Seventy-five years in California; a history of events and life in California

CHAPTER XV Indian Insurrections and Treachery

OCCASIONALLY the Indians who had been at the Missions, and had become well informed in regard to the surrounding neighborhood and the different ranches in the vicinity, would desert the Missions, retreat to their old haunts and join the uncivilized Indians. At times they would come back with some of the wild Indians to the farms, for the purpose of raiding upon them, and capturing the domesticated horses. They would come quietly in the night, and carry off one or two caponeras of horses, sometimes as many as five or six, and drive them back to the Indian country for their own use.

In the morning a ranchero would discover that he was without horses for the use of the ranch. He would then borrow some horses from his neighbor, and ten or twelve men would collect together and go in pursuit of the raiders. They were nearly always successful in overtaking the thieves and recovering their horses, though oftentimes not without a fierce fight with the Indians, who were armed with bows and arrows, and the Californians with horse carbines. At these combats the Indians frequently lost some of their number, and often as many as eight or ten were killed. The Californians were sometimes wounded and occasionally killed. Once in a while, but very seldom, the Indians were successful in eluding pursuit, and got safely away with the horses, beyond recovery.

In the early part of ’39, nearly all the saddle horses belonging to Captain Ygnacio Martinez, at the rancho Pinole, were thus carried off by the Indians, and his son Don José Martinez, (whose niece I afterward married), with eight or ten of his neighbors, went in pursuit of them, and though they succeeded in recovering the animals, they lost one of their number, Felipe Briones, who was killed by an arrow. The fight on that occasion was exceedingly severe, and the Indians became so incensed, and their numbers increased so much, that the little party deemed it too hazardous to continue the fight, and retreated, taking with them the recovered horses, but were compelled to leave the body of Briones on the field. Two days afterward the party went back and recovered it, but found it terribly mutilated. Some eight or ten of the Indians were killed by the Californians in that fight.

Juan Prado Mesa was the comandante of the San Francisco Presidio, and frequently left his post to go in campaigns against the Indians with part of his command. He was always considered a successful Indian fighter. He was a brave and good man. On one occasion he was wounded with an arrow, which ultimately carried him to his grave. He was blessed with a large family. I became very well acquainted with him, and he frequently furnished me with fine saddle horses and a vaquero to make my business circuit around the bay. He was under the immediate command of General Vallejo, with whom he was intimate, and sometimes he confided to me secret movements of the government. The Californians were early risers. The ranchero would frequently receive a cup of coffee or chocolate in bed, from the hands of a servant, and on getting up immediately order one of the vaqueros to bring him a certain horse which he indicated, every horse in a caponera having a name, which was generally bestowed on account of some peculiarity of the animal. He then mounted and rode off about the rancho, attended by a vaquero, coming back to breakfast between eight and nine o’clock.

This breakfast was a solid meal, consisting of carne asada (meat broiled on a spit), beefsteak with rich gravy or with onions, eggs, beans, tortillas, sometimes bread and coffee, the latter often made of peas. After breakfast, the ranchero would call for his horse again, usually selecting a different one, not because the first was fatigued, but as a matter of fancy or pride, and ride off again around the farm or to visit the neighbors. He was gone till twelve or one o’clock, when he returned for dinner, which was similar to breakfast, after which he again departed, returning about dusk in the evening for supper, this being mainly a repetition of the two former meals. Although there was so little variety in their food from one day to another, everything was cooked so well and so neatly and made so inviting, the matron of the house giving her personal attention to everything, that the meals were always relished.

