The California Southern Railroad was a critical 1880s project that connected Southern California to the transcontinental rail network. Backed by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway, it built a line from San Diego northward through San Bernardino and the Cajon Pass to reach the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad at Barstow. This report chronicles the railroad’s planning and surveying, its phased construction timeline, the engineering challenges of Cajon Pass, key figures involved, construction methods, conflicts encountered, and the line’s integration into the Santa Fe system and impact on the region.

Background and Planning

In the late 1870s, San Diego businessmen – notably Frank Kimball – were desperate to end the city’s isolation by rail. After failing to interest tycoons like Jay Gould or Collis Huntington, Kimball courted the Santa Fe leadership with incentives, including land grants around San Diego. The Santa Fe saw an opportunity to break Southern Pacific’s monopoly in California and agreed to support a new subsidiary line via San Bernardino. Thus, the California Southern Railroad was incorporated on October 16, 1880, with Santa Fe officers (led by President Thomas Nickerson) on its board. The plan was to build 116 miles from San Diego to San Bernardino by mid-1882, where it would link up with Santa Fe’s transcontinental partner, the Atlantic & Pacific (A&P) Railway. This ambitious scheme set the stage for a difficult but historic construction effort through some of California’s most challenging terrain.

Construction Timeline (1880–1885)

Construction of the California Southern proceeded in two major phases: Phase 1, from San Diego to San Bernardino (via Colton), and Phase 2, from San Bernardino through the Cajon Pass to Barstow. Below is a timeline of key construction milestones and setbacks:

- October 1880 – Groundbreaking: The railroad’s Chief Engineer, Joseph Osgood, established headquarters in San Diego on October 11, 1880, marking the unofficial start of construction. With Santa Fe financing and local land grants secured, grading and tracklaying began northward from National City (San Diego’s port terminus).

- January 1882 – Reaching Oceanside/Fallbrook: By January 2, 1882, crews had laid about 55 miles of track, reaching Fallbrook Junction in northern San Diego County. The line hugged the coast through Oceanside, then turned inland up the Santa Margarita River valley, requiring many bridge crossings in Temecula Canyon, a gorge with sheer rock cliffs.

- August 1882 – Arrival at Colton: Construction pressed on through Riverside County, and by August 16, 1882, tracks reached Colton, just shy of San Bernardino. Here, the California Southern confronted the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP), which vehemently opposed any crossing of its tracks. SP officials even parked a locomotive on the proposed crossing point to obstruct the crew. A legal battle ensued; ultimately, California’s governor (Robert Waterman) ordered the local sheriff to enforce a court injunction, compelling SP to allow the crossing. With the blockage removed, the California Southern built a diamond crossing over SP’s line at Colton.

- September 1883 – Line Opens to San Bernardino: The first California Southern train triumphantly steamed into San Bernardino on September 13, 1883. San Bernardino, having been founded as a Mormon colony decades earlier, welcomed the new competition to SP’s rail monopoly. The completed San Diego–San Bernardino segment (via Temecula Canyon) formed part of Santa Fe’s “Second Transcontinental” route, albeit still disconnected from the A&P mainline in the Mojave Desert.

- Winter 1884 – Catastrophic Floods: Disaster struck just months later. In February 1884, torrential rains turned the Santa Margarita and Temecula creeks into raging torrents. Floodwaters obliterated about 8 miles of track in Temecula Canyon, washing away trestles and roadbed – with rails and timbers reportedly floating out to sea. The damage, estimated at $319,000, far exceeded the cash-strapped railroad’s means. Service on the line was completely halted for nine months while crews struggled to make repairs. By January 6, 1885, the route was finally reopened to traffic after extensive rebuilding.

- Late 1884 – Santa Fe Takeover: The 1884 flood crisis left the California Southern on the brink of bankruptcy. Fearing the line might fall into rival hands, Santa Fe’s President William Barstow Strong moved decisively to absorb the company. In October 1884, the AT&SF acquired a controlling interest in the California Southern through a stock swap and also negotiated the purchase of Southern Pacific’s Mojave-to-Needles branch line (which ran via Barstow). These moves ensured Santa Fe’s full control of the San Diego–Barstow project and secured the route to the East via Barstow/Needles.

