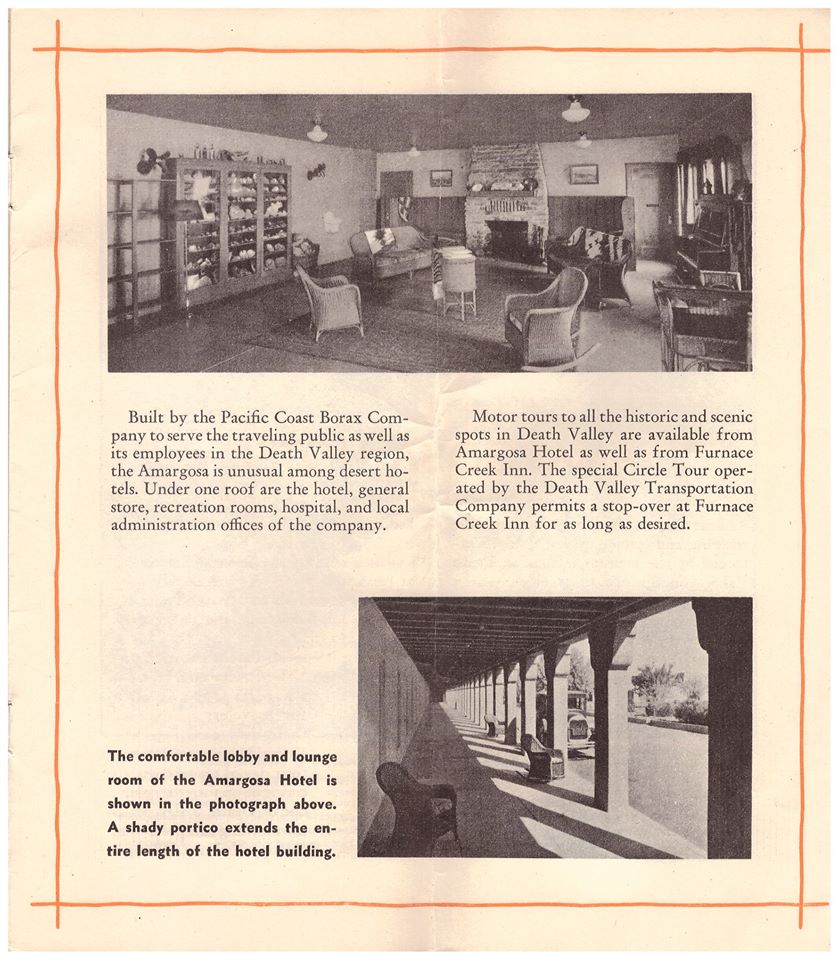

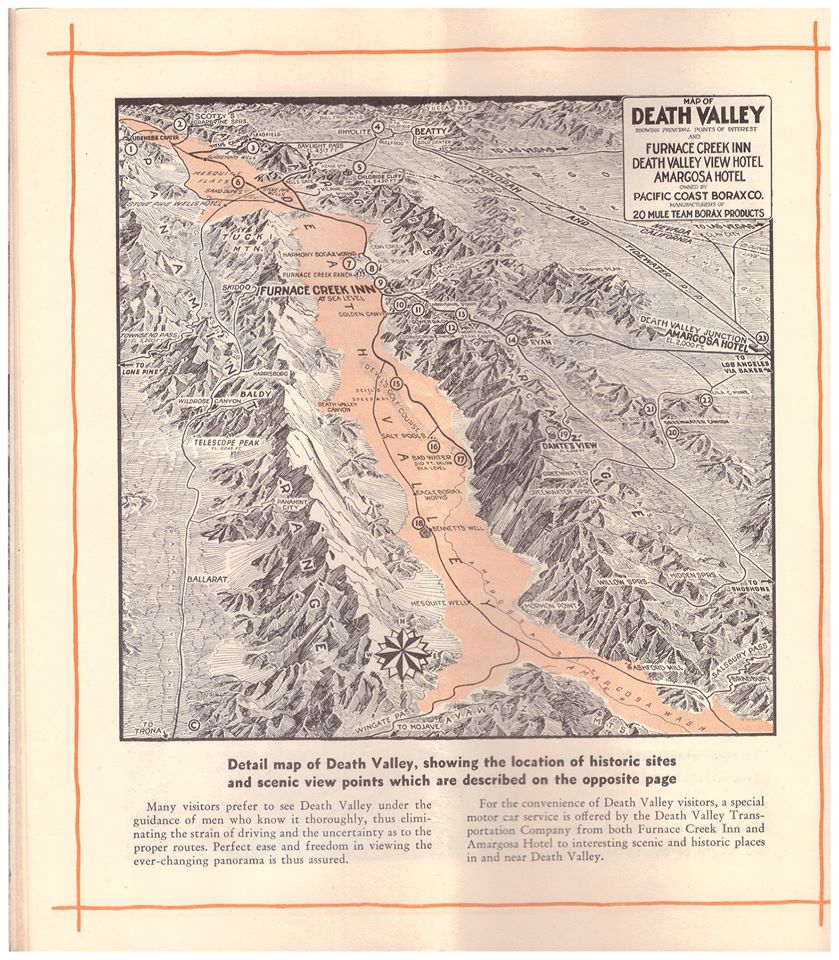

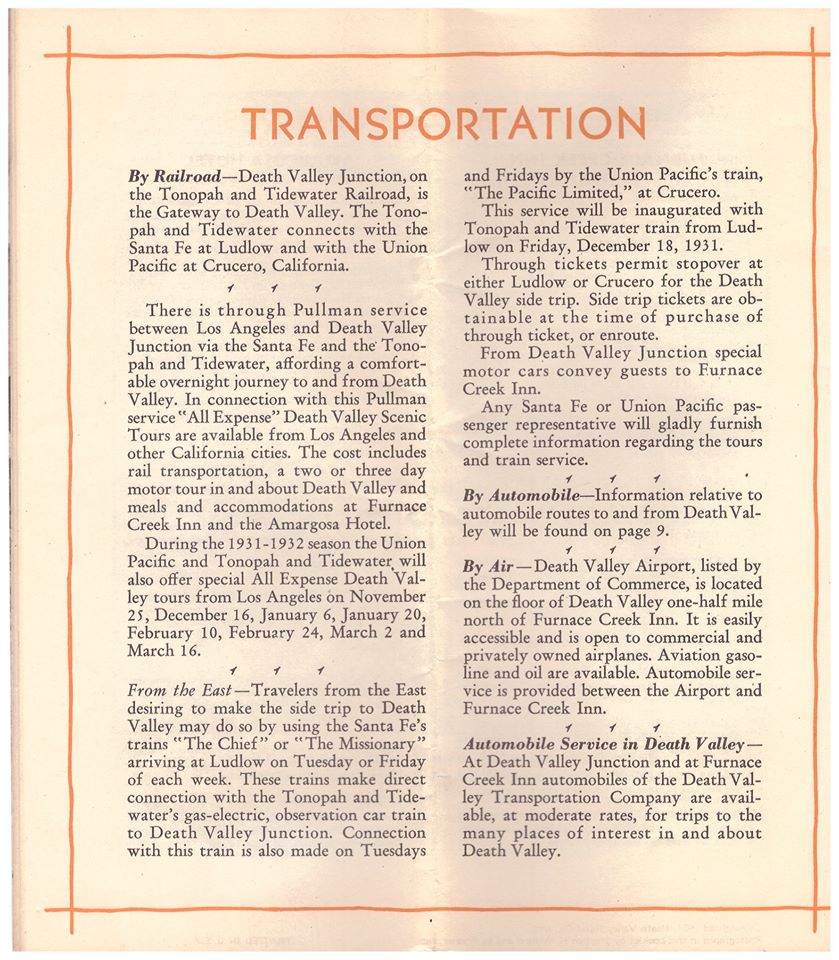

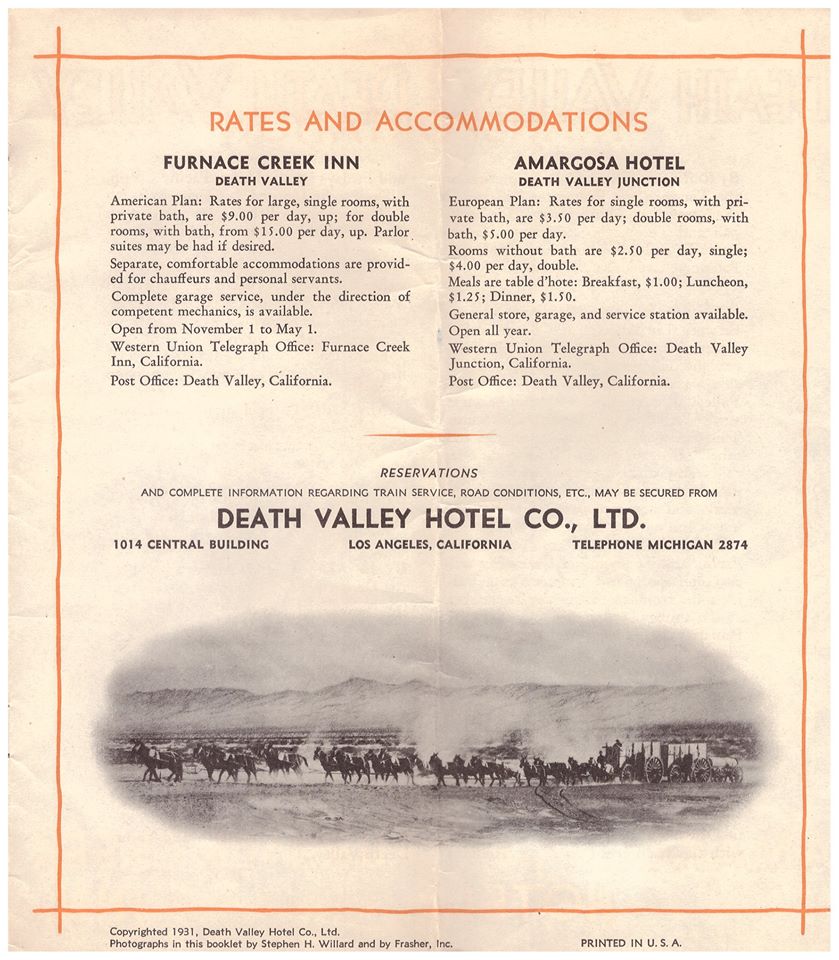

