https://mojavedesert.net/ecology/

California is home to high and low deserts, characterized by distinct features, climates, and elevations. The primary differences between California’s high and low deserts include elevation, temperature, and vegetation.

- Elevation:

- High Desert: The high desert refers to areas at higher elevations, typically between 2,000 and 4,000 feet above sea level. Examples of high desert regions in California include the Mojave Desert. Cities like Lancaster and Palmdale are located in the high desert region.

- Low Desert: The low desert, on the other hand, is found at lower elevations, often below 2,000 feet. The Colorado Desert, part of the larger Sonoran Desert, is an example of a low desert in California. Cities like Palm Springs and Indio are located in the low desert region.

- Temperature:

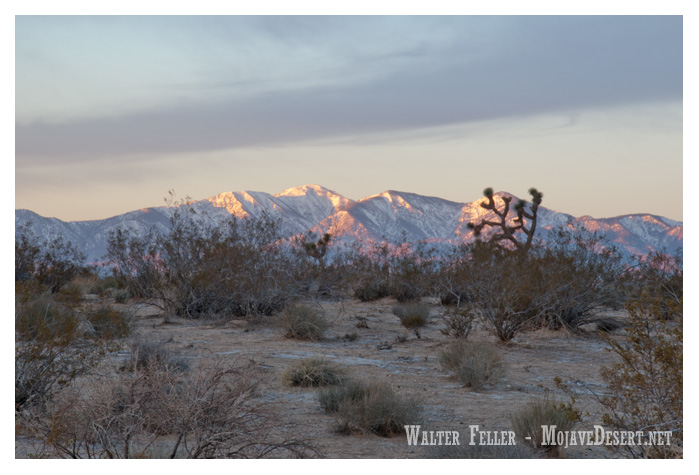

- High Desert: High deserts generally experience greater temperature fluctuations between day and night. Summers can be hot, with daytime temperatures exceeding 100°F (37.8°C), while winters can be cool, with nighttime temperatures dropping significantly.

- Low Desert: Low deserts tend to have higher average temperatures, especially during the summer. Daytime temperatures in the low desert areas can often surpass 100°F (37.8°C), and the winters are milder compared to the high deserts.

- Vegetation:

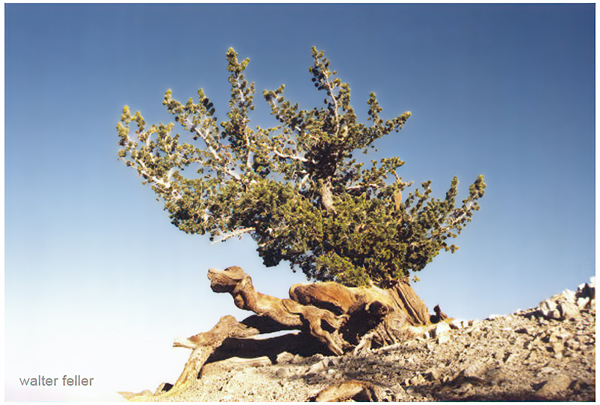

- High Desert: Vegetation in the high desert is adapted to the arid conditions and includes hardy shrubs, grasses, and some cold-resistant plants. Joshua trees are a characteristic plant of the Mojave Desert.

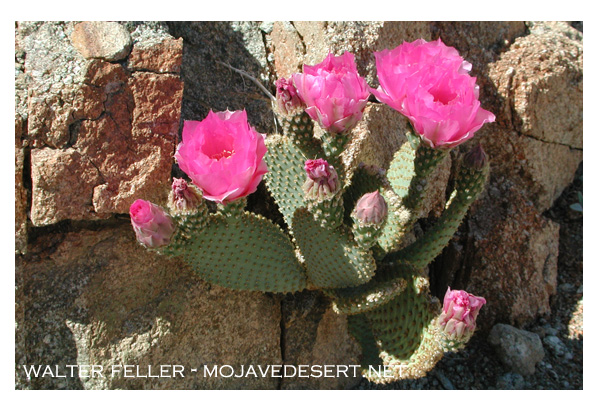

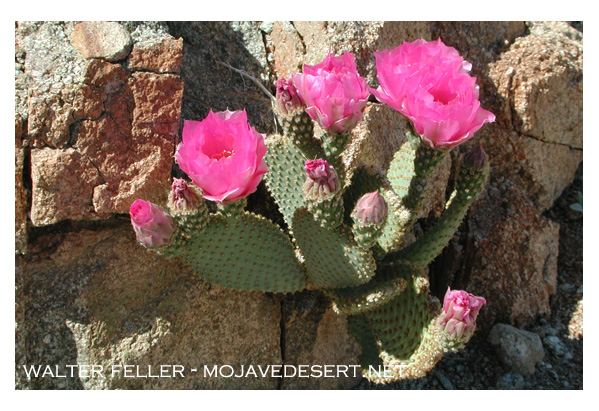

- Low Desert: The low desert is known for its unique plant life, including various species of cacti and succulents. The iconic saguaro cactus is commonly found in the lower elevations of the Sonoran Desert.

- Geography:

- High Desert: The high desert often features rocky terrain and vast expanses of open land and is characterized by a mix of mountains, plateaus, and valleys.

- Low Desert: The low desert may have more sandy and flat terrain, including areas with salt flats. Rugged mountains may also punctuate the landscape.

It’s important to note that these are generalizations, and there can be variations within each desert region. The specific characteristics can also vary depending on the exact location within California.