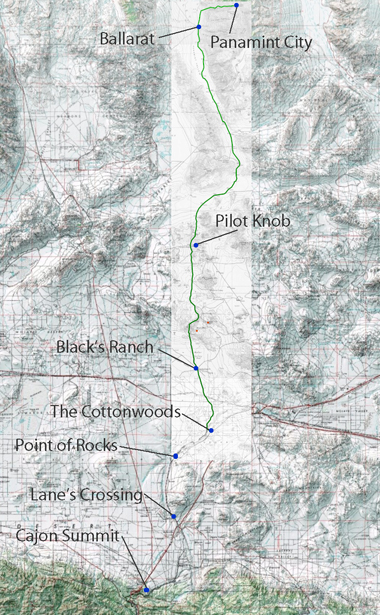

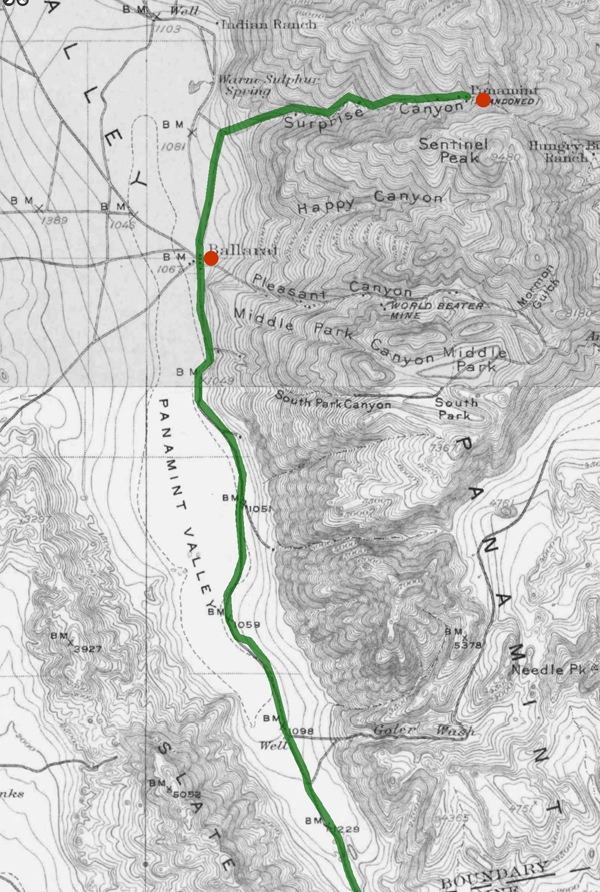

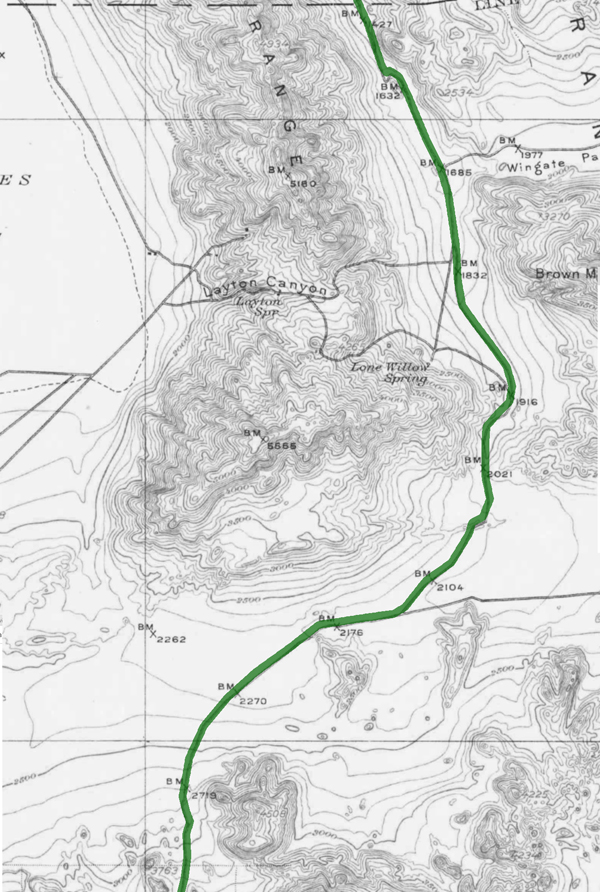

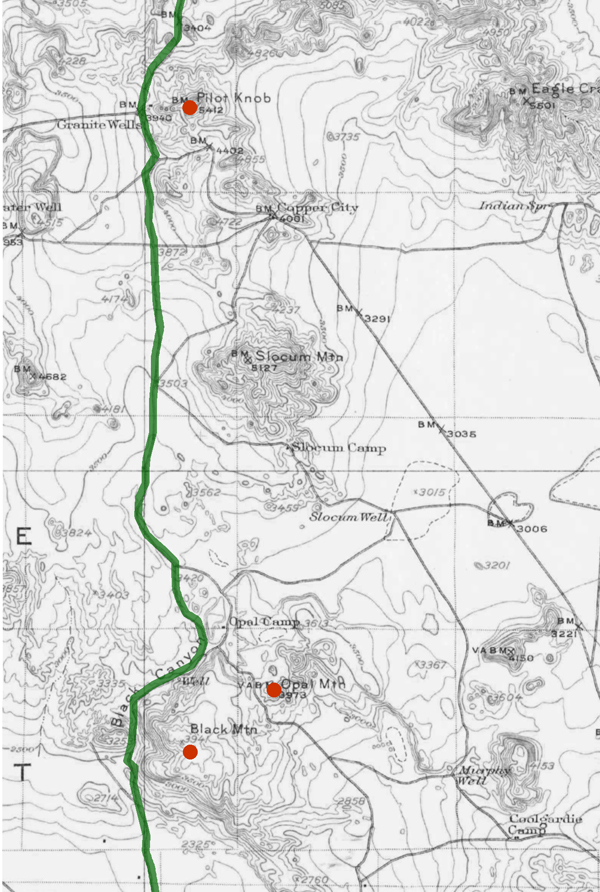

- 1885 – Building Through Cajon Pass: With finances and leadership now backed by Santa Fe, the final 81-mile gap from San Bernardino through Cajon Pass to Barstow was tackled in 1885. Santa Fe’s locating engineer, William Raymond “Ray” Morley, and local chief engineer Fred T. Perris led surveying parties to plot a feasible ascent through the San Bernardino Mountains. Construction crews attacked the pass from both ends – working northward from San Bernardino and southward from the Barstow area (then called Waterman).

- November 1885 – Completion of the Line: On November 15, 1885, the last spike was driven in Cajon Pass, marking the completion of the California Southern Railroad and a continuous rail link from San Diego to the transcontinental mainline. Within a day, the first through passenger trains ran between San Diego and Chicago (via Barstow), establishing a second Pacific coast connection in competition with the Southern Pacific. The once-isolated San Diego now had rail access to the rest of the country.

Surveying and Engineering Challenges in Cajon Pass

Surveying a railroad through Cajon Pass – the cleft between the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountain ranges – posed formidable engineering challenges. The pass, created by the San Andreas Fault, is a naturally rugged corridor filled with steep grades and unstable geology. Chief Engineer Fred T. Perris and surveyor Ray Morley scouted the route in 1885, seeking a path that locomotives of the era could climb. They managed to keep the maximum grade to 3.4% on the eastbound (uphill) tracks to Cajon Summit at an elevation of 3,823 feet. This roughly 1,000-foot ascent from the base of the pass was achieved by tracing winding curves along the canyon walls, avoiding any single, overly steep incline. Early surveys had to balance the line’s curvature and grade: too sharp a curve or too heavy a grade would prevent trains from safely traversing the pass.

