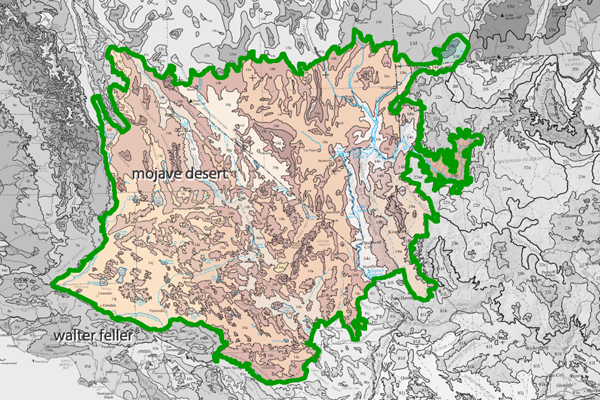

/mojave-preserve/

The Mojave National Preserve, encompassing over 1.6 million acres, offers diverse landscapes, wildlife, and recreational activities. Located in southeastern California, the preserve is a haven for outdoor enthusiasts and nature lovers. Here’s an expanded look at what makes the Mojave National Preserve a popular destination:

Key Features and Attractions

- Kelso Dunes:

- Dune Field: Covering over 45 square miles, the Kelso Dunes are some of the tallest dunes in North America, with the highest peak rising about 650 feet.

- Hiking and Exploration: Visitors can hike to the top of the dunes for panoramic views and experience the phenomenon of “singing sands,” a booming sound produced by the movement of the sand.

- Sunset Views: The dunes are stunning at sunset when the shifting light creates dramatic shadows and colors.

- Hole-in-the-Wall:

- Geological Features: This area is named for its unique rock formations created by volcanic activity and erosion. The walls are filled with holes and cavities, giving the area its distinctive appearance.

- Rings Loop Trail: A popular 1.5-mile loop trail that features metal rings bolted into the rock to help hikers navigate steep sections of the trail. The trail offers a close-up view of the fascinating rock formations.

- Visitor Center: The Hole-in-the-Wall Information Center provides exhibits on the area’s geology, wildlife, and cultural history.

- Cinder Cone Lava Beds:

- Volcanic Landscape: This area features ancient volcanic cones, lava flows, and craters, offering a rugged and dramatic landscape.

- Hiking Trails: Trails wind through the lava beds, providing opportunities to explore the unique terrain and view the surrounding desert.

- Mitchell Caverns:

- Limestone Caves: Located in the Providence Mountains State Recreation Area, these caverns are filled with stalactites, stalagmites, and other fascinating formations.

- Guided Tours: The only way to explore the caverns is through guided tours offered by California State Parks, which provide insights into the caves’ geological history and natural features.

- Mojave Road:

- Historic Route: The Mojave Road is a historic 140-mile off-road trail that follows a route used by Native Americans, early explorers, and settlers. It provides a challenging and adventurous way to experience the preserve.

- Landmarks: Along the route, travelers can see historic sites, old military forts, and natural landmarks. The route requires a high-clearance 4WD vehicle and careful planning.

Wildlife and Plant Life

- Desert Flora: The preserve has various desert plants, including Joshua trees, creosote bushes, cacti, and wildflowers. Springtime can bring vibrant blooms, adding color to the landscape.

- Wildlife: The preserve’s diverse habitats support a wide range of wildlife, including bighorn sheep, coyotes, desert tortoises, and numerous bird species. The varying elevations and environments within the preserve create unique ecosystems.

Recreational Activities

- Hiking:

- Diverse Trails: The preserve offers a range of hiking trails, from short nature walks to strenuous backcountry routes. Trails provide opportunities to explore the varied landscapes and observe the native flora and fauna.

- Backpacking: For those seeking a more immersive experience, the preserve offers backcountry camping and backpacking opportunities. Permits are required for overnight stays.

- Camping:

- Developed Campgrounds: The preserve has several developed campgrounds, including Hole-in-the-Wall and Mid Hills, which offer amenities such as picnic tables, fire rings, and restrooms.

- Dispersed Camping: For a more primitive experience, visitors can camp in designated areas throughout the preserve. Dispersed camping allows for solitude and a closer connection with nature.

- Stargazing:

- Dark Skies: The remote location of the preserve provides excellent conditions for stargazing. The lack of light pollution allows for clear views of the night sky, making it a perfect spot for observing stars, planets, and meteor showers.

- Bird Watching:

- Diverse Bird Species: The varied habitats within the preserve attract a wide range of bird species, making it a popular destination for bird watchers. Seasonal migrations and diverse environments provide opportunities to see both resident and migratory birds.

- Off-Roading:

- Designated Routes: The preserve has numerous designated off-road vehicle routes, offering adventurous ways to explore the rugged terrain. It’s important to stay on designated routes to protect the environment and adhere to regulations.

Historical and Cultural Sites

- Kelso Depot: A restored 1924 Union Pacific train depot now serving as the preserve’s visitor center. The depot features exhibits on the history of the railroad, mining, and desert communities.

- Rock Springs Land and Cattle Company: Historical ranch buildings and corrals that provide a glimpse into the ranching history of the area.

Conservation and Preservation

- Protected Area: The Mojave National Preserve is managed by the National Park Service, protecting its unique landscapes, wildlife, and cultural resources.

- Leave No Trace: Visitors are encouraged to practice Leave No Trace principles, minimizing their impact on the environment and helping to preserve the preserve’s natural beauty and integrity.

Visitor Information

- Accessibility: The preserve is accessible via Interstate 15 and Interstate 40, with several entry points and visitor centers providing information and resources.

- Seasonal Considerations: The best times to visit are spring and fall when temperatures are moderate. Summer temperatures can be extreme, and winter can bring cold nights and occasional snow at higher elevations.

The Mojave National Preserve offers a diverse and captivating landscape with countless opportunities for exploration and adventure. Whether hiking through rugged canyons, climbing towering dunes, or simply soaking in the vast desert vistas, the preserve provides a memorable and enriching experience for all who visit.