Death Valley Brochures

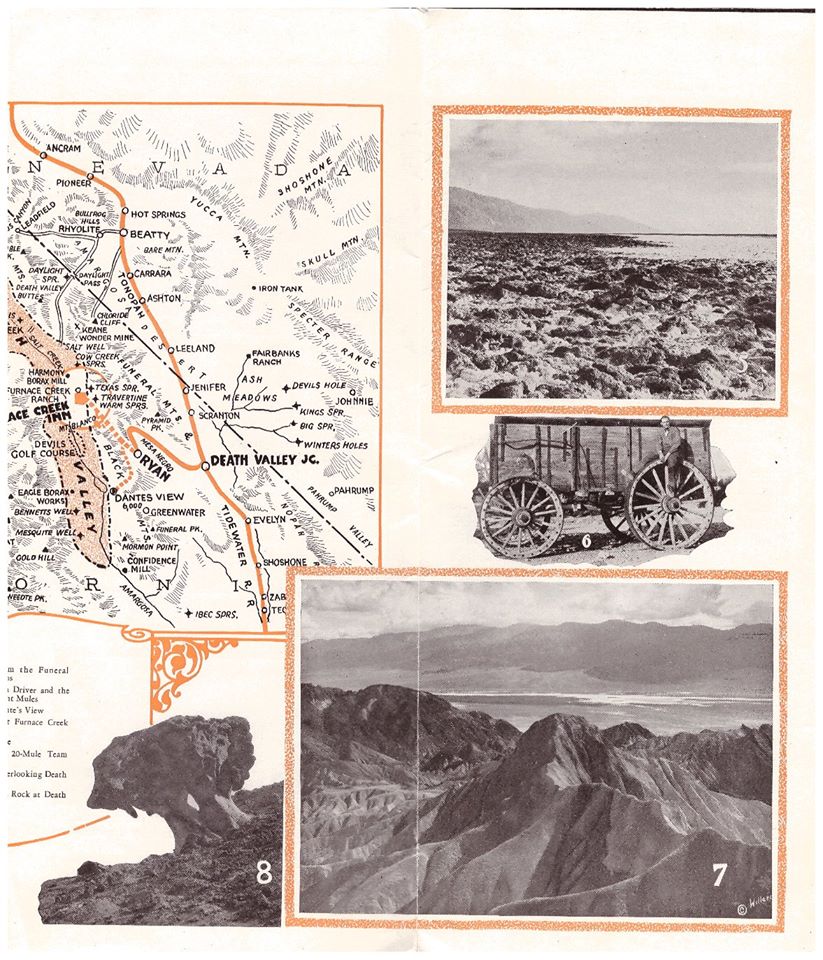

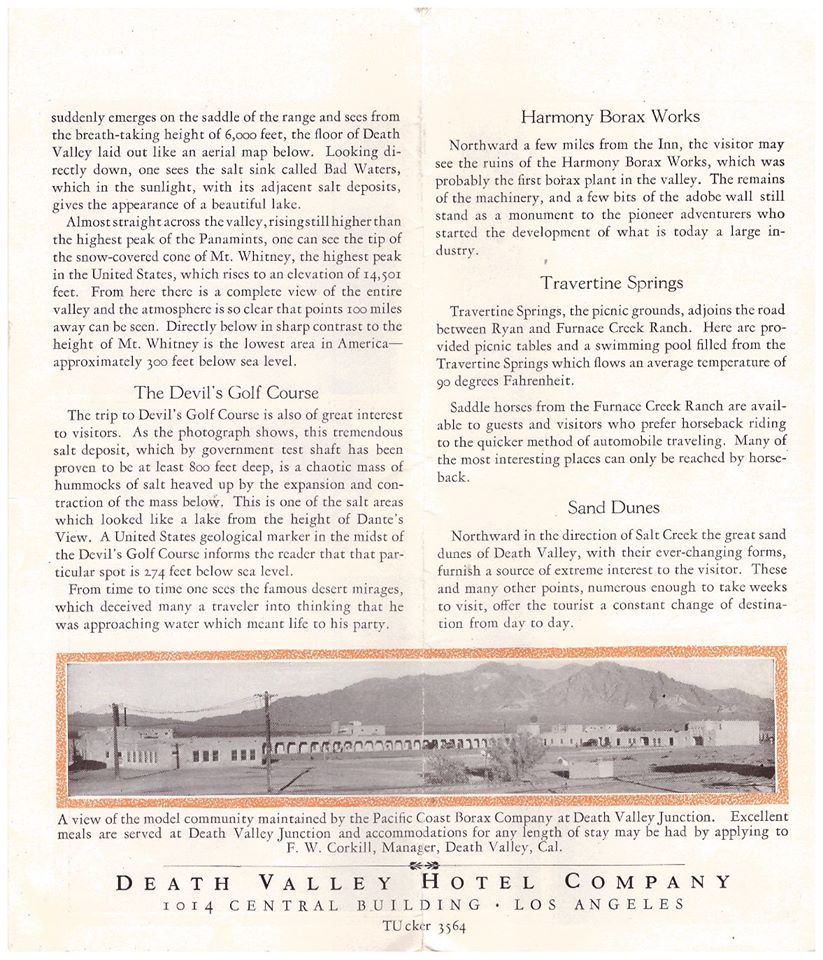

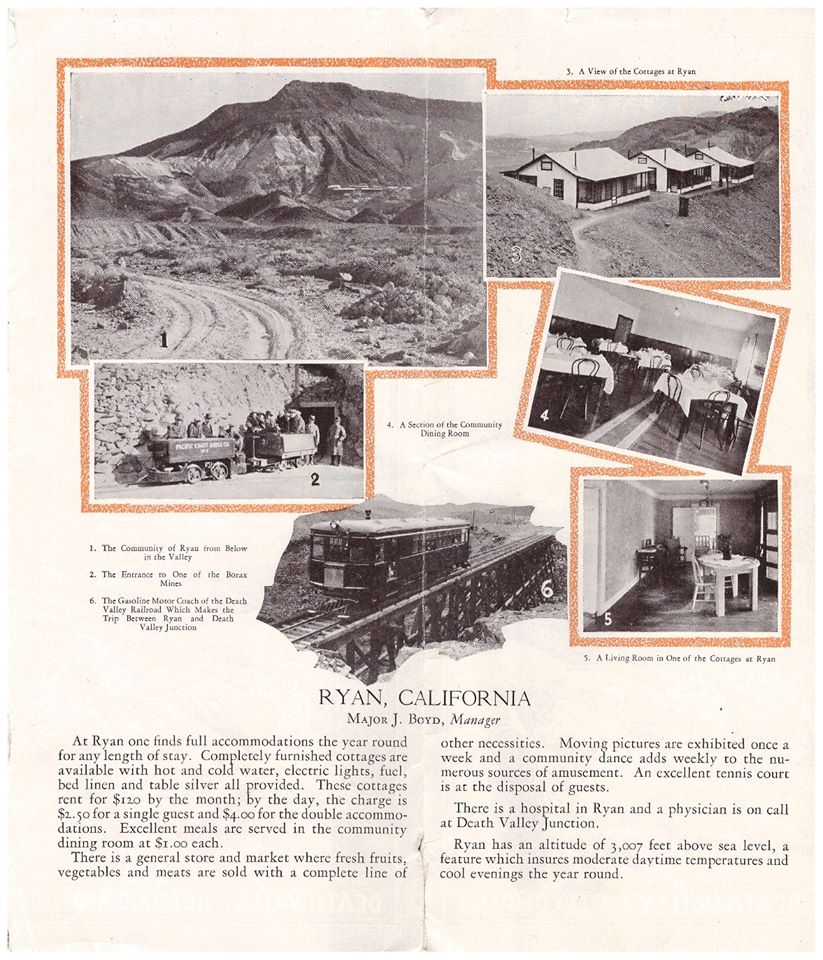