Complicating matters, the terrain through Cajon consists of fractured rock and sandy washes prone to erosion, a legacy of the fault line. Unlike easier routes, there was no gentle river valley to follow – only dry canyons and slopes. Morley and Perris chose to contour along natural benches and cut into hillsides, minimizing the need for expensive tunneling or switchbacks. (In fact, the original 1885 line included no significant tunnels; only in 1913, during a double-tracking project, were two short tunnels added – later “daylighted” in modern times.) The surveying team had to find stable ground for the railbed and design ample drainage to protect against flash floods in the desert gullies. The result was a sinuous route featuring famous curves (like Sullivan’s Curve) that allowed trains to gain altitude gradually. The achievement was considered one of Santa Fe’s great engineering feats of the 1880s, creating a viable railroad through a region previously deemed too rugged for rail travel.

Elsewhere along the route, natural obstacles also tested the engineers. South of San Bernardino, the line’s earlier segment through Temecula Canyon had demanded seven miles of roadbed chiseled through almost perpendicular rock cliffs. There, the railroad crisscrossed the Santa Margarita River numerous times on low wooden bridges – an engineering necessity that unfortunately exposed the line to destruction by floods. One Chinese laborer working in the sweltering Temecula gorge reputedly quipped that it was “all the same hellee, you bet,” referring to the hellish difficulty of the work. That experience underscored the need for solid engineering in Cajon Pass. Learning from prior washouts, the builders in Cajon placed bridges and culverts to carry ephemeral streams under the track and built up embankments to elevate the line in flood-prone areas. Still, steep mountain topography and seismic geology made Cajon Pass a supreme test of the railroad’s surveyors and graders, one that Perris and his team met with grit and ingenuity.

