/zzyzx/

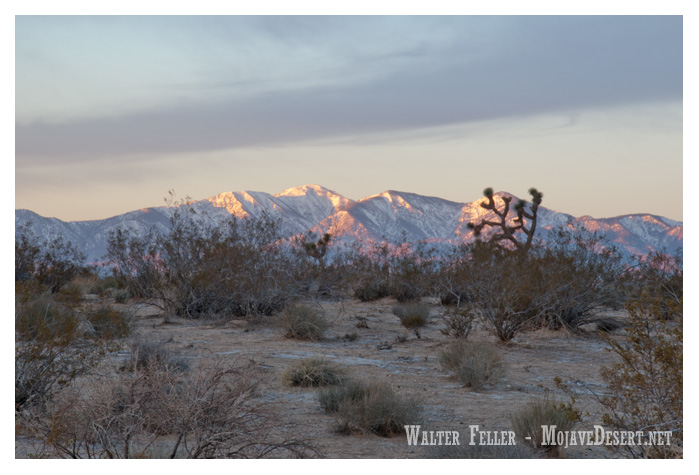

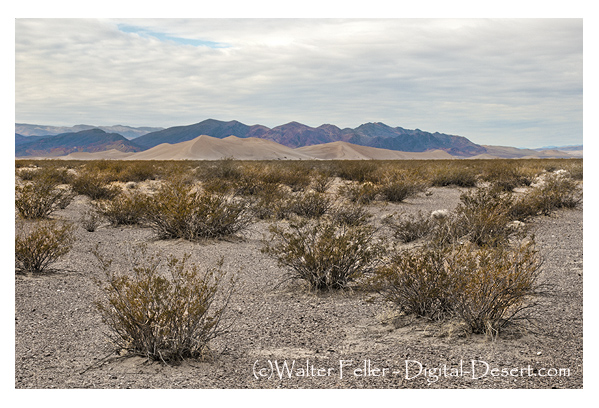

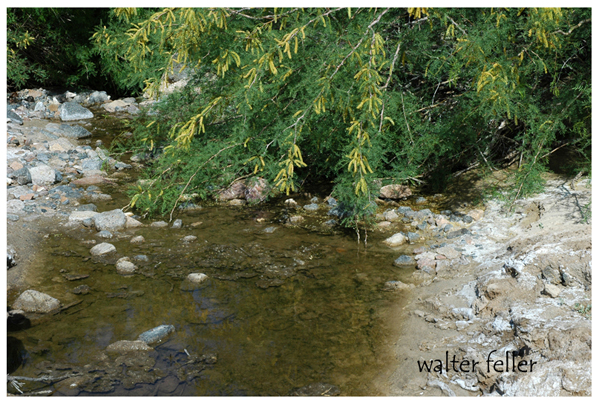

Zzyzx, pronounced “zy-zicks,” is a unique and intriguing place in the Mojave Desert of Southern California, USA. Specifically, it is home to the Desert Studies Center, operated by the California State University (CSU) system. The center serves as a field station for research and education focused on the desert ecosystem.

Here are some key points about Zzyzx and the Desert Studies Center:

- Location: Zzyzx is approximately 100 miles northeast of Los Angeles, near Baker, California. The Desert Studies Center is part of the larger California State University system and is used for academic and research purposes.

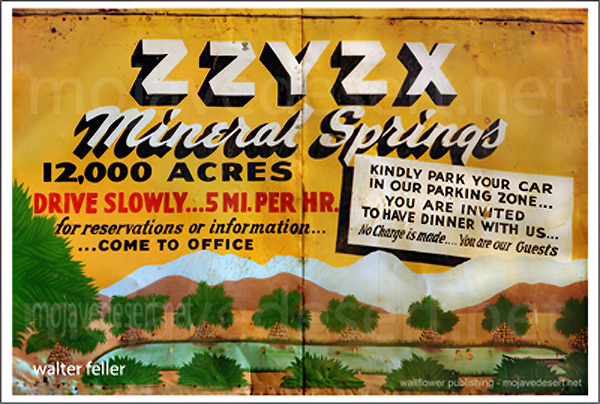

- History: The name “Zzyzx” was given to the area by Curtis Howe Springer, a self-proclaimed medical doctor and radio evangelist who established the Zzyzx Mineral Springs and Health Spa in the 1940s. The name was created to be the last word in English, and Springer intended to use it for marketing purposes. However, in 1974, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) reclaimed the land, and it became the site for the Desert Studies Center.

- Desert Studies Center: The Desert Studies Center is a research and educational facility jointly operated by the California State University system. It provides a base for researchers, students, and educators interested in studying the unique ecology and geology of the Mojave Desert. The center offers facilities for field courses, workshops, and research projects related to desert studies.

- Facilities: The Desert Studies Center has dormitories, classrooms, laboratories, and other amenities to support researchers and students. It serves as a hub for scientific exploration and learning about the challenges and adaptations of life in desert environments.

- Research: Researchers at the Desert Studies Center focus on various topics, including desert ecology, geology, climate, and biodiversity. The unique characteristics of the Mojave Desert make it an ideal location for studying desert ecosystems and understanding how plants, animals, and microorganisms have adapted to this arid environment.

Visitors to the Desert Studies Center can explore the surrounding Mojave Desert, learn about its flora and fauna, and gain insights into the challenges and opportunities presented by desert ecosystems. It’s a valuable resource for those interested in environmental science, ecology, and desert studies.