A History of American Indians in California: HISTORIC SITES

Tejon Indian Reservation

Kern County

In the early 1800s, Indians in the interior of California began to feel the effects of trappers and explorers. By mid-century, coastal Indians who moved inland following the breakup of the missions also suffered under the influx of miners and settlers. When the federal government sent Indian agents to write treaties with California Indians, Agent George W. Barbour negotiated the treaties with both interior and coastal Indians in the southern San Joaquin Valley. In return for the promise of goods, annuities, and land, the Indians vacated much of their home land.

In February of 1852, President Millard Fillmore submitted 18 California Indian treaties to the United States Congress for ratification, but the California delegation objected, complaining that the treaties provided too much good land for the Indians. Congress failed to ratify the treaties but did make some provisions for California Indians.

Edward F. Beale was appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs for California in April 1852. Upon arrival in September, Beale toured the state to determine the status of California Indians. He reported in February 1853 that “our laws and policy with respect to Indians have been neglected or violated. . . . [The Indians] are driven from their homes and deprived of their hunting-grounds and fishing-waters at the discretion of the whites. . . .” Beale requested $500,000 for military reservations where both soldiers and Indians would reside.

Beale hired H. B. Edwards to start farming operations at Tejon and the San Joaquin River. On March 2, 1853, Congress appropriated $250,000 for five reservations, not to exceed 25,000 acres each, to be located on public lands, with good land, wood, and water. In September, Beale expanded the Tejon Farm into the first California reservation.

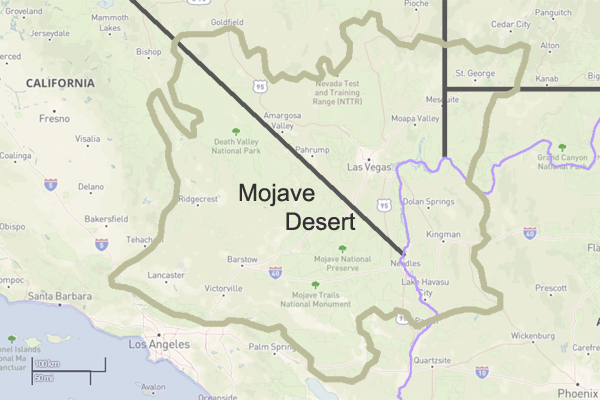

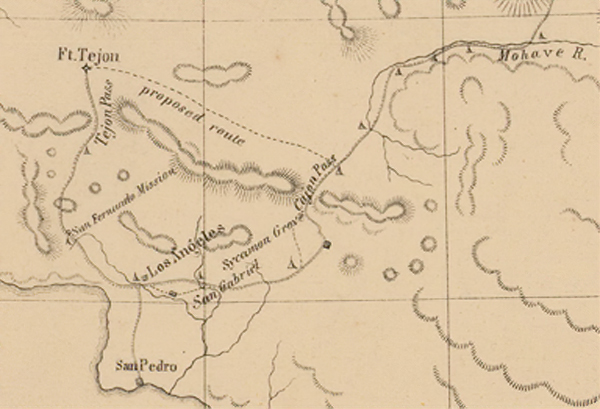

To gain support for his efforts, Beale named the reservation after Senator William Sebastian, Chairman of the Indian Affairs Committee. The Sebastian Indian Reservation, more commonly known as Tejon Indian Reservation, was located in the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley, “between Tejon Vaquero Headquarters and Canada de las Uvas. . . .” (Latta, 1977:736)

Tejon was located on a Mexican land grant rather than on public land, but Beale argued that no public lands were available and that the unoccupied grant could be purchased if necessary. Beale’s primary reason for choosing Tejon was the presence of mission-trained Indians with agricultural skills, more likely to succeed on a reservation.

Despite substantial opposition, Beale continued to gather Indians and move them to Tejon. In early 1854, he reported 2,500 Indians at Tejon and 2,650 acres under cultivation. Beale’s arguments for a reservation of 75,000 acres failed, and in July 1854, he was replaced by Thomas J. Henley.

When Henley took charge, he noted only 800 Indians, with fewer than 350 present at one time, and only 1,500 acres under cultivation, indicating that numbers of Indians and amount of acreage under cultivation had been inflated. Most of the crops failed that year because of drought. Henley started the Tule River Farm to supplement the reservation’s food, but the Indians still had to gather native foods and the government had to bring in more supplies in order to feed the reservation population. Throughout the reservation’s existence, drought, insects, and crop disease undermined the attempts at farming.

In November of 1856, the reservation was reduced to 25,000 acres. That year, 700 Indians were reported residing on the reservation and 700 acres were under cultivation. By 1859, Henley had been replaced.

In addition to crop failure, the reservation faced loss of the land when the land grant claim was upheld in court. Settlers also encroached on the unsurveyed and unfenced land, allowing cattle and sheep to eat reservation crops. During the 1863 drought year, all the crops were lost except for 30 tons of hay.

Meanwhile, former agent Edward F. Beale had purchased five contiguous ranchos in the Tejon area, including the reservation land, and was raising 100,000 sheep. In 1863, he offered to lease 12,000 acres to the government for a dollar an acre, but withdrew the offer when he found that the government planned to move Owens River Indians there. He noted that he had made the offer only because Indians already on the reservation were his friends.

Jose Pacheco, a Tejon leader, wrote to General Wright on April 16, 1864, “I should not have troubled you with this letter, Dear General, did I not think the agents here had wronged us. You and our great father at Washington do not know how bad we fare, or you would give us food or let us go back to our lands where we can get plenty of fish and game. I do not think we get the provisions intended for us by our Great Father; the agents keep it from us, and sell it to make themselves rich, while we and our children are very poor and hungry and naked.” (Sacramento Union, April 28, 1964)

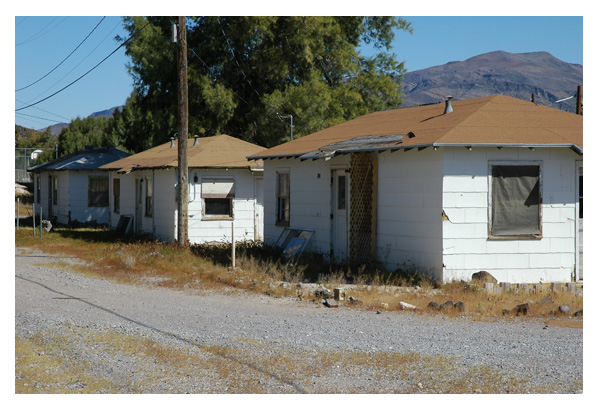

The reservation was ordered closed in June 1864, and on July 11, Austin Wiley wrote, “I have the honor to inform you that all the Indians on the Tejon Farm and in the vicinity of Fort Tejon, some two hundred in number, have been removed from there to the Tule River farm.” Wiley noted that there was no food for the Indians at Tejon.

Shortly thereafter, D. N. Cooley, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, summarized the reasons for the reservation’s failure: “The lack of legal title to the land severely restrained investment in construction and development, leaving the reserve and the Indians on it in a state of constant uncertainty. The ideal of converting Indians from food gathering to settled agriculture was never realized.”

(Note: Unless otherwise specified, all above quotes are from government reports as cited in California Department of Parks and Recreation reference document No. 169, “Tejon Indian Reservation.”)

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/5views/5views1h92.htm