Construction Methods and Workforce

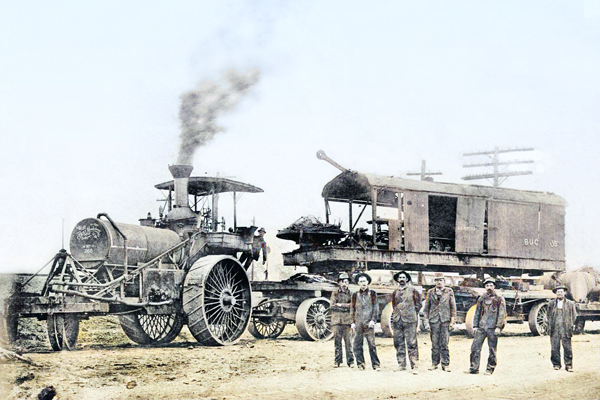

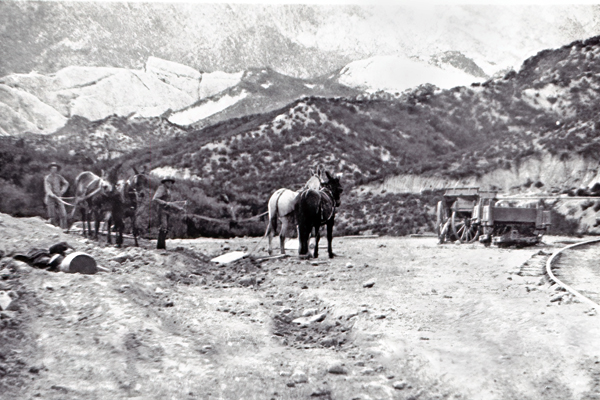

Building the California Southern Railroad in the 1880s required massive manual effort and traditional construction techniques. The project had no heavy machinery as we know it today – construction was essentially by hand labor with picks, shovels, horse-drawn scrapers, and black-powder explosives for blasting rock. The workforce swelled to thousands; in fact, over 6,000 laborers were employed at one point to push the line through Cajon Pass and down into Los Angeles. Chinese and Mexican immigrant laborers made up a large portion of the crews, especially on the hard sections through canyons and desert. These workers cleared brush, graded hillsides, dug cuttings, and built fills with wheelbarrows and dump carts. For rock cuts, crews drilled holes by hand or with rudimentary pneumatic drills, filled them with black powder, and blasted through obstacles. Timber was cut for trestle bridges and culverts, which were assembled on-site to span washes and rivers.

Material supply was an enormous logistical challenge for this railroad. San Diego had no existing rail connection in 1880, so every piece of rail, hardware, and rolling stock had to be shipped. Rails and fastenings were sourced from Belgium and Germany, loaded onto sailing ships, and carried around Cape Horn to San Diego’s port. The first load of steel rail arrived in March 1881 aboard the British ship Trafalgar, delivering the metal needed to push the line northward. Wooden ties (sleepers) were likely procured from Pacific Coast forests and brought by coastal schooners. At the railhead, workers practiced the standard tracklaying method of the era: teams of men known as “iron men” would lift rails into place with tongs, while others spiked them to the ties and gauged the track. Progress could reach several miles of track laid per day on flat ground, but slowed to a crawl in difficult terrain.

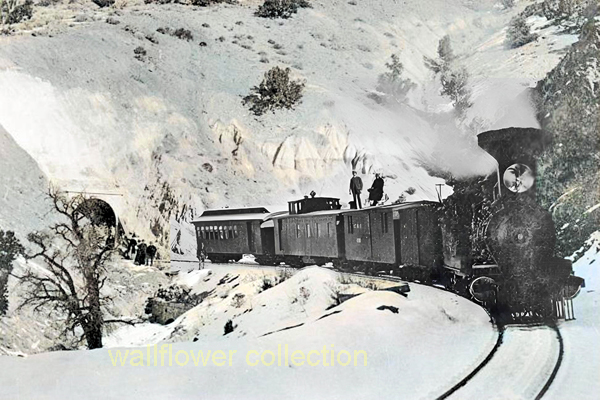

In Cajon Pass, construction methods had to adapt to the steep grades. Cuts and fills were carefully engineered: material from cuts was used to build up fills around curves, a balancing act that reduced how far debris had to be hauled. In some areas, temporary inclines and switchbacks were used to move construction equipment (such as small work locomotives) until the permanent grade was ready. Photographic evidence from the 1880s shows work trains carrying supplies up partially completed grades, and construction camps housing hundreds of workers in tent cities along the route. Despite the crude methods, the crews in Cajon Pass succeeded in laying a robust track. When the last rail was spiked down in November 1885, the California Southern’s construction legacy was one of dogged persistence with picks and shovels, achieving a task many thought impossible.

Key Personnel and Leadership

Several key figures were instrumental in the design, surveying, and construction of the California Southern Railroad’s route through Cajon Pass:

- Fred T. Perris – Chief Engineer: A British-born surveyor who settled in San Bernardino, Frederick T. Perris served as Chief Engineer of the California Southern (and later the Santa Fe). Perris personally directed the location surveys through Cajon Pass in 1885 and oversaw the construction of this last leg of Santa Fe’s second transcontinental route. The difficult passage through Cajon (often mis-called “El Cajon Pass”) was his crowning achievement, and the city of Perris, California (originally a railroad camp on the line) was named in his honor.