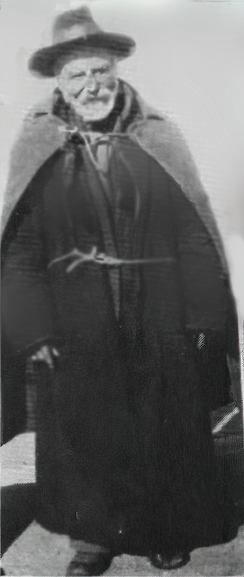

When the rancheros thus rode about, during the leisure season, which was between the marking time and the matanza or killing time, and from the end of the matanza to the spring time again, the more wealthy of them were generally dressed in a good deal of style, with short breeches extending to the knee, ornamented with gold or silver lace at the bottom, with botas (leggings) below, made of fine soft deerskin, well tanned and finished, richly colored, and stamped with beautiful devices (these articles having been imported from Mexico, where they were manufactured), and tied at the knee with a silk cord, two or three times wound around the leg, with heavy gold or silver tassels hanging below the knee. They wore long vests, with filagree buttons of gold or silver, while those of more ordinary means had them of brass. They wore no long coats, but a kind of jacket of good length, most generally of dark blue cloth, also adorned with filagree buttons. Over that was the long serape or poncho, made in Mexico and imported from there, costing from $20 to $100, according to the quality of the cloth and the richness of the ornamentation. The serape and the poncho were made in the same way as to size and cut of the garments, but the former was of a coarser texture than the latter, and of a variety of colors and patterns, while the poncho was of dark blue or black cloth, of finer quality, generally broadcloth. The serape was always plain, while the poncho was heavily trimmed with gold or silver fringe around the edges, and a little below the collars around the shoulders.

They wore hats imported from Mexico and Peru, generally stiff; the finer quality of softer material — vicuña, a kind of beaver skin obtained in those countries. Their saddles were silver-mounted, embroidered with silver or gold, the bridle heavily mounted with silver, and the reins made of the most select hair of the horse’s mane, and at a distance of every foot or so there was a link of silver connecting the different parts together. The tree of the saddle was similar to that now in use by the Spaniards and covered with the mochila, which was of leather. It extended beyond the saddle to the shoulder of the horse in front and back to the flank, and downwards on either side, halfway between the rider’s knee and foot. This was plainly made, sometimes stamped with ornamental figures on the side and sometimes without stamping. Over this was the coraza, a leather covering of finer texture, a little larger and extending beyond the mochila all around, so as to cover it completely. It was elaborately stamped with handsome ornamental devices.

Behind the saddle, and attached thereto, was the anqueta, of leather, of half-moon shape, covering the top of the hindquarters of the horse, but not reaching to the tail; which was also elaborately stamped with figures and lined with sheep skin, the wool side next to the horse. This was an ornament, and also a convenience in case the rider chose to take a person behind him on the horse.

Frequently some gallant young man would take a lady on the horse with him, putting her in the saddle in front and himself riding on the anqueta behind.

The stirrups were cut out of a solid block of wood, about two and a half inches in thickness. They were very large and heavy. The strap was passed through a little hole near the top. The tapadera was made of two circular pieces of very stout leather, about twelve to fifteen inches in diameter, the outer one a little smaller than the inner one, fastened together with strips of deer skin called gamuza, the saddle strap passing through two holes near the top to attach it to the stirrup; so that when the foot was placed in the stirrup the tapadera was in front, concealed it, and protected the foot of the rider from the brush and brambles in going through the woods.

This was the saddle for everyday use of the rancheros and vaqueros, that of the former being somewhat nicer and better finished. The reins for everyday use were made of deer or calfskin or other soft leather, cut in thin strips and nicely braided and twisted together, and at the end of the reins was attached an extra piece of the same with a ring, which was used as a whip. Their spurs were inlaid with gold and silver, and the straps of the spurs worked with silver and gold thread.

When thus mounted and fully equipped, these men presented a magnificent appearance, especially on the feast days of the Saints, which were celebrated at the Missions. Then they were arrayed in their finest and most costly habiliments, and their horses in their gayest and most expensive trappings. They were usually large, well-developed men, and presented an imposing aspect. The outfit of a ranchero and his horse, thus equipped, I have known to cost several thousand dollars. The gentleman who carried a lady in this way, before him on a horse, was considered as occupying a post of honor, and it was customary when a bride was to be married in a church, which was usual in those days, for a relative to take her before him in this fashion on his horse to the church where the ceremony was to be performed. This service, which involved the greatest responsibility and trust on the part of the gentleman, was discharged by him in the most gallant and polite manner possible.

