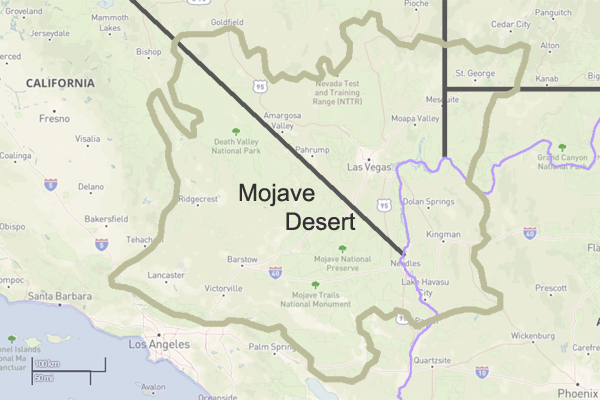

The most famous lost mine in the Death Valley area is the Lost Breyfogle. There are many versions of the legend, but all agree that somewhere in the bowels of those rugged mountains is a colossal mass of gold, which Jacob Breyfogle found and lost.

Jacob Breyfogle was a prospector who roamed the country around Pioche and Austin, Nevada, with infrequent excursions into the Death Valley area. He traveled alone.

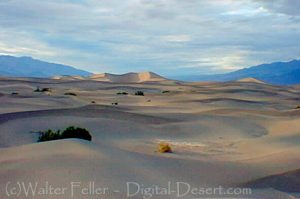

Indian George, Hungry Bill, and Panamint Tom saw Breyfogle several times in the country around Stovepipe Wells, but they could never trace him to his claim. When followed, George said, Breyfogle would step off the trail and completely disappear. Once George told me about trailing him into the Funeral Range. He pointed to the bare mountain. “Him there, me see. Pretty quick—” He paused, puckered his lips. “Whoop—no see.”

Breyfogle left a crude map of his course. All lost mines must have a map. Conspicuous on this map are the Death Valley Buttes which are landmarks. Because he was seen so much here, it was assumed that his operations were in the low foothills. I have seen a rough copy of this map made from the original in possession of “Wildrose” Frank Kennedy’s squaw, Lizzie.

Breyfogle presumably coming from his mine, was accosted near Stovepipe Wells by Panamint Tom, Hungry Bill, and a young buck related to them, known as Johnny. Hungry Bill, from habit, begged for food. Breyfogle refused, explaining that he had but a morsel and several hard days’ journey before him. On his burro he had a small sack of ore. When Breyfogle left, Hungry Bill said, “Him no good.”

Incited by Hungry Bill and possible loot, the Indians followed Breyfogle for three or four days across the range. Hungry Bill stopped en route, sent the younger Indians ahead. At Stump Springs east of Shoshone, Breyfogle was eating his dinner when the Indians sneaked out of the brush and scalped him, took what they wished of his possessions and left him for dead.

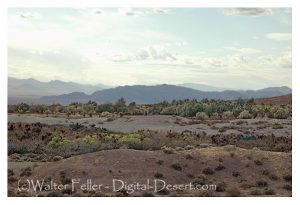

Ash Meadows Charlie, a chief of the Indians in that area confided to Herman Jones that he had witnessed this assault. This happened on the Yundt Ranch, or as it is better known, the Manse Ranch. Yundt and Aaron Winters accidentally came upon Breyfogle unconscious on the ground. The scalp wound was fly-blown. They had a mule team and light wagon and hurried to San Bernardino with the wounded man. The ore, a chocolate quartz, was thrown into the wagon.

“I saw some of it at Phi Lee’s home, the Resting Spring Ranch,” Shorty Harris said. “It was the richest ore I ever saw. Fifty pounds yielded nearly $6000.”

Breyfogle recovered, but thereafter was regarded as slightly “off.” He returned to Austin, Nevada, and the story followed.

Wildrose (Frank) Kennedy, an experienced mining man obtained a copy of Breyfogle’s map and combed the country around the buttes in an effort to locate the mine. Kennedy had the aid of the Indians and was able to obtain, through his squaw Lizzie, such information as Indians had about the going and coming of the elusive Breyfogle.

“Some believe the ore came from around Daylight Springs,” Shorty said, “but old Lizzie’s map had no mark to indicate Daylight Springs. But it does show the buttes and the only buttes in Death Valley are those above Stovepipe Wells.

“Kennedy interested Henry E. Findley, an old time Colorado sheriff and Clarence Nyman, for years a prospector for Coleman and Smith (the Pacific Borax Company). They induced Mat Cullen, a rich Salt Lake mining man, to leave his business and come out. They made three trips into the valley, looking for that gold. It’s there somewhere.”

At Austin, Breyfogle was outfitted several times to relocate the property, but when he reached the lower elevation of the valley, he seemed to suffer some aberration which would end the trip. His last grubstaker was not so considerate. He told Breyfogle that if he didn’t find the mine promptly he’d make a sieve of him and was about to do it when a companion named Atchison intervened and saved his life. Shortly afterward, Breyfogle died from the old wound.

Indian George, repeating a story told him by Panamint Tom, once told me that Tom had traced Breyfogle to the mine and after Breyfogle’s death went back and secured some of the ore. Tom guarded his secret. He covered the opening with stone and leaving, walked backwards, obliterating his tracks with a greasewood brush. Later when Tom returned prepared to get the gold he found that a cloudburst had filled the canyon with boulders, gravel and silt, removing every landmark and Breyfogle’s mine was lost again.

“Some day maybe,” George said, “big rain come and wash um out.”

Among the freighters of the early days was John Delameter who believed the Breyfogle was in the lower Panamint. Delameter operated a 20 mule team freighting service between Daggett and points in both Death Valley and Panamint Valley. He told me that he found Breyfogle down in the road about twenty-eight miles south of Ballarat with a wound in his leg. Breyfogle had come into the Panamint from Pioche, Nevada, and said he had been attacked by Indians, his horses stolen, while working on his claim, which he located merely with a gesture toward the mountains.

Subsequently, Delameter made several vain efforts to locate the property, but like most lost mines, it continues to be lost. But it was good bait for a grubstake for years and served both the convincing liar and the honest prospector.

Nearly all old timers had a version of the Lost Breyfogle differing in details, but all agreed on the chocolate quartz and its richness.

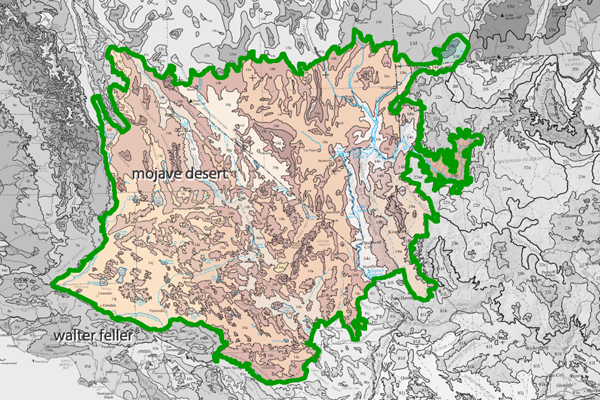

That Breyfogle really lost a valuable mine, there can be little doubt, but since he is authentically traced from the northern end of Death Valley to the southern, and since the chocolate quartz is found in many places of that area, one who cares to look for it must cover a large territory.