- William Barstow Strong – Santa Fe President: W.B. Strong was the AT&SF Railway’s president during the 1880s and the strategic mind behind the push into Southern California. He outmaneuvered Southern Pacific’s Collis Huntington to break the rail monopoly and spearheaded the Santa Fe’s support of the California Southern project. Strong authorized the heavy investment to rebuild after the 1884 floods and to conquer Cajon Pass, and Barstow (originally “Waterman Junction”) was later renamed in his honor once the line was complete.

- William Raymond “Ray” Morley – Chief Location Engineer: Ray Morley was a civil engineer for Santa Fe who had previously surveyed challenging mountain routes (his father surveyed Raton Pass in New Mexico). Morley partnered with Perris to plot the Cajon Pass alignment. His expertise in mountain railroading helped find a path with acceptable curvature and grade through Cajon’s canyons. Morley’s survey work ensured the railroad could be built without resorting to impractical solutions; he is credited with successfully locating the line.

- Frank Kimball – San Diego Advocate: Frank Kimball was not an engineer but rather a San Diego land developer whose vision and persistence were crucial in launching the railroad. He lobbied Eastern financiers and offered land from his Rancho de la Nación to entice the Santa Fe to back the line Kimball’s efforts paid off—he secured 10,000 acres in land grants and other concessions for the railroad, directly leading to the California Southern’s incorporation. He is often regarded as the “father” of the project, ensuring San Diego would finally get a transcontinental link.

- Joseph O. Osgood – Initial Chief Engineer: Joseph Osgood was the California Southern’s chief engineer at the outset of construction. He organized the surveying parties in 1880 and established the construction headquarters in San Diego. Under Osgood’s supervision, the first 70 miles of track were built from National City to Colton. He resigned before the Cajon Pass phase (with Perris taking over), but his groundwork from 1880–1882 laid the foundation for the line’s eventual success.

(Many others contributed, including hundreds of anonymous labor foremen, as well as contractors for grading and bridge building. Governor Robert Waterman and Sheriff J.B. Burkhart also played a memorable role by enforcing the law against Southern Pacific’s interference at Colton. But the figures above stand out as the principal players in getting the railroad built.)

Conflicts and Community Interactions

From its inception, the California Southern Railroad faced determined resistance from the entrenched Southern Pacific Railroad (SP), which jealously guarded its dominance in California. The most dramatic conflict occurred at Colton Crossing in 1882–1883. As California Southern crews prepared to lay track across SP’s north-south line, SP’s agents literally blocked the crossing with a locomotive and railcar, moving them back and forth to prevent any grade crossing construction. This showdown, known as the “Battle of Colton,” escalated until a court ordered SP to cease obstruction. When SP initially ignored the order, Governor Waterman dispatched the San Bernardino County Sheriff and militia to enforce it. Under this pressure, Collis Huntington’s SP capitulated, allowing the crossing to be completed. The successful crossing at Colton opened the way for the Santa Fe affiliate to enter San Bernardino, much to the delight of residents who had felt bullied by SP’s monopoly. The arrival of the first California Southern train in San Bernardino in 1883 was met with celebration – a vindication of the community’s support for a second railroad.

Local communities along the route mostly welcomed the railroad and the economic opportunities it promised. Towns like Oceanside, Riverside, and San Bernardino saw immediate benefits in freight and passenger service. New townsites sprang up as well – Pinacate (in Riverside County) was a railroad camp that evolved into the town of Perris (named after Fred Perris) in 1886. There were, however, instances of tension. Some farmers in the Temecula area were reportedly skeptical of the railroad’s precarious route along the flood-prone canyon, advice that proved well-founded when the line washed out. Additionally, the construction crews themselves (many of whom were Chinese) sometimes met prejudice or hostility in local communities, as was common in that era.

On the whole, the coming of the California Southern was a boon to Southern California communities. It broke the isolation of San Diego and San Bernardino, lowered freight rates, and sparked a fare war that made travel more affordable (as detailed in a later section). The railroad also brought jobs and expanded agricultural markets. Conflicts that did occur – aside from corporate battles with Southern Pacific – were relatively minor and often stemmed from disputes over right-of-way or damage to land during construction, which the railroad typically settled. By 1885, most local stakeholders recognized that Santa Fe’s entry via the California Southern meant freedom from the SP monopoly and the start of a more competitive era in transportation.

