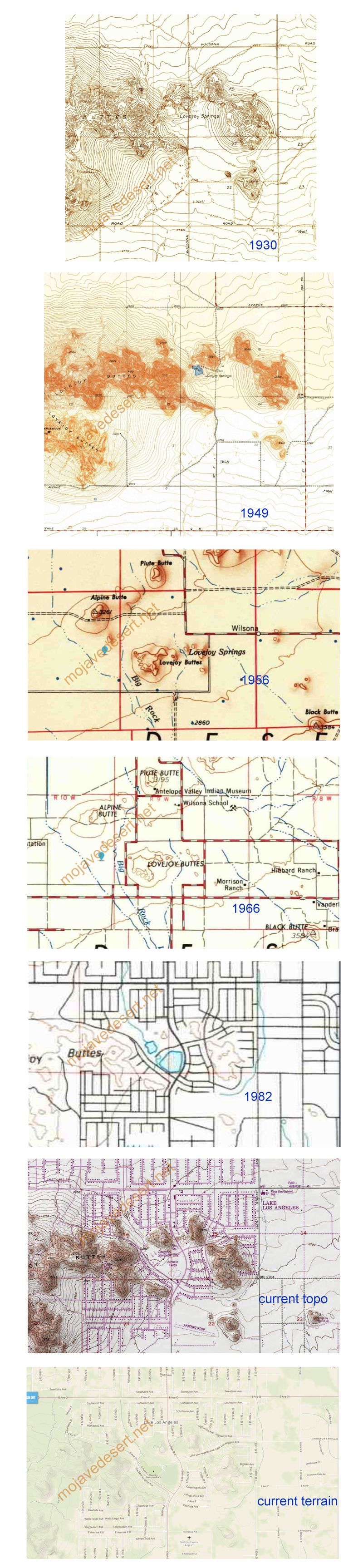

The Story of Lovejoy Springs becoming Lake Los Angeles, in maps …

/lake-los-angeles-ca/

The Story of Lovejoy Springs becoming Lake Los Angeles, in maps …

Nestled within the rugged landscapes of Eastern California, the Panamint Valley is home to a historical artery that has played a pivotal role in developing the American West—the road to Panamint. Originally trodden by Native Americans and later transformed by the ambitions of silver miners, this route not only facilitated economic booms but also bore witness to the ebbs and flows of fortune. The road to Panamint is a testament to the region’s mining era, epitomizing the broader transportation infrastructure development crucial for westward expansion.

The Panamint Valley, framed by the arid peaks of the Panamint Range, was first utilized by the Shoshone Native Americans, who traversed these harsh landscapes following seasonal migration patterns and trade routes. The discovery of silver in 1872 marked a turning point for the valley. News of silver attracted droves of prospectors, catalyzing the establishment of mining camps and the nascent stages of the road. This road would soon become the lifeline for a burgeoning settlement, later known as Panamint City.

The transformation from a series of Native trails to a fully functional road was propelled by the mining industry’s explosive growth. As prospectors and entrepreneurs flooded the area, the demand for a reliable transportation route skyrocketed. The road to Panamint was quickly carved out of the valley’s rugged terrain, facilitating the movement of people and ore. During the mid-1870s, Panamint City blossomed into a boomtown, with the road being crucial for transporting silver ore to markets beyond the valley. However, as the mines depleted and profits dwindled, the road witnessed the departure of those who had come seeking fortune, leaving behind ghost towns and tales of a fleeting era.

Beyond its economic contributions, the road to Panamint played a significant role in shaping the regional history of Eastern California. It facilitated the integration of remote areas into the state’s broader economic and cultural fabric. Moreover, it was a stage for several historical events, including conflicts between Native Americans and settlers and among competing mining companies. The road connected Panamint with the outside world and helped establish transportation routes that would later support the growth of other regional industries and settlements.

Today, the road to Panamint is a shadow of its former self, yet it remains an integral part of the cultural heritage of the American West. Efforts have been undertaken to preserve its historical significance, recognizing the road as a physical pathway and a historical document inscribed upon the landscape. It is featured in historical tours, providing insights into the challenges and triumphs of those who once traveled its length in pursuit of silver and survival. The preservation of this road allows contemporary visitors and historians alike to traverse the same paths miners once did, offering a tangible connection to the past.

