A Braided Tale

The story of Willie Boy is one of the most haunting and complex episodes in the history of the California desert. It begins in the early autumn of 1909, when a young Chemehuevi-Paiute man named Willie Boy falls deeply in love with Carlota, the daughter of a respected tribal elder. Their romance, set in the desert landscapes around Banning and Twentynine Palms, was as ill-fated as any tragic ballad of the Old West, and it ended in bloodshed, loss, and a manhunt that became part of American legend.

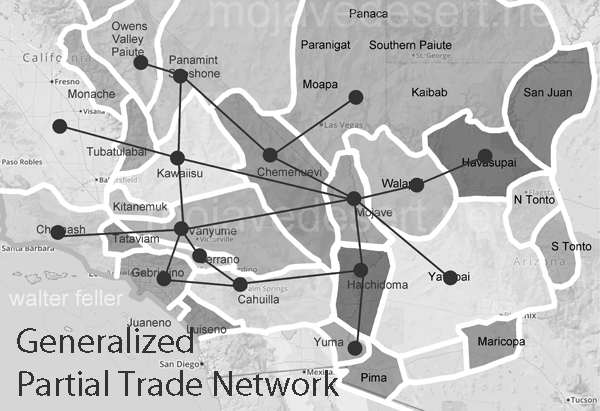

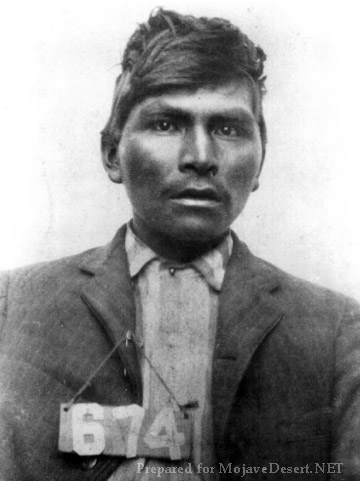

Willie Boy was about twenty-eight years old, a Chemehuevi from the Southern Paiute people, raised near the Colorado River but often working for white ranchers in the San Gorgonio Pass area. He was a quiet man, by most accounts, known for his skill as a runner and his ability as a capable worker. Carlota was sixteen, the daughter of William and Maria Mike, who lived with their people at the Oasis of Mara, now part of Joshua Tree National Park. Their families knew each other, but Chemehuevi tradition forbade marriage between cousins, which made the match impossible in the eyes of her father.

When Willie Boy and Carlota ran off together, they defied both cultural law and parental authority. They were brought back once, but they met again later that year when the Mike family traveled to Banning for the fall fruit harvest. The reunion of the two lovers set the final tragedy in motion. One evening in late September 1909, Willie Boy went to the Mike family’s camp near the Gilman Ranch to ask for Carlota’s hand. Her father, a strong-willed and traditional man, refused him flatly. Some say the older man reached for a gun, others that Willie Boy had brought one and lost his nerve. There was a struggle, a shot, and when the dust settled, William Mike lay dead. Whether the shooting was deliberate or accidental has never been settled.

Knowing that the white authorities would come for him, Willie Boy fled into the desert with Carlota. They rode and walked across the dry country east of Banning, following faint trails and water holes that only local people knew. When Maria Mike discovered her husband’s body at dawn, she reported the killing to the sheriff. Within hours, a posse had formed, led by Riverside County Sheriff Frank Wilson and his deputy Ben de Crevecoeur. With them were a handful of local ranchers and two Native trackers, John Hyde and Segundo Chino.

The chase that followed quickly became a national story. Newspapers painted Willie Boy as a savage outlaw, “a drunken Piute renegade” who had killed in a jealous rage and carried off a helpless girl. The language was raw, racist, and designed to sell papers. Reporters wrote that the “bloodthirsty Indian” might even threaten President Taft, who happened to be visiting Riverside that week. This hysteria turned a local tragedy into a full-blown legend.

Meanwhile, Willie Boy and Carlota pressed deeper into the Mojave. They moved mostly at night, hiding by day in the arroyos and canyons. Willie Boy’s endurance was remarkable; he could travel fifty miles across rough ground in a day. But they were running low on food and water, and the posse was relentless.