Completion and Connection at Barstow

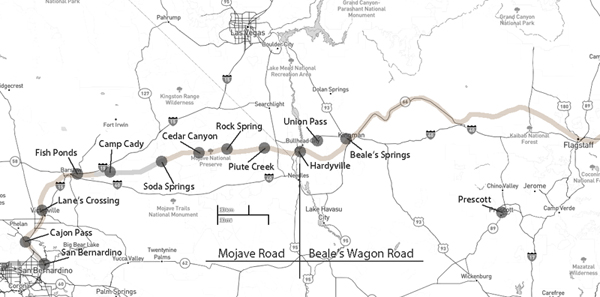

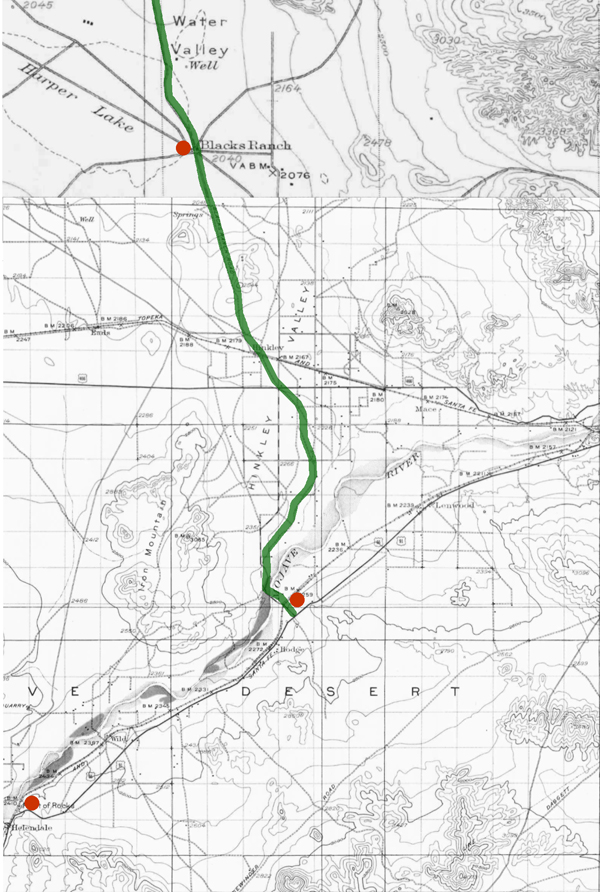

The completion of the California Southern Railroad through Cajon Pass in November 1885 was a pivotal moment in western railroad history. It effectively joined Southern California to the transcontinental rail network, creating a new through route from Chicago (via the Santa Fe and A&P lines) to San Diego and Los Angeles. The meeting point was at the desert town of Barstow – known at the time as Waterman Junction. Barstow was where the California Southern’s rails met the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad (A&P), which had built west from Albuquerque to Needles by 1883. Notably, the tracks between Needles and Barstow had been laid by the Southern Pacific (under an arrangement to block Santa Fe) but were acquired by AT&SF in 1884. Thus, by late 1885, Santa Fe controlled an unbroken line from Kansas City to Barstow.

On November 15, 1885, workers drove the last spike in Cajon Pass, after track gangs from San Bernardino and Barstow met on the grade. Service commenced immediately: on November 16, the first trains to traverse the entire line ran between San Diego and points east. One train originated at Barstow heading toward San Diego, and another left National City (San Diego) bound for the East. These inaugural runs symbolized the end of Southern Pacific’s stranglehold – passengers and freight could now travel over an independent transcontinental route to Southern California. The completion of California Southern also made Barstow a key junction. The town soon developed into a bustling division point, with yards and shops to sort the influx of transcontinental freight descending from the Mojave Desert.

To formalize the connection, the California Southern built a junction with the A&P just outside Barstow. The A&P (which was half-owned by Santa Fe) continued west to Mojave, but Santa Fe shifted its focus to the new link south to San Diego. The entire route operated seamlessly under Santa Fe management, effectively making the California Southern the western leg of Santa Fe’s main line. In railroad publicity, Santa Fe touted its new “Pacific Route” reaching San Diego’s harbor – though Los Angeles would soon eclipse San Diego as the primary terminus (see below). Still, the achievement at Barstow in 1885 cannot be overstated: it completed the second transcontinental railroad into California, providing a competitive alternative to the Central/Southern Pacific’s lines. From this point on, Southern California was served by two transcontinental systems, and Barstow (named in honor of W.B. Strong) became a lasting reminder of Santa Fe’s triumph.

Natural Disasters and Line Modifications

Nature proved to be an ongoing adversary for the California Southern Railroad, even after the line’s completion. The Temecula Canyon segment (between San Diego and San Bernardino) was especially vulnerable. As noted, the Great Flood of 1884 devastated that canyon, shutting down the line for most of that year. The Santa Fe takeover allowed repairs to proceed, and by early 1885, trains were running again. However, the lesson was learned: Temecula Canyon was a risky route. Santa Fe soon invested in alternate lines to avoid this chokepoint (discussed in the next section).