The road to Panamint encapsulates the spirit of an era driven by the quest for precious metals and the relentless push toward the West. Its historical importance remains a key narrative in understanding how transportation helped shape the economic and cultural landscapes of the American West. As we reflect on its legacy, the road to Panamint continues to offer valuable lessons on resilience and the transient nature of human endeavors.

Chronology of Events

The 1785 Land Ordinance provided that all federal land would be surveyed into townships six miles square. Townships are subdivided into 36 one-mile-square sections. Sections can be further subdivided into quarter sections, quarter-quarter sections, or irregular government lots. Each township is identified with a township and range designation. Township designations indicate the location north or south of the baseline, and range designations indicate east or west of the Principal Meridian. A meridian is an imaginary line running north to south.

1861 Central Pacific Railroad is incorporated.

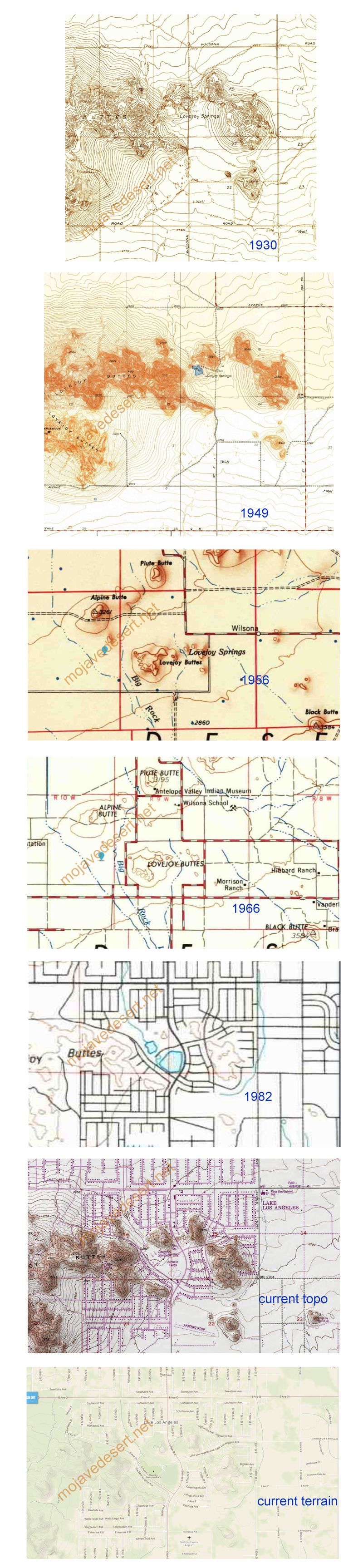

1862 President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act, a law that authorizes the federal government to give land grants and loans to aid construction of the Central Pacific Railroad as the Western part of the Transcontinental Railroad and the Union Pacific as the Eastern part.

1863 Central Pacific begins construction at Sacramento.

1864 The United States Congress passes the Pacific Railway Act of 1864, which doubles the land grant to 20 alternate sections per mile, with a 20 mile checkerboard corridor on each side of the right-of-way.

1865 The Southern Pacific Railroad Company is incorporated.

1865 Central Pacific Railroad establishes a Land Department in Sacramento. Benjamin B. Redding, former mayor of Sacramento, was chosen to lead to design and manage the new organization.

1866 The Pacific Railway Act is amended to allow a railroad to select lands outside of the land grant area in exchange for unavailable land grant land.

1866 The federal government gives Southern Pacific Railroad a land grant to complete the western section of the Atlantic & Pacific line through California via Mojave to Needles.

1867 First land patent is issued to the Central Pacific Railroad by the federal government.

1868 September 25: The Central Pacific Railway owners acquire control of the Southern Pacific Railroad.

1869 The California & Oregon Railroad receives a federal land grant to build a line northward from Davis to connect to the Oregon & California Railroad at the California and Oregon border.