At some point during the pursuit, Carlota was killed. Her body was found later, shot through the back. Early newspaper reports said Willie Boy had murdered her so she would not slow him down. That version fit the outlaw story perfectly, but later investigations suggest otherwise. The coroner’s report showed she was shot from long range, likely by a posse member who mistook her for Willie Boy. She was wearing his coat at the time. Decades later, oral histories from the Chemehuevi confirmed that this is what their elders always believed: that the white men killed Carlota by mistake, then blamed her lover to save face.

After Carlota’s death, the posse pressed on. The final confrontation came at Ruby Mountain, near what is now Landers. Willie Boy took a defensive position among the rocks. As the posse approached, he opened fire, deliberately aiming for their horses rather than their riders. One deputy, Charlie Reche, was wounded in the arm. The standoff lasted all day until the lawmen pulled back to tend to the injured. At sunset, they heard a single gunshot from the mountain. They assumed Willie Boy had turned the gun on himself. When they returned a few days later, they found a badly decomposed body lying near a rifle and declared the manhunt over. They burned the remains on the spot rather than carrying them out of the desert.

That cremation left no evidence. No one could later prove that the body was Willie Boy’s, and none of the posse’s surviving photographs show a face that can be identified. This gap opened the door to one of the enduring mysteries of the story. Among the Chemehuevi, Paiute, and Cahuilla people, the belief persisted that Willie Boy escaped. They said he traveled north through the desert and eventually settled with relatives near Pahrump, Nevada, living quietly until tuberculosis took him years later. Segundo Chino, one of the trackers on the posse who later married Maria Mike, is said to have admitted that the posse never actually caught Willie Boy.

The events deeply shook the Chemehuevi community. They left their traditional home at the Oasis of Mara, afraid that William Mike’s restless spirit might bring misfortune. For many years, they refused to speak of the tragedy. In that silence, white writers filled the void. The newspapers portrayed Willie Boy as a villain and the manhunt as a piece of frontier nostalgia.

Half a century later, journalist Harry Lawton rediscovered the tale. Working from old newspaper clippings and interviews with surviving posse members, he published Willie Boy: A Desert Manhunt in 1960. His book treated the story as both history and myth, but it still leaned toward the posse’s version. The novel won awards and inspired the 1969 film Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here, directed by Abraham Polonsky and starring Robert Blake and Robert Redford. The film gave the story a tragic, modern edge and questioned some of the old assumptions, but it also cemented certain inaccuracies in popular memory.

In the 1990s, historians James Sandos and Larry Burgess revisited the story in The Hunt for Willie Boy: Indian-Hating and Popular Culture. They demonstrated how racism and sensationalism influenced the original reports and concluded that many of the most colorful details were fabricated. They agreed that Carlota was almost certainly killed by the posse, not by Willie Boy, but they accepted that he probably died on Ruby Mountain.

A generation later, Native historian Clifford Trafzer went further. Drawing on oral histories from Chemehuevi and Cahuilla elders, he argued that the man the posse burned was not Willie Boy at all. In the stories told by his people, Willie Boy survived the chase, lived for years among the Paiute in Nevada, and died quietly of illness. Trafzer’s work reframed the legend as a Native tragedy rather than a Western adventure.

For the Chemehuevi and other desert people, the story of Willie Boy and Carlota is more than a love story gone wrong. It represents the collision of two worlds: traditional tribal law and the laws of the new American order. It marks the loss of a way of life and the pain of a community forced into silence.

Today, the tale continues to echo across the desert. Artists and filmmakers have attempted to retell the story from the Native perspective. In 2016, Cahuilla artist Lewis de Soto created an installation in Twentynine Palms called Carlota, giving voice to the young woman whose story had long been overshadowed. In 2022, Jason Momoa produced The Last Manhunt, a film made in collaboration with the Chemehuevi that depicts the event as the tribe remembers it.

Whether Willie Boy died on Ruby Mountain or escaped into the Nevada desert may never be known. What is certain is that his story reveals how quickly truth can be twisted by fear and prejudice, and how long it can take for those who were silenced to be heard again.

The Willie Boy saga began as a local tragedy, became a legend through the press, and has endured as a window into the uneasy meeting of cultures in the desert. It reminds us that history is not fixed in stone, but lives in the voices of those who tell it, and that sometimes the best we can do is listen to all of them.