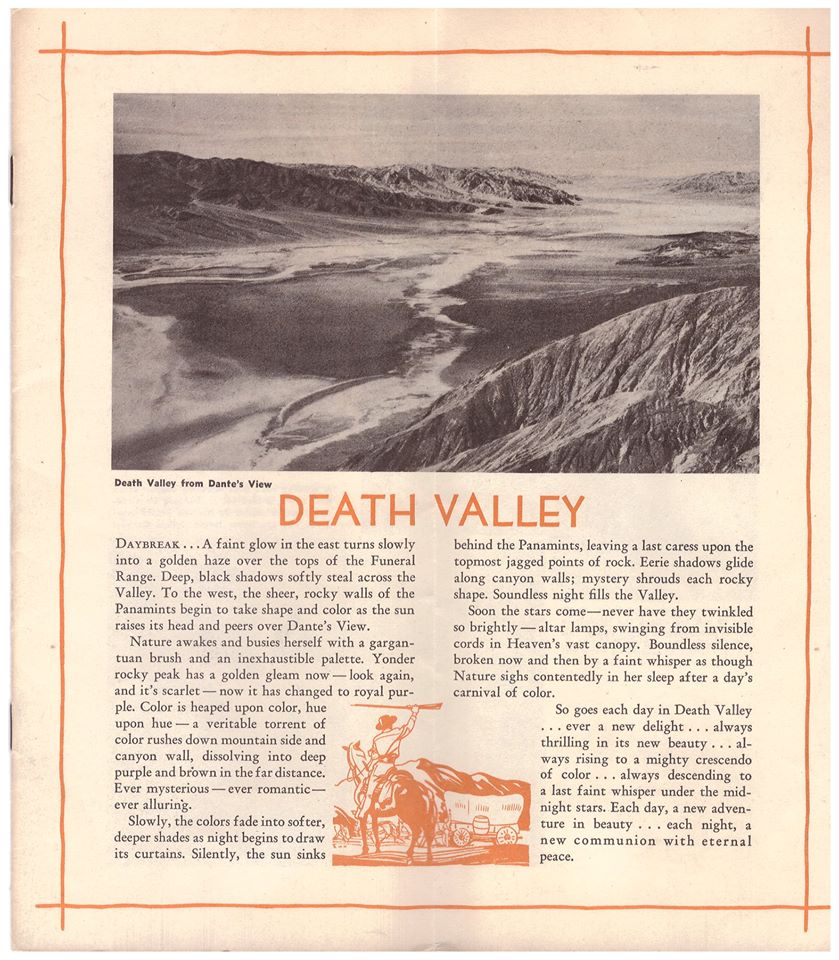

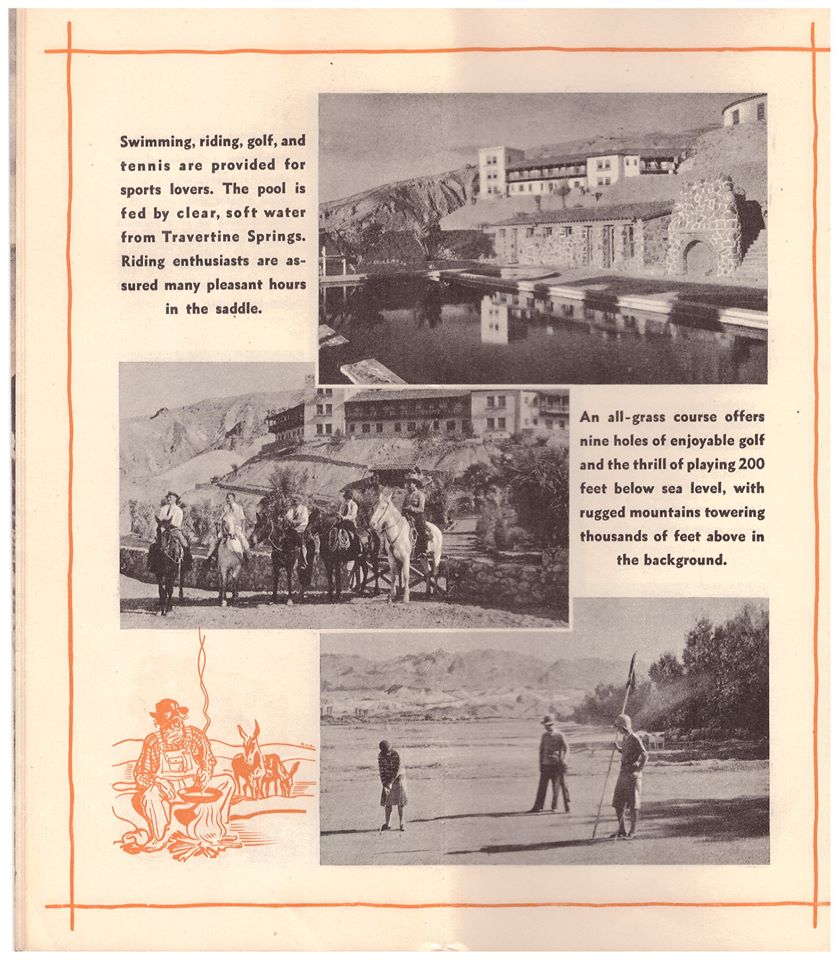

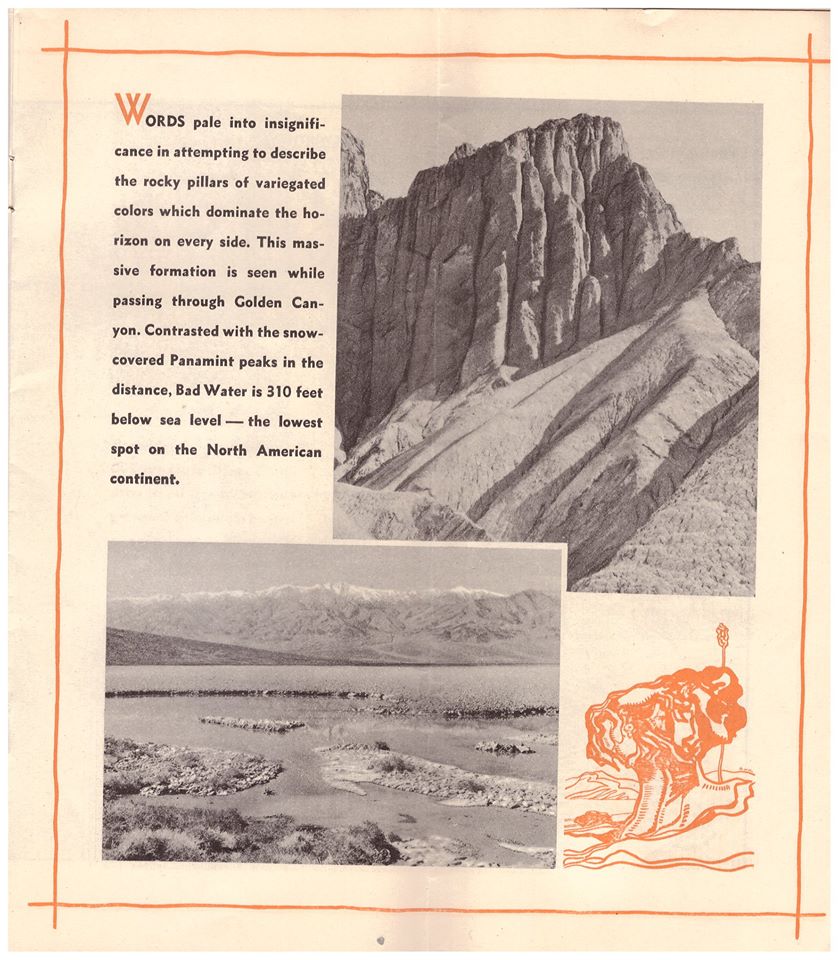