1869 The Central Pacific Railroad begins operating the California & Oregon Railroad.

1869 The Golden Spike ceremony held at Promontory, Utah, marks the completion of the transcontinental railroad between Sacramento, California and Omaha, Nebraska.

1870 California & Oregon Railroad is consolidated with the Central Pacific Railroad, and becomes a branch line of the Central Pacific Railroad.

1871 The federal government gives the Southern Pacific Railroad land grants and loans, allowing it to build to meet the Texas & Pacific at Yuma, California and build from Los Angeles to Colton, California.

1875 The Southern Pacific Railroad opens a land agency in San Francisco. 1876 Jerome Madden, Benjamin Redding’s assistant, became the land agent for Southern Pacific.

1886 Southern Pacific Company assumes control of the Oregon & California Railroad.

1899 The Central Pacific Railroad is reorganized as the Central Pacific Railway in order to pay off its federal debt.

1912 The Southern Pacific Company transfers some of its remaining land assets to Southern Pacific Land Company.

1916 Oregon & California grant lands are returned to the Federal Government.

1927 Southern Pacific purchases the Oregon & California Railroad.

1984 The Southern Pacific Company merges with Santa Fe Industries, parent company of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, to form Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corporation (SPSF).

1985 The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) denies permission for the railroad operations to merge.

1986 Appeal of the ICC ruling fails.

1986 The renamed holding company, the Santa Fe Pacific Corporation, retains all of the non-rail interests of both companies except one. All of the Southern Pacific Railroad California real estate holdings are transferred to a new holding company, Catellus Development Corporation.

1996 The Southern Pacific Railroad is acquired by Union Pacific Railroad and its operations cease.

2005 Catellus Development Corporation is merged into ProLogis, another land development company based in San Francisco. ProLogis remains one of the largest real estate holders in California.

California State Railroad Museum Library and Archives

https://oac.cdlib.org/institutions/California+State+Railroad+Museum+Library+and+Archives

U.S. Highway 395, often simply referred to as Highway 395, is a north-south highway that runs through the western part of the country. It spans approximately 1,300 miles (2,092 kilometers) from southern California to the border of Washington and Canada.

Part of this highway passes through the Mojave Desert in California. The Mojave Desert is known for its arid landscape, unique geological features, and desert flora and fauna. Highway 395 offers travelers the opportunity to experience the beauty and solitude of the Mojave Desert while providing access to various points of interest along the way.

Here are some key points about U.S. Highway 395:

Some notable places and attractions along U.S. Highway 395 in the Mojave Desert region include:

Travelers along U.S. Highway 395 can experience the stark beauty of the Mojave Desert, explore its geological wonders, and access various outdoor recreational opportunities. It’s a popular route for road trips and exploration of California’s eastern Sierra region.

Overall, U.S. Highway 395 is a significant transportation corridor in the western United States, known for its stunning scenery, recreational opportunities, and historical significance. It offers travelers a chance to explore diverse landscapes and experience the beauty of the American West.

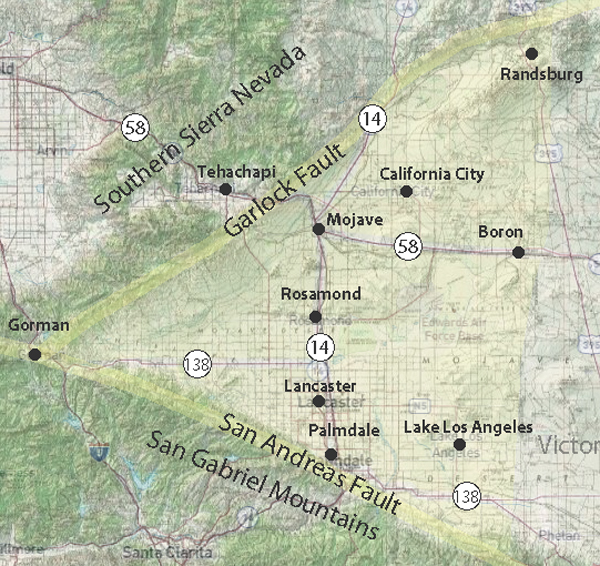

The Antelope Valley is a region located in northern Los Angeles County and southeastern Kern County in the state of California.