The most fateful natural event came in February 1891, when another series of Pacific storms pounded Southern California. That month saw relentless rainfall and flooding. All railroads in the region were washed out in places, but the Santa Margarita/Temecula Canyon line was hit catastrophically once more. Bridges and tracks that had been rebuilt after 1884 were again torn from their foundations. In some spots, rails were reportedly carried miles downstream, with witnesses claiming they could see railroad ties bobbing in the ocean surf after being swept out of the canyon. This time, the Santa Fe Railroad decided not to pour more money into rebuilding the vulnerable canyon segment. By 1891, an alternate route to San Diego was nearly in place (via Orange County), making the Temecula line somewhat expendable.

After the 1891 floods, Santa Fe permanently abandoned the rail line between Fallbrook (north of Oceanside) and Temecula. No train ever ran through Temecula Canyon again after that disaster. The Santa Fe instead completed its Surf Line down the coast: by 1888, a line was finished from Los Angeles south to Oceanside (connecting with the remaining part of the California Southern into San Diego). Thus, when the 1891 storms destroyed the inland canyon route, Santa Fe shifted all San Diego traffic to the coastal route via Los Angeles. The isolated Temecula canyon grade was left to nature and quickly fell into ruin, save for a few work trains that salvaged usable materials. That segment became one of the West’s earliest mainline abandonments due to natural forces.

Cajon Pass, in contrast, proved more resilient. While subject to occasional flash floods and landslides, the Cajon route did not suffer the kind of complete washouts that Temecula did. The railroad’s engineering (keeping the line above streambeds and providing culverts) paid off. One notable natural incident in Cajon’s later years was a wildfire and subsequent rain in 1923 that caused a major mudslide, but the line was quickly cleared. Overall, the 1891 floods were the turning point that relegated the original San Diego–San Bernardino line to secondary status, while the Cajon Pass route, by virtue of its sturdier construction and strategic importance, remained the primary gateway. The legacy of these natural events is evident in today’s rail map: the coastal Surf Line (Los Angeles–San Diego) became the main passenger route, and Cajon Pass remains a vital freight corridor for the BNSF Railway, whereas Temecula Canyon holds only rusted rails as a historical footnote.

Integration into the Santa Fe System

The California Southern Railroad’s identity as an independent company was relatively short-lived. Once the Santa Fe assumed control in late 1884, the line was gradually folded into Santa Fe’s corporate structure. In 1885, Santa Fe operated it as a subsidiary, using the California Southern name for a few more years. But as Santa Fe rapidly expanded its network in Southern California, it made sense to consolidate its operations. In July 1888, Santa Fe finished its own line into Los Angeles (via Pasadena and the San Gabriel Valley), and by 1888–1889, it had also completed the “Surf Line” along the coast to San Diego. These new lines, along with the California Southern, California Central, and other subsidiaries, were merged in 1889 to form the Southern California Railway Company. The California Southern thus ceased to exist as a separate entity in 1889, becoming part of the Southern California Ry. (a holding company controlled by AT&SF).

This consolidation simplified operations, and soon the Santa Fe system in California was branded simply as the “Santa Fe Route.” In 1893, the parent AT&SF Railway went through a bankruptcy and reorganization (due to over-expansion in the 1880s), emerging in 1895 as the reorganized Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. The Southern California Railway (and all its component former companies, including the California Southern) was fully absorbed into the Santa Fe Railway in the early 1900s once financial stability returned. After 1906, maps no longer labeled the “California Southern”; it was simply the Santa Fe main line.

Under Santa Fe management, the line through Cajon Pass became the backbone of Santa Fe’s Los Angeles Division. While the original intent was to bring trains to San Diego, the Santa Fe soon focused on Los Angeles as the principal Pacific terminus (LA’s larger population and port potential drove this decision). By leasing a short segment from SP, Santa Fe started running trains from San Bernardino into Los Angeles in 1885; by 1887, it built its own line into LA, allowing direct service. Thereafter, most transcontinental trains bypassed the San Diego branch, running from Barstow over Cajon Pass straight to Los Angeles. San Diego was served by a spur line from Orange County (the Surf Line connection completed in 1888). The California Southern’s original route between San Bernardino and San Diego thus became partly a branch line and partly abandoned (after Temecula Canyon’s washout in 1891). Santa Fe did keep the segment from San Bernardino south to Perris and Oceanside in service as the “Fallbrook Line,” but its strategic importance waned.