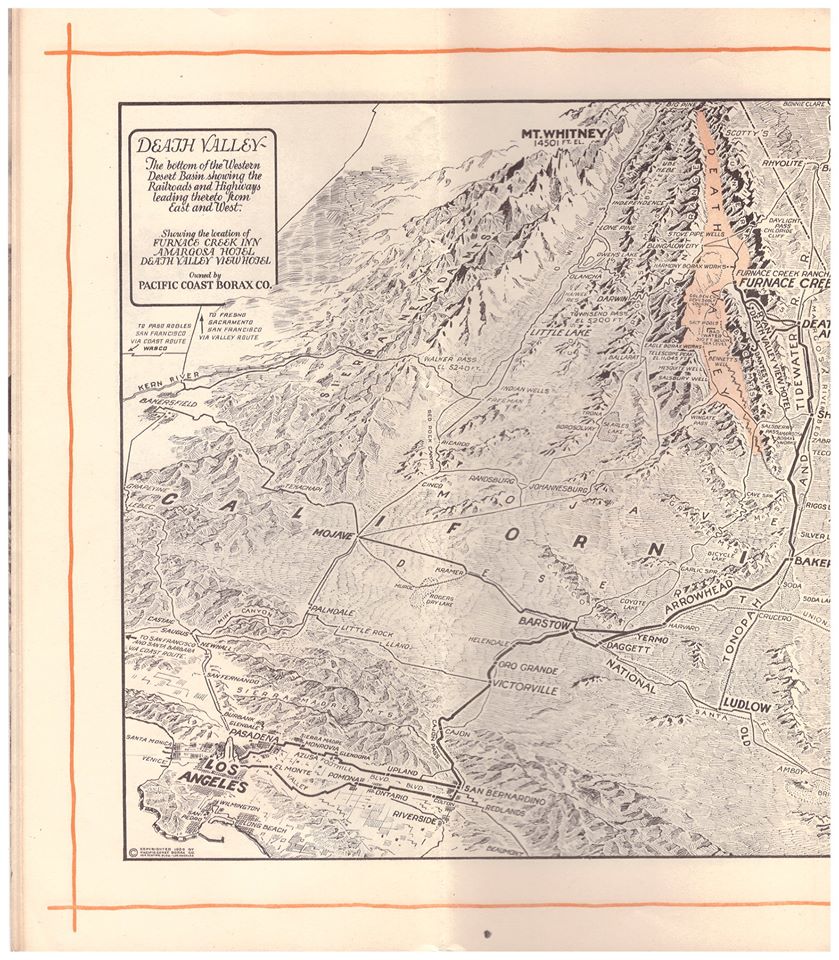

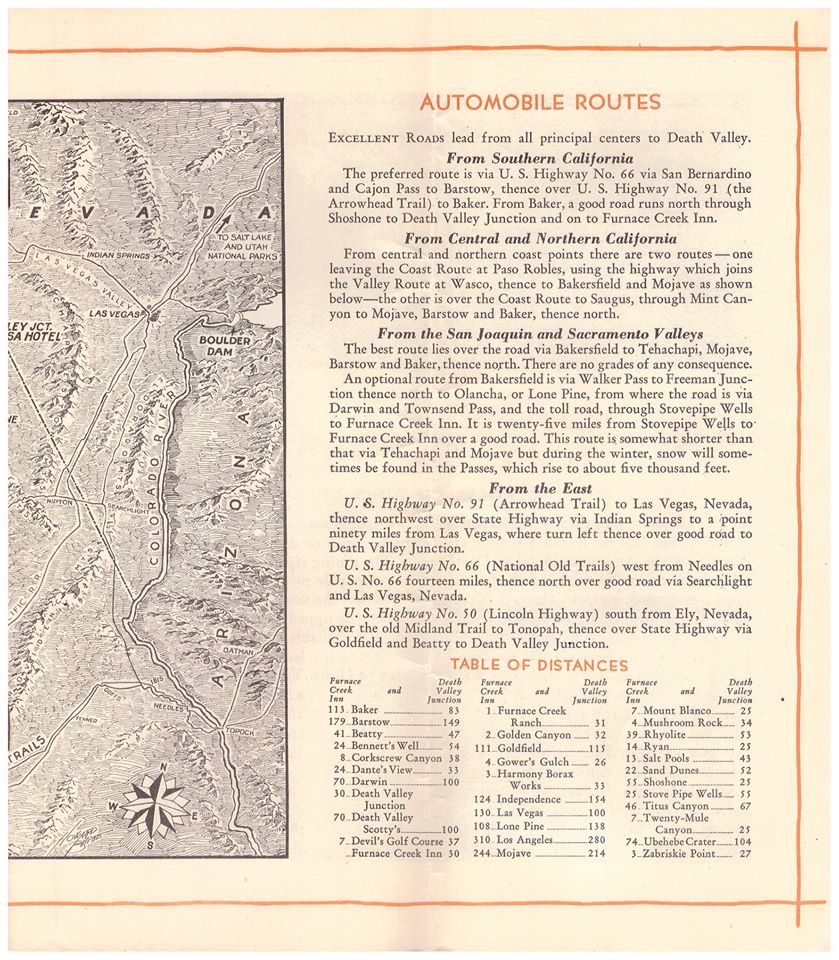

Featuring Amargosa Hotel, Death Valley Junction & Furnace Creek Inn, Death Valley – 1931

