The chuckwalla, scientifically known as Sauromalus ater, is a fascinating reptile that calls the arid regions of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico its home. With its distinctive appearance and intriguing behaviors, the chuckwalla has captivated the interest of scientists and nature enthusiasts alike.

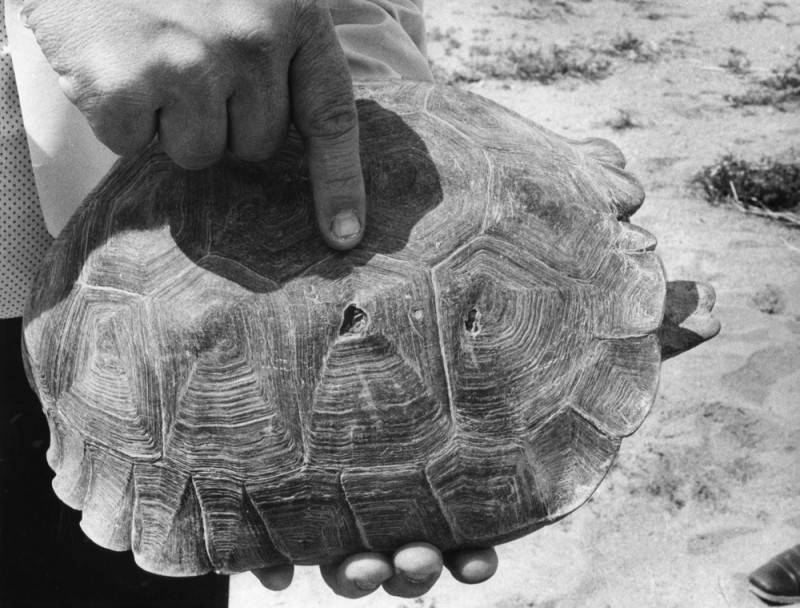

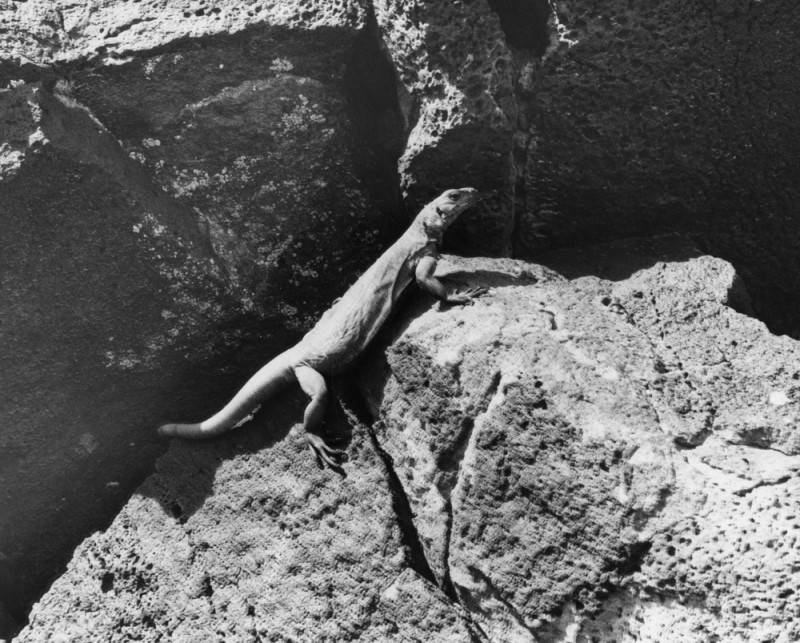

One of the most striking features of the chuckwalla is its robust and stocky build. These lizards can grow up to 15 inches in length and have a heavyset body covered in rough, granular scales. Their coloration varies, but they are often seen in shades of gray, brown, or black, which helps them blend seamlessly with their rocky desert surroundings.

Chuckwallas are primarily herbivorous, feasting on a diet consisting mainly of leaves, flowers, fruits, and the occasional insect. Their specialized digestive system allows them to efficiently process plant materials, making them well-suited to their desert habitat where vegetation can be scarce.

In terms of behavior, the chuckwalla is known for its ability to regulate body temperature through basking in the sun. They are often seen perched on rocks, soaking up the desert heat. This behavior is crucial for their survival in the extreme desert environment, as it enables them to reach their optimal body temperature for digestion and overall functioning.

Another interesting characteristic of the chuckwalla is its ability to inflate itself when threatened. When cornered or feeling endangered, it wedges itself into rock crevices and puffs up its body, making it difficult for predators to extract them. This defense mechanism and their excellent climbing skills help ensure their survival in the harsh desert landscape.

Despite their resilient nature, chuckwallas face numerous challenges in their habitat. Habitat loss due to human activities, such as urbanization and agriculture, poses a significant threat to their population. Climate change and increased predation from invasive species further exacerbate their vulnerability.

Conservation efforts are crucial to safeguard the chuckwalla population and its habitat. Protecting their natural habitat, promoting awareness, and implementing measures to mitigate human impact are essential steps in preserving these enigmatic desert lizards for future generations to appreciate.

In conclusion, the chuckwalla is a remarkable reptile that has adapted to thrive in the harsh desert environment. Its unique physical features, specialized diet, and intriguing behaviors make it a subject of interest for researchers and nature enthusiasts alike. By understanding and protecting these mysterious creatures, we can ensure their survival and contribute to the preservation of the delicate desert ecosystems they call home.