Meanwhile, Cajon Pass solidified as a critical link in Santa Fe’s transcontinental network. Santa Fe double-tracked Cajon in 1913 (adding tunnels and a parallel route with gentler curvature) to increase capacity. By the mid-20th century, the line was hosting many of Santa Fe’s famous named passenger trains (the Chief, Super Chief, El Capitan, etc., as well as Union Pacific’s Los Angeles Limited under trackage rights). In the Santa Fe corporate lineage, the California Southern was the progenitor of all Santa Fe lines in Southern California. That heritage lives on: after the AT&SF merged into BNSF Railway in 1995, the Cajon Pass route remains one of BNSF’s busiest main lines, shared with the Union Pacific by agreement. The once-independent California Southern is thus fully integrated – it became the rail highway by which modern container trains and Amtrak passenger service reach Los Angeles, a far cry from its humble, struggling beginnings in the 1880s.

Regional Impact and Legacy

The construction of the California Southern Railroad through Cajon Pass had profound effects on Southern California’s development. Most immediately, it broke the Southern Pacific’s monopoly on transcontinental rail service to the region. With Santa Fe as a competitor, shipping costs and passenger fares plummeted. By the late 1880s, tickets from the Midwest to California dropped from over $100 to as low as $25. A famous rate war in 1886–1887 even saw cross-country fares temporarily fall to nearly zero, as the railroads competed for settlers. The result was a population and economic boom in Southern California, notably the great “Boom of the Eighties.” Towns along the Santa Fe lines prospered. For example, San Bernardino grew as a rail hub with a grand Santa Fe depot (completed 1886), and new agricultural communities bloomed in areas now reachable by rail. Santa Fe’s presence enabled citrus growers in San Bernardino and Riverside counties to ship oranges to eastern markets in refrigerated railcars, sparking the Citrus Belt boom. Likewise, farmers and ranchers benefited from lower freight rates for importing equipment and exporting produce.

The linkage through Cajon Pass also elevated Los Angeles and San Diego as seaports. While San Diego’s direct line suffered from the Temecula washouts, the city still gained a reliable connection by 1888 via the Santa Fe’s coastal line. The famous Hotel Del Coronado (opened in 1888 in San Diego) was built to accommodate wealthy eastern tourists arriving on Santa Fe’s line. Los Angeles, connected in 1887, saw an explosion of growth; Santa Fe’s entry sparked a real estate boom and gave Los Angeles a second transcontinental outlet in addition to the SP line from the north. By securing its own route into Los Angeles (completed just after Cajon in 1887), Santa Fe ensured the region would have long-term competitive rail service.

Cajon Pass’s railroad itself became an enduring asset. Despite the challenges posed by its 3.4% grade, it enabled direct freight routes from the port of Los Angeles to the rest of the country, cementing LA’s status as a significant trade center. Over the decades, Santa Fe upgraded the route (reducing the summit elevation slightly and easing curves in the 1960s). In modern times, BNSF and Union Pacific each operate multiple main tracks through the Cajon Pass to handle the enormous flow of cargo containers from the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. The line is so busy and scenic that Cajon Pass has become a famous railfanning location, with photographs of long freight trains snaking through its dramatic mountain backdrop appearing in countless books and magazines.

Finally, the legacy of the California Southern Railroad is seen in the place names and cultural memory it left behind. The city of Perris and the town of Barstow commemorate figures who built the line. The phrase “Second Transcontinental Railroad” is often applied to the Santa Fe’s route via Cajon Pass, acknowledging that the 1885 completion was the first true competitor to the original 1869 transcontinental line. Today’s Interstate 15 roughly follows the Cajon Pass rail corridor, a testament to how railroad pioneers found a practical route through the mountains. In sum, what began as a risky venture by the California Southern in 1880 blossomed into a key component of a national railway system, transforming Southern California’s economy and transportation landscape. The trains that labor up the steep grades of Cajon Pass today are living proof of the region’s 19th-century railroad heritage – a legacy of bold surveying, arduous construction, and the triumph over geographic odds.

Santa Fe locomotives climb the 2.2% grade on a newer alignment near Cajon Summit in 1964. The Cajon Pass rail corridor – first opened in 1885 – remains a crucial and busy route, now part of BNSF Railway’s transcontinental line.

Sources:

- Serpico, Philip C. Santa Fé Route to the Pacific (Omni Publications, 1988), pp. 18–24 – via Wikipedia.

- Burns, Adam. “Cajon Pass (Railroad Grade): History & Map.” (updated Aug. 24, 2024)

- Rails West. “Second Transcontinental Line to California – ATSF Brings Competition.” RlsWest.com (Richard Boehle).

- Dodge, Richard V. “History of the California Southern Railway (Fallbrook Line).” Mojave Desert Archives (1957).

- Santa Margarita Ecological Reserve (San Diego State Univ.). “The Historic California Southern Railroad.” (n.d.)

- Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection. “Santa Fe R.R. in Cajon Pass” (Photograph, ca. 1885, engine #40 at Cajon Summit).

- San Diego History Center. “The California Southern Railroad and the Growth of San Diego” (Article, n.d.)

- Perris City Historical Archives. “Frederick T. Perris” (Biography)