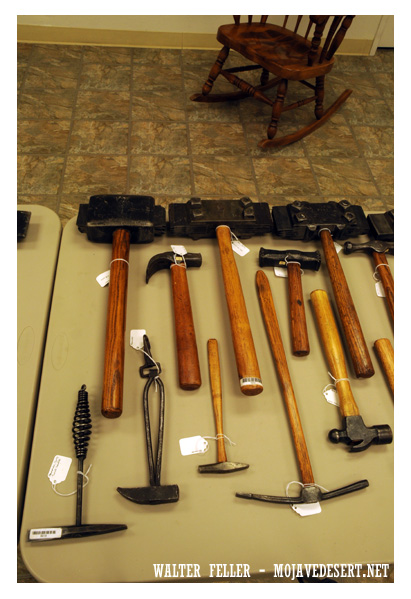

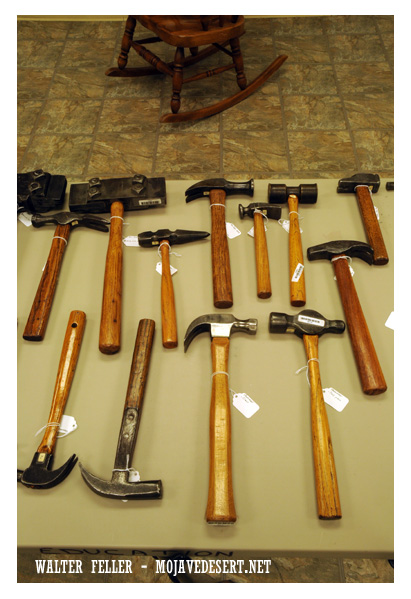

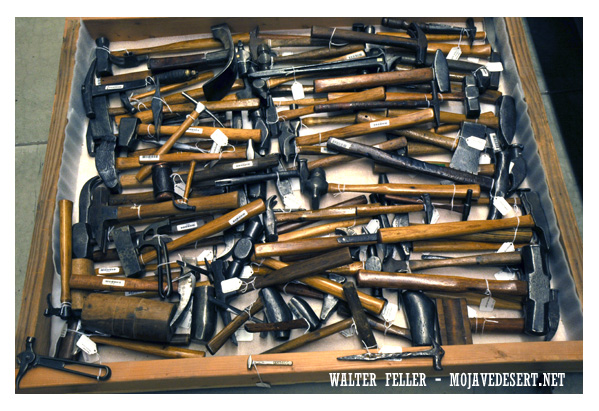

Hammers

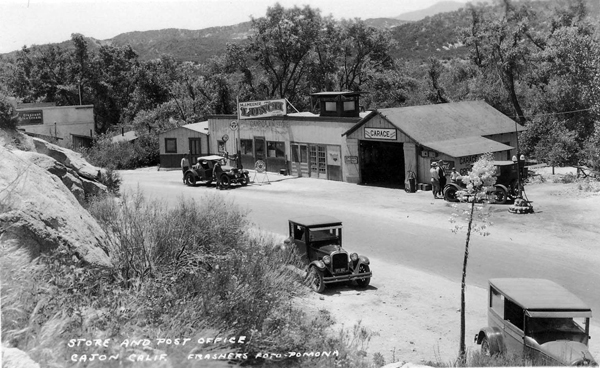

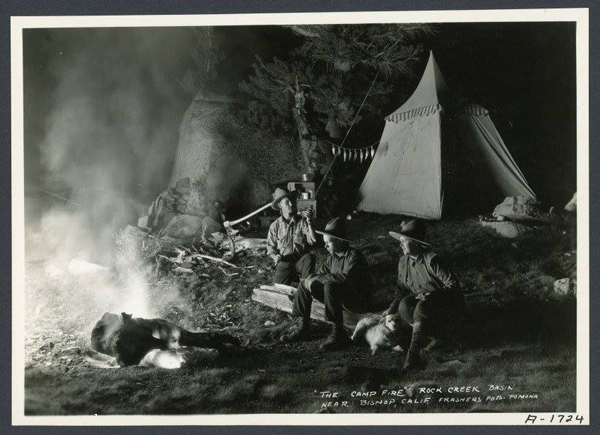

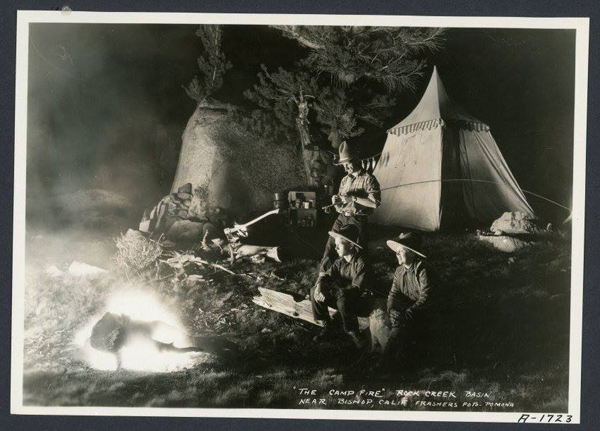

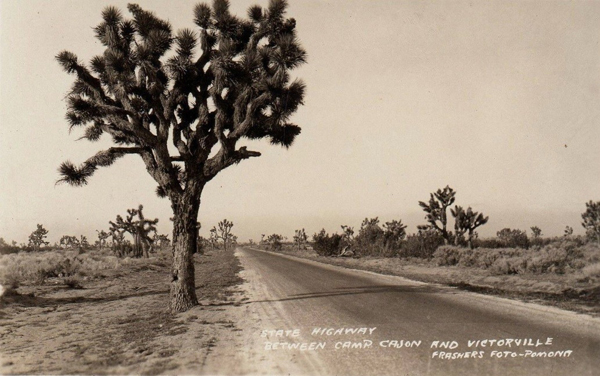

Burton Frasher

George Hazard

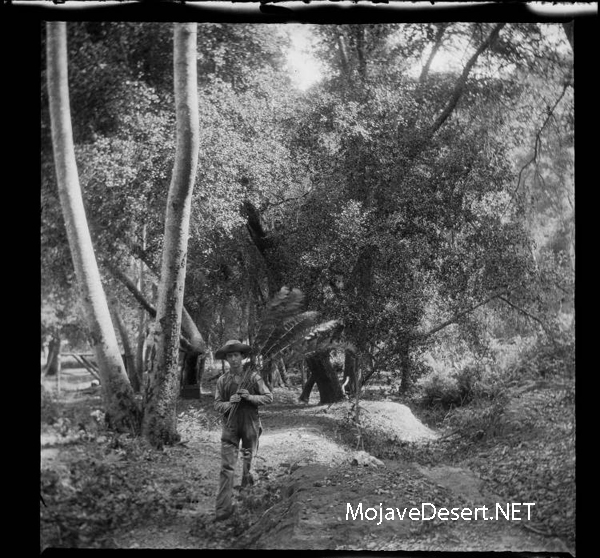

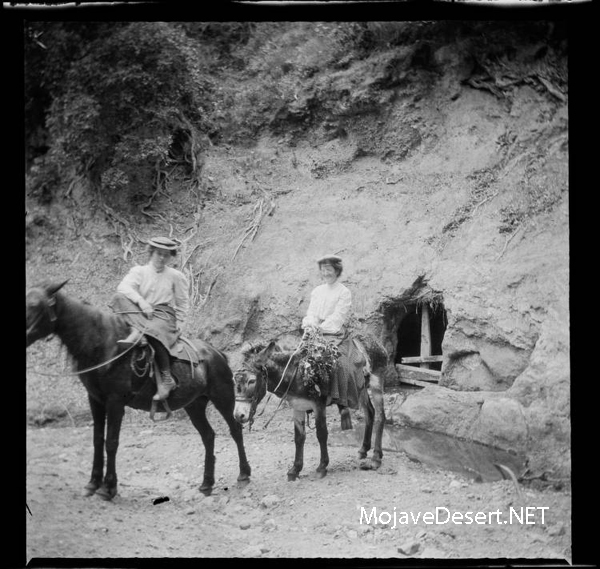

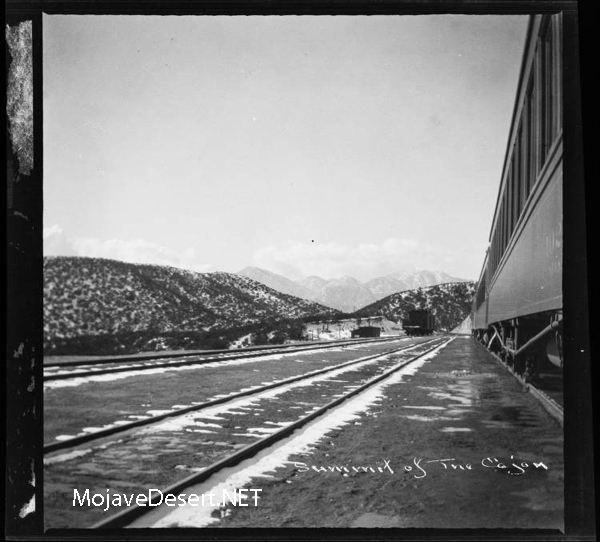

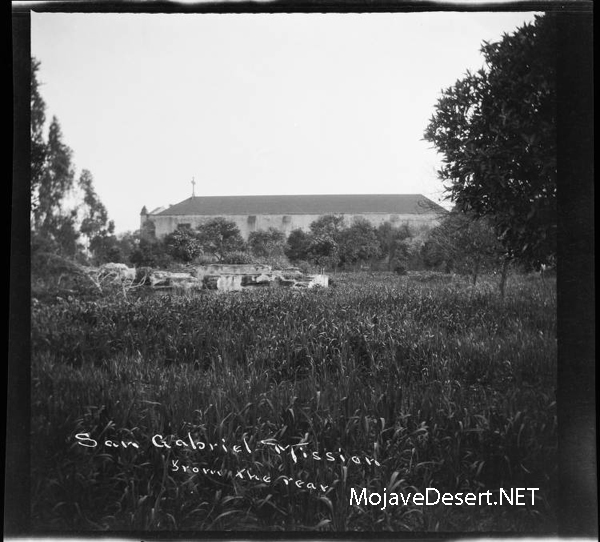

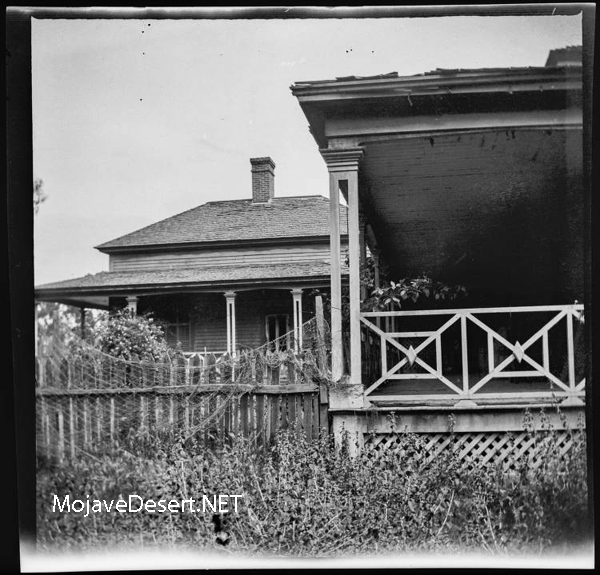

