History of Kern County, California (Wallace M. Morgan, 1914):

Pre-1850s

- Native Yokuts and Serrano tribes inhabit the region, living along rivers and valleys, practicing hunting and gathering.

- Lieutenant Edward F. Beale later establishes the Tejon Reservation to “civilize” and protect these groups.

1849

- Naturalist John Audubon travels through the area, recording early observations of wildlife and the potential for settlement.

1851

- First discovery of gold along the Kern River sparks a regional rush.

- Miners arrive from southern and northern routes, establishing primitive camps.

1852–1854

- Quartz mining begins at Keysville; the Keys and Mammoth Mines become notable operations.

- The first quartz mill is hauled from San Francisco.

- Mining towns like Whiskey Flat and Kernville emerge.

- Discovery of the Keys Mine in 1854.

1857

- California legislature passes a reclamation act for swamp and overflow lands.

- Early settlers, including Colonel Thomas Baker, began reclaiming the Kern Delta.

- A major flood reshapes portions of the lower Kern River lands.

1859

- The site of modern Bakersfield is first identified.

- Early cattlemen and settlers began to locate along the delta.

1860s

- Havilah was founded as a mining center and later became the first county seat.

- Immigrant roads and stage lines cross the valley.

- Floods of 1867–68 create temporary lakes and swamps; drainage projects follow.

- Early schools and cotton crops were established.

- Outlaw Tiburcio Vasquez operates in the region; wild-horse catching is common.

1866–1870

- Transition from placer mining to agriculture and stock raising.

- Swamp land patents granted to Baker and others.

- Ranching and sheep industries expand.

1868–1872

- Kern County formally created from parts of Tulare and Los Angeles counties.

- County seat at Havilah; first county officials elected.

- Colonel Baker becomes prominent in reclamation and civic improvement.

- 1872: Death of Colonel Thomas Baker, widely regarded as the founder of Bakersfield.

1873–1876

- Bakersfield wins the county seat election (1874).

- Town incorporated (1873) and disincorporated (1876).

- Havilah declines; Bakersfield begins steady growth.

- Early capitalists such as Livermore and Redington invest in local enterprises.

1877

- Severe drought devastates the county’s cattle and farming interests.

- Settlement expands in Tehachapi; first apple orchards planted.

1878–1885

- Water rights disputes intensify between Haggin, Carr, Miller & Lux.

- Major court cases begin over Kern River usage.

- Construction of irrigation ditches and canal systems begins.

- Early colonization efforts launched.

1880s

- Tehachapi develops as a railroad and agricultural community.

- Lynchings and outlaw conflicts occur during this rough period.

- Bakersfield experiences a fire and rebuilding effort.

- Introduction of electricity and other public utilities.

1890–1895

- Mining resurgence: discovery of the Yellow Aster Mine at Randsburg.

- Other desert mining districts (Amalie, Tungsten) discovered.

- Bakersfield gains street railways and gas/electric utilities.

- Great railway strike affects local commerce (1894).

1899

- Discovery of oil near McKittrick and Sunset; first wells drilled.

- Beginning of Kern County’s modern oil era.

1900–1905

- Kern River oil field developed; Elwood brothers credited with major discovery.

- Early pipelines and refineries built.

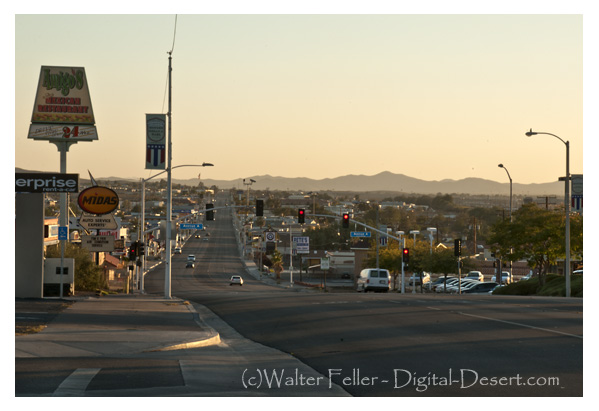

- Bakersfield begins paving, civic expansion, and population growth.

1906–1910

- Lakeview gusher (1910) becomes one of California’s largest oil strikes.

- Consolidated Midway and North Midway fields expand.

- Gushers flood markets; oil regulation and conservation efforts start.

- Bakersfield experiences building boom; new roads and public buildings constructed.

1911–1913

- Pump irrigation develops in valley towns like Wasco and McFarland.

- Citrus and apple industries expand.

- Bakersfield and Kern consolidate as one municipality.

- Bonds issued for paved roads and infrastructure.

- County churches, schools, and civic institutions flourish.

1914

- Publication of Morgan’s History of Kern County marks the county’s transition from frontier to industrial modernity.

- Bakersfield stands as the regional center of oil, agriculture, and commerce.