/mastodon-mine/

The Mastodon Mine in Joshua Tree National Park has history dates back to the early 20th century. In southeastern California, Joshua Tree National Park is renowned for its stunning desert landscapes, unique vegetation, and geological features.

The Mastodon Mine was primarily a gold mine, reflecting the broader gold mining activity of the California Gold Rush era. However, it occurred later than the initial rush of 1849. Mining in this region was fueled by the discovery of gold and the potential for profitable mining operations.

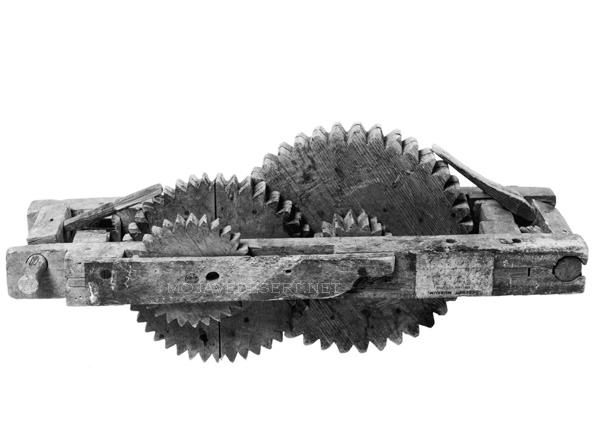

The mine was established in the early 1900s. The Mastodon Mine was not one of the region’s largest or most productive mines during its operational years. Still, it was significant enough to draw workers and contribute to the local mining history. The miners would have used traditional hard-rock mining techniques to extract gold from the quartz veins in the area.

Over the years, the mine changed hands and eventually ceased operations. Like many abandoned mines, it was left with remnants of its mining past, including shafts, tunnels, and debris. These remnants are historical artifacts, providing insight into the mining techniques and life during that period.

In 1994, the area encompassing the Mastodon Mine became part of Joshua Tree National Park, established to protect the region’s unique desert ecosystem and cultural heritage. The National Park Service manages the site, balancing preserving historical resources with protecting the natural environment.

Today, the Mastodon Mine is a point of interest for Joshua Tree National Park visitors. It offers a glimpse into the area’s mining history, with trails leading to the mine site and interpretive signs providing information about its history and impact on the region.

As with many historical sites, the information about the Mastodon Mine is based on historical records, archaeological evidence, and ongoing research. The National Park Service and historians continue to study such sites to understand the region’s past better.