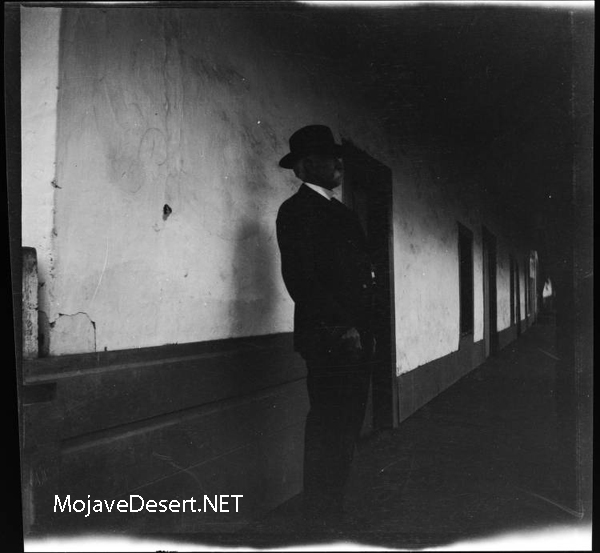

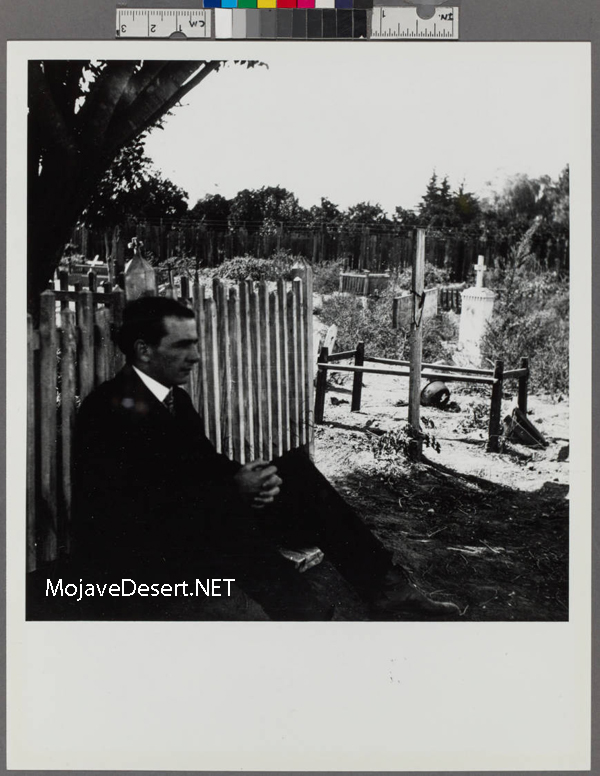

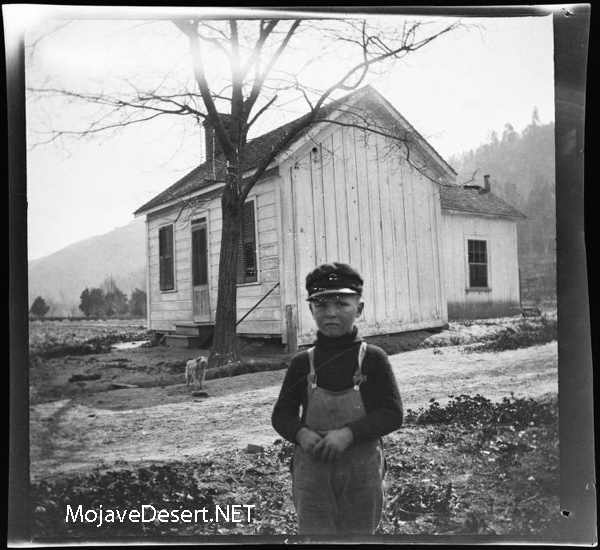

Antelope Valley, Leona Valley, Cajon Pass, San Gabriel, Wolfskill, Nadeau (see OAC)

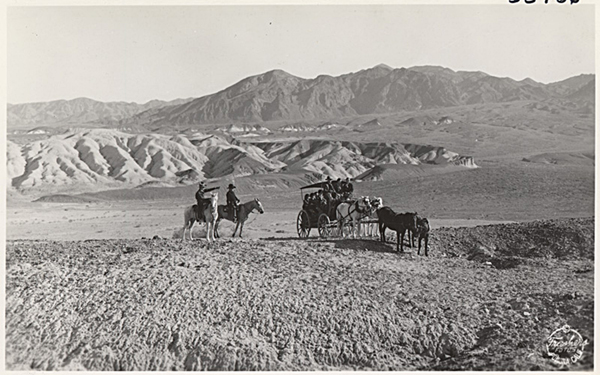

| These images were part of a set taken by Los Angeles historian and amateur photographer George W. Hazard (1842-1914), during his years traveling throughout Southern California photographing locations of local historical significance. – Courtesy Huntington Library |