On the occasion of my marriage, in 1847, the bride was taken in this way to the church by her uncle, Don José Martinez. On these occasions the horse was adorned in the most sumptuous manner, the anqueta and coraza being beautifully worked with ornamental devices in gold and silver thread. The bride rode on her own saddle, sometimes by herself, which was made like the gentleman’s but a little smaller, and without stirrups, in place of which a piece of silk—red, blue, or green—perhaps a yard wide and two or three yards long, joined at the two ends, was gracefully hung over the saddle, puffed like a bunch of flowers at the fastening, and hung down at one side of the horse in a loop, in which the lady lightly rested her foot.

The ladies were domestic and exceedingly industrious, although the wealthier class had plenty of Indian servants. They were skillful with their needles, making garments for their families, which were generally numerous. The women were proficient in sewing. They also did a good deal of nicer needlework of fancy kinds—embroidery, etc.—in which they excelled, all for family use. Their domestic occupations took up most of their time.

Both men and women preserved their hair in all its fullness and color, and it was rare to see a gray-headed person. A man fifty years of age, even, had not a single gray hair in his head or beard, and I don’t remember ever seeing, either among the vaqueros or the rancheros or among the women, a single bald-headed person. I frequently asked them what was the cause of this remarkably good preservation of their hair, and they would shrug their shoulders, and say they supposed it was on account of their quiet way of living and freedom from worry and anxiety.

The native Californians were about the happiest and most contented people I ever saw, as also were the early foreigners who settled among them and intermarried with them, adopted their habits and customs, and became, as it were, a part of themselves. Among the Californians, there was more or

less caste, and the wealthier families were somewhat aristocratic and did not associate freely with the humbler classes; in towns, the wealthy families were decidedly proud and select, the wives and daughters especially. These people were naturally, whether rich or poor, of a proud nature, and though always exceedingly polite, courteous, and friendly, they were possessed of a native dignity, an inborn aristocracy, which was apparent in their bearing, walk, and general demeanor. They were descended from the best families of Spain and never seemed to forget their origin, even if their outward surroundings did not correspond to their inward feeling. Of course, among the wealthier classes, this pride was more manifest than among the poorer.

In my long intercourse with these people, extending over many years, I never knew of an instance of incivility of any kind. They were always ready to reply to a question, and answered in the politest manner, even the humblest of them; and in passing along the road, the poorest vaquero would salute you politely. If you wanted any little favor of him, like delivering a message to another rancho, or anything of that sort, he was ready to oblige and did it with an air of courtesy and grace and freedom of manner that were very pleasing. They showed everywhere and always this spirit of accommodation, both men and women. The latter, though reserved and dignified, always answered politely and sweetly, and generally bestowed upon you a smile, which, coming from a handsome face, was charming in the extreme. This kindness of manner was no affectation, but genuine goodness, and commanded one’s admiration and respect.

I was astonished at the endurance of the California women in holding out, night after night, in dancing, of which they never seemed to weary, but kept on with an appearance of freshness and elasticity that was as charming as surprising. Their actions, movements, and bearing were as full of life and animation after several nights of dancing as at the beginning, while the men, on the other hand, became wearied, showing that their powers of endurance were not equal to those of the ladies. I have frequently heard the latter ridiculing the gentlemen for not holding out unfatigued to the end of a festival of this kind.

The rancheros and their household generally retired early, about eight o’clock, unless a valecito casaro (little home party) was on hand when this lasted till twelve or one. They were fond of these gatherings, and almost every family had some musician of its own, music and dancing were indulged in, and a very pleasant time was enjoyed. I have attended many of them and always was agreeably entertained. These parties were usually impromptu, without formality, and were often held for the entertainment of a guest who might be stopping at the house. The balls or larger parties were of more importance and usually occurred in the towns. On the occasion of the marriage of a son or daughter of a ranchero they took place on the rancho, the marriage being celebrated amid great festivities, lasting several days.