Here are some key geographical features and aspects of the Antelope Valley:

Understanding the geography of the Antelope Valley involves recognizing its desert setting, mountainous surroundings, urban centers, and economic activities.

Death Valley is part of the Mojave Desert. Death Valley is a desert valley located in Eastern California and a small part of Nevada in the United States. It is one of the hottest places on Earth and holds the record for the highest air temperature ever recorded, which reached 134 degrees Fahrenheit (56.7 degrees Celsius) in Furnace Creek Ranch on July 10, 1913.

The Mojave Desert is a vast desert in the southwestern United States, primarily in southeastern California, southern Nevada, and parts of Arizona and Utah. It is the driest desert in North America and is known for its arid landscapes, unique plant and animal life, and iconic features like Joshua Tree National Park.

Death Valley is situated within the Mojave Desert, and the two are often mentioned together due to their geographic proximity and shared arid climate characteristics.

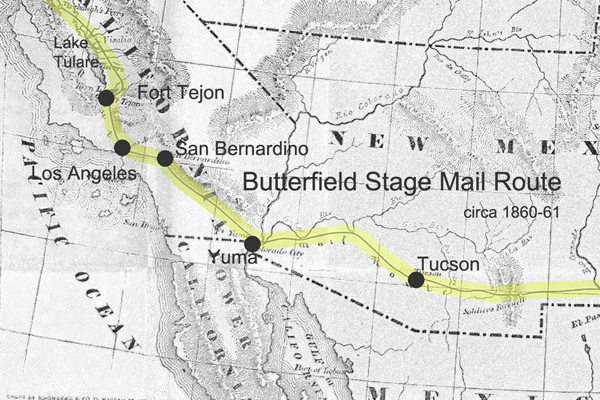

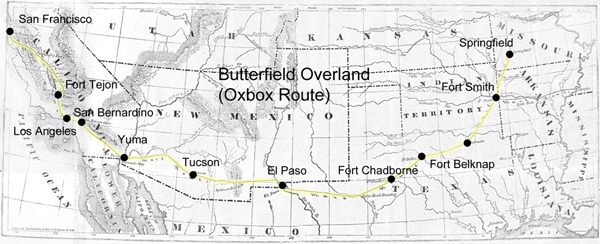

The Butterfield Overland Mail Route was a historic transportation route in the mid-19th century that played a crucial role in connecting the eastern and western parts of the United States.

Here are some key points about the Butterfield Overland Mail Route:

The Butterfield Overland Mail Route remains an important chapter in the history of westward expansion and transportation in the United States during the mid-19th century.

https://mojavedesert.net/stagecoaches/

https://mojavedesert.net/mojave-desert-indians/

https://digital-desert.com/historic-roads/

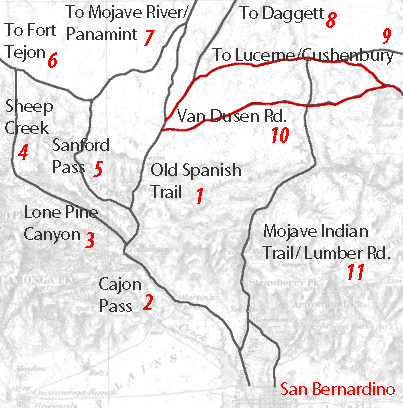

Cajon Pass/Victor Valley Roads

1 – Old Spanish Trail/Indian trail (1827)

2 – Cajon Pass (Lower) – Indian trail

3 – Lone Pine Canyon – Indian trail

4 – Sheep Creek – Indian trail

5 – Sanford Pass (c.1854-57)

6 – Fort Tejon – Indian trail

7 – to Mojave River – Indian trail

8 – to Daggett (c.1855)

9 – Lucerne/Cushenbury Lumber road

10 – Van Dusen/Holcomb Valley Road – (1862)

11 – Mojave Indian trail (c.1776, 1826)