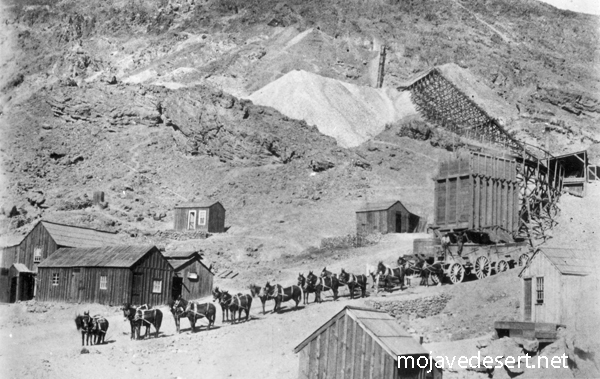

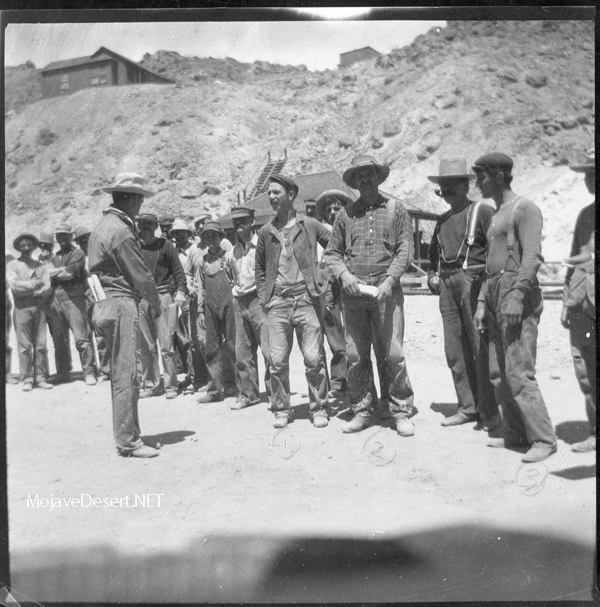

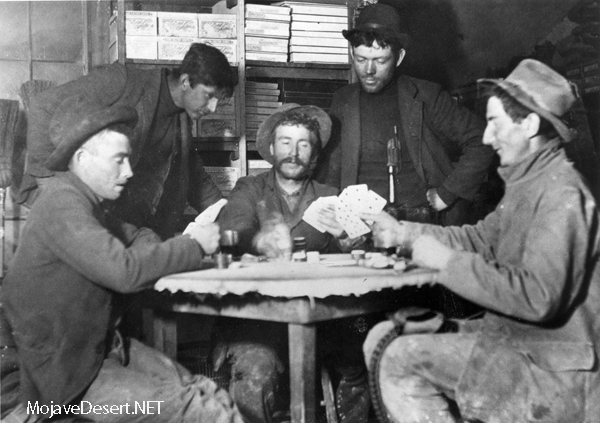

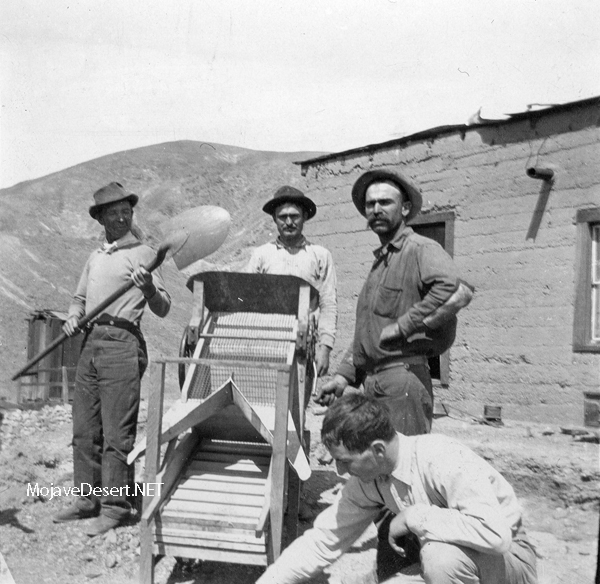

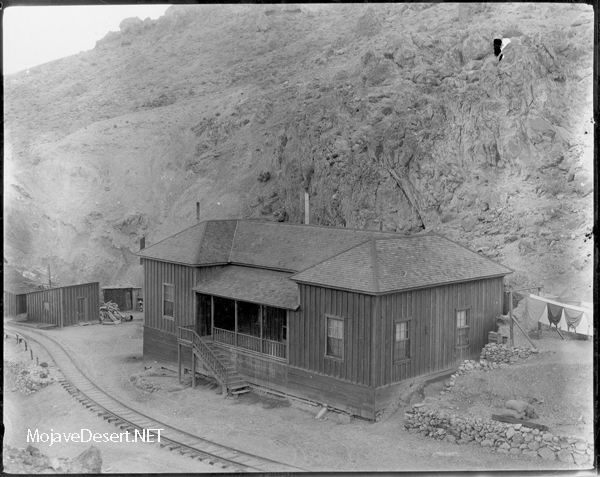

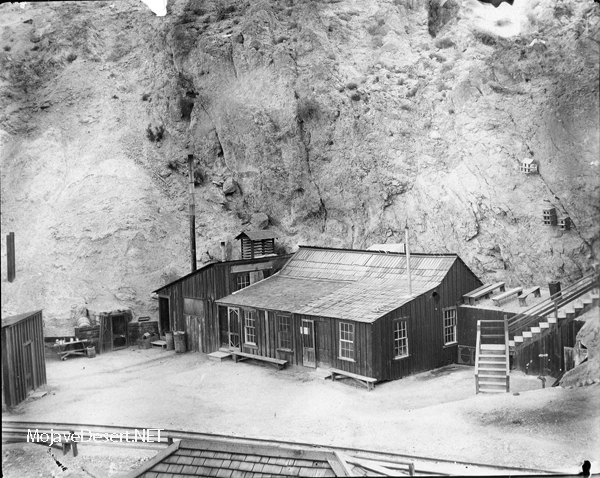

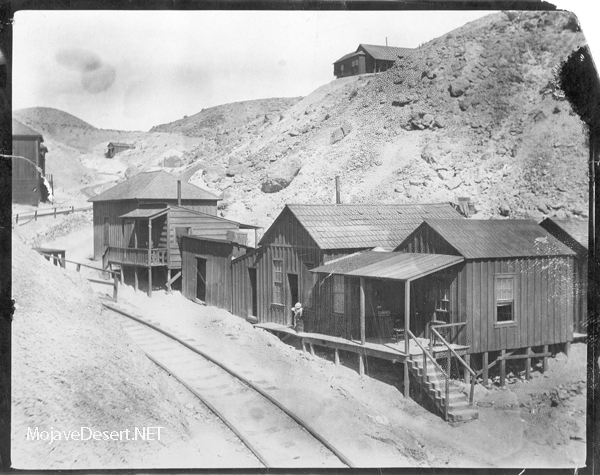

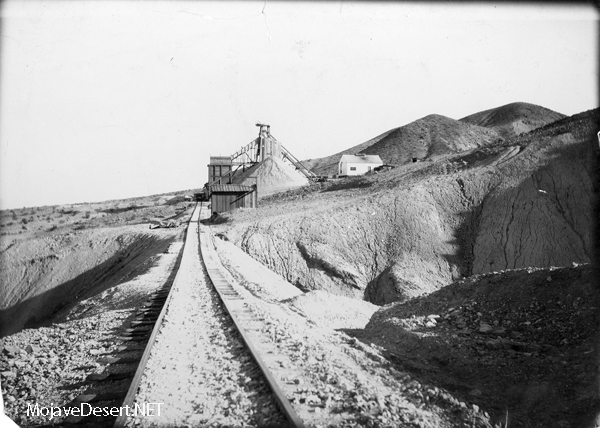

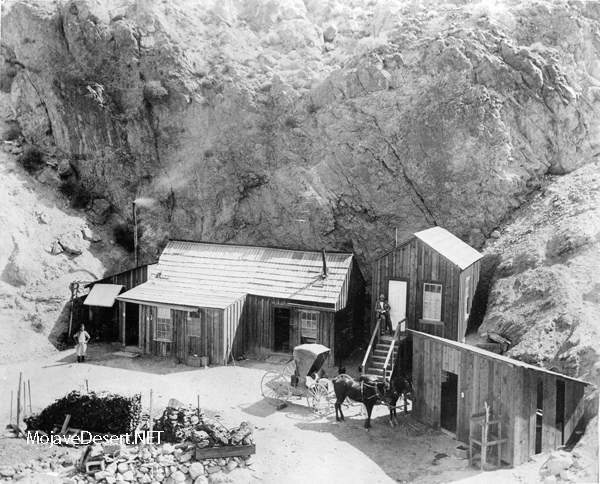

Borate Gallery

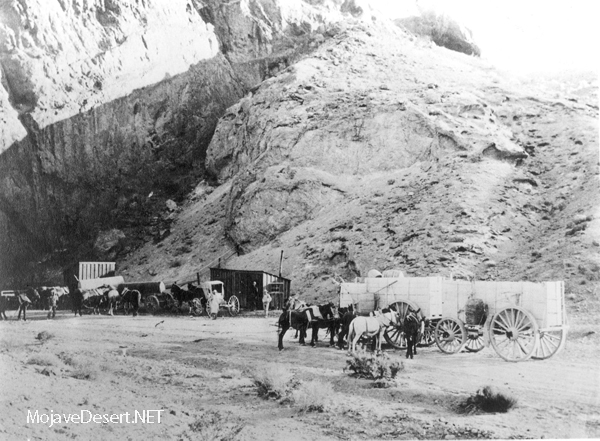

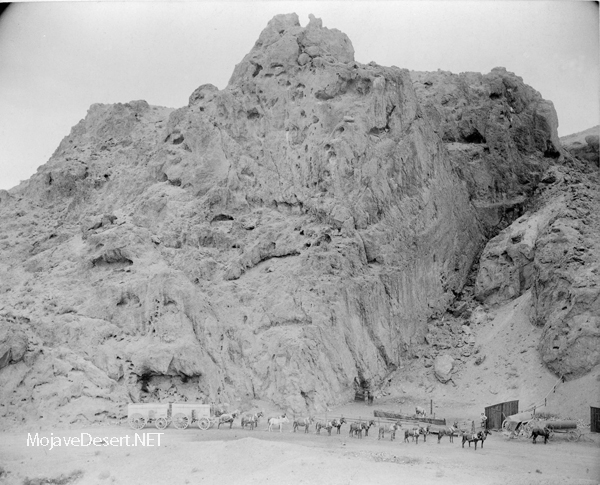

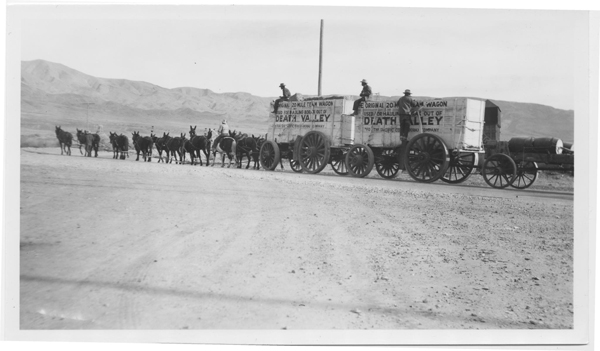

Borax mining in the United States started with the production of borax from Borax lake in Tehama County in 1864. The discovery of cotton ball ulexite in the playa of Teel’s Marsh by Frances Marion (Borax) Smith in 1872 ushered in the first major production of Borax in the United States. The center of cotton ball production then moved to Death Valley in 1880. The most famous operation was the Harmony borax works run by William Tell Coleman. This is the operation that becomes associated with the twenty-mule team wagons. With the discovery of colemanite, the Playa period started to decline.