Fandango was a term for a dance or entertainment among the lower classes, where neighbors and others were invited in, and engaged themselves without any great degree of formality. The entertainments of the wealthy and aristocratic class were more exclusive in character; invitations were more carefully given, more formality observed, and of course, more elegance and refinement prevailed. An entertainment of this character was known as a baile.

In November 1838, I was a guest at the wedding party given at the marriage of Don José Martinez to the daughter of Don Ygnacio Peralta, which lasted about a week, dancing being kept up all night with a company of at least one hundred men and women from the adjoining ranchos, about three hours after daylight being given to sleep, after which picnics in the woods were held during the forenoon, and the afternoon was devoted to bullfighting. This program was continued for a week when l myself had become so exhausted for want of regular sleep that I was glad to escape.

The bride and bridegroom were not given any seclusion until the third night.

On this occasion Doña Rafaela Martinez, wife of Dr. Tennent, and sister of the bridegroom, a young woman full of life and vivacity, very attractive and graceful in manner, seized upon me and led me on to the floor with the waltzers. I was ignorant of waltzing up to that moment. She began moving around the room with me in the waltz, and in some unaccountable manner, perhaps owing to her magnetism, I soon found myself going through the figure with ease. After that, I had no difficulty in keeping my place with the other waltzers and was reckoned as one of them. I waltzed with my fascinating partner for a good portion of the night.

During this festivity, Don José Martinez, who was a wonderful horseman, performed some feats which astonished me. For instance, while riding at the greatest speed, he leaned over his saddle to one side, as he swept along, and picked up from the ground a small coin, which had been put there to try his skill, and then went on without slackening his speed.

Some years after that I was visiting him, and while we were out taking a ride over his rancho, we came to an exceedingly steep hill, almost perpendicular; at the top was a bull quietly feeding. He looked up and said, “Do you see that bull?” “Yes,” said I. “Now,” said he, “we will have some fun. I am going up there to drive him down and lasso him on the way.” It seemed impossible owing to the steepness of the declivity. Nevertheless, he did it, rode up to the top, started the bull down at full speed, and actually lassoed the animal on the way, threw him down, and the bull at once commenced rolling down the steep side of the hill, over and over, until he reached the bottom, José following on his horse and slackening up the riata as he went along. He was a graceful rider.

After many years of happiness with his excellent wife, during which they were blessed with six or eight children, Don José Martinez became a widower. A few years after this he married an English lady, a sister of Dr. Samuel J. Tennent, who was then living at Pinole ranch, and who married a sister of Don José Martinez. Dr. Tennent lived on a portion of the ranch inherited by his wife. The marriage of Don José to a lady outside of his own countrywoman was rather an unusual occurrence among the Californians. The marriage proved a happy one, and half a dozen children resulted therefrom. This lady is now living in San Francisco (1889).

Don José Martinez had the largest kind of heart, and if anyone called at his house who was in need of a horse, he was never refused, and the people of the surrounding country were constantly in receipt of favors at his hands. If one wanted a bullock and had no means to pay for it, he would send out a vaquero to lasso one and bring it in and tie it to a cabestro (a steer broken for that purpose), so that the man could take it home, and told him he might pay for it when convenient, or if not convenient, it was no matter. So with a horse which he might furnish, it didn’t matter whether the animal was returned or not. This generosity was continual 70 and seemed to have no limit. At his death, which occurred in 1864, his funeral was attended by a vast concourse of people from all the surrounding country, who came in wagons, buggies, and carriages to the number of several hundred vehicles, such was the high appreciation in which he was held by the community.

I never saw such respect paid to the memory of any other person. If true generosity and genuine philanthropy entitle a man to a place in the kingdom of Heaven, I am sure that Don José Martinez is received there as one of the chief guests.

Seventy-five years in California; a history of events and life in California http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.025