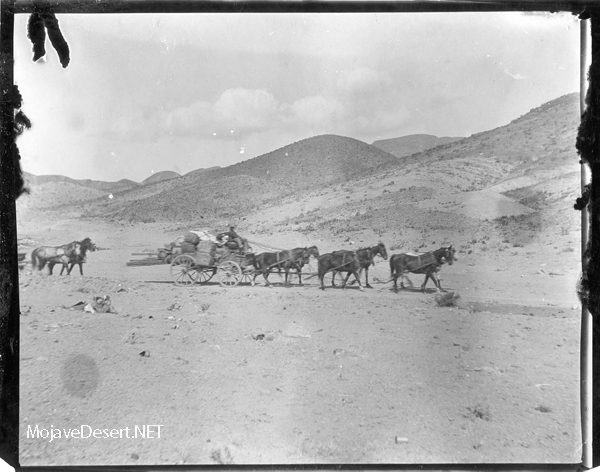

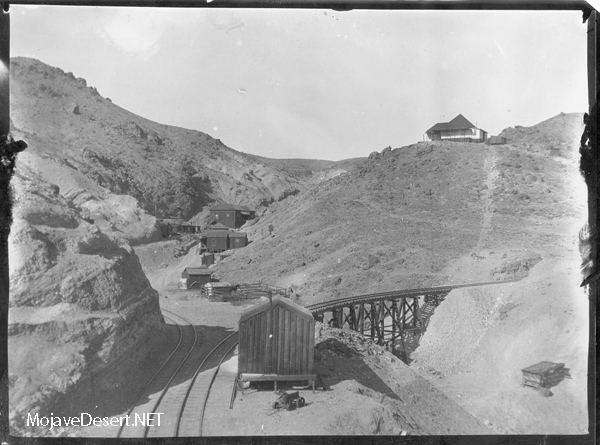

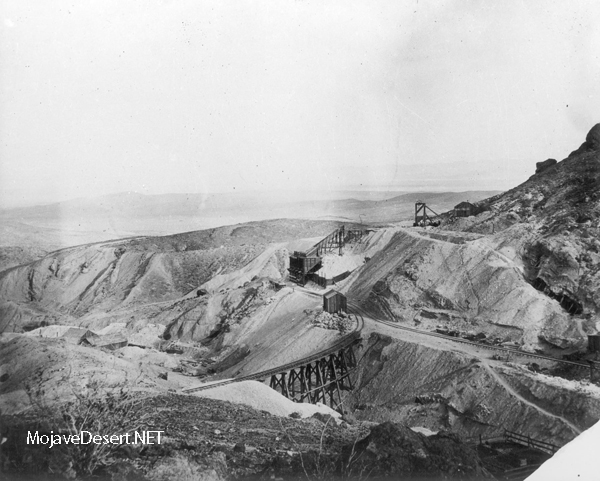

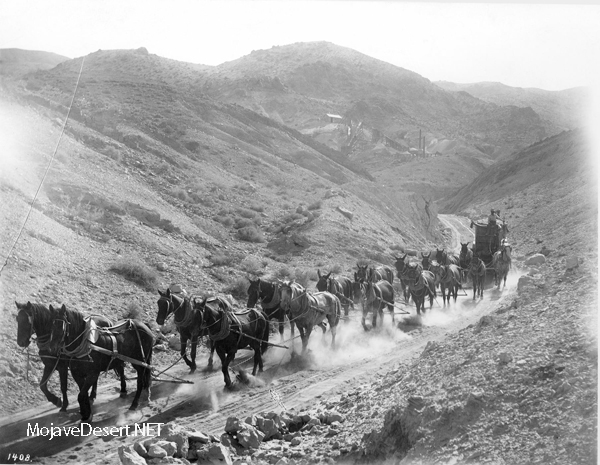

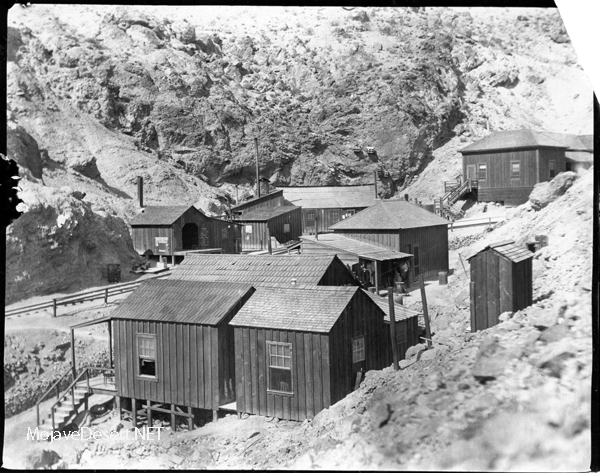

The mines at Borate ushered in the Colemanite period of borax production. W. T. Coleman initiated the mining operations at Borate in 1884, but actual production did not commence until 1890. Several factors contributed to this delay. The first was the obvious need to provide transportation to the area and develop the mines. The second was the bankruptcy of the “House of Coleman.” In 1890 Borax Smith acquired the property from Coleman’s creditors. He then formed the Pacific Coast Borax Company and commenced shipping ore to the recently updated refinery in Alameda, California.

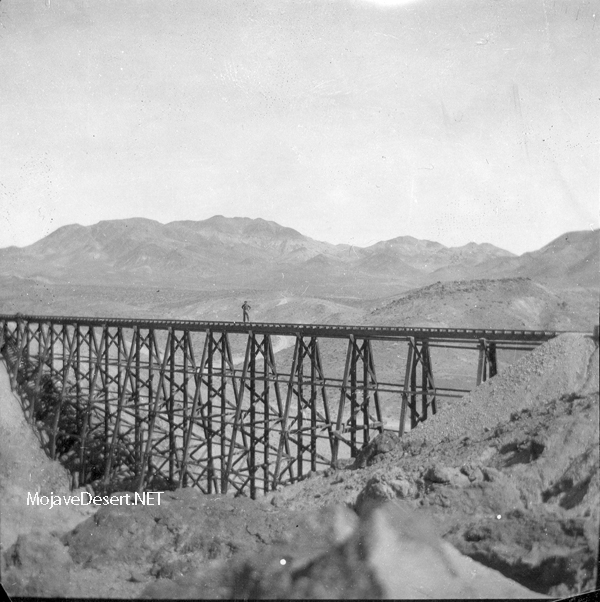

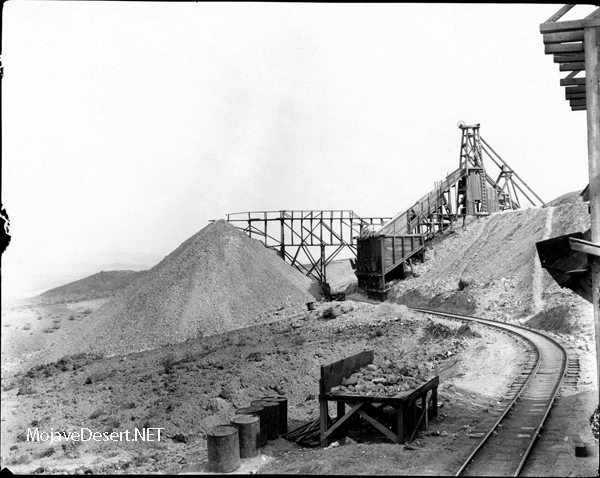

The two major problems plaguing production at Borate were the transportation and concentration of the ore. Initially, the ore was hand sorted at the mine and hauled to Daggett using the 20 mule teams and wagons once used in Death Valley. Smith was unhappy with this method, so in 1894 he experimented with a steam tractor locally called “Old Dinah.” Unfortunately, this experiment was a failure due to the nature of the road from the mines to Daggett. A narrow gauge railroad was then constructed in 1898 allowing the unprocessed ore to be shipped to a Calcining plant located at Marion, just North of Daggett. The ore was heated until the colemanite decrepitated and could be separated from the gangue. This allowed a better grade of ore to be shipped to Alameda and solved both problems.

By 1907 it was obvious to Smith that the days of Borate were numbered and the main operations were shifted to the Lila C mine at old Ryan, near Death Valley. All of the equipment, including the buildings, were removed and sent to the Lila C, leaving Borate completely bare. The Lila C lasted for only seven years and colemanite mining shifted to various mines in the Death Valley region. In 1927 the mines at Boron opened ushering in the Kernite period. Lessees and small miners continued operations at Borate until the opening of the mines at Boron.

text: http://wikimapia.org/1783734/Borate-CA-site