Brine flies at Mono Lake are one of those old, workmanlike desert stories where something humble ends up being essential.

Mono Lake is extremely salty and alkaline, so almost nothing can live there. Brine flies (Ephydra hians) are the big exception. They spend most of their lives as larvae and pupae underwater, grazing on algae that coat the lake bottom and tufa formations. When they emerge as adults, they form the dark, moving bands you see along the shoreline and rocks.

Their trick is simple but effective. Adult flies have dense hairs and a waxy coating that traps air around their bodies, allowing them to walk underwater to lay eggs and feed without drowning. It looks strange, but it works, and it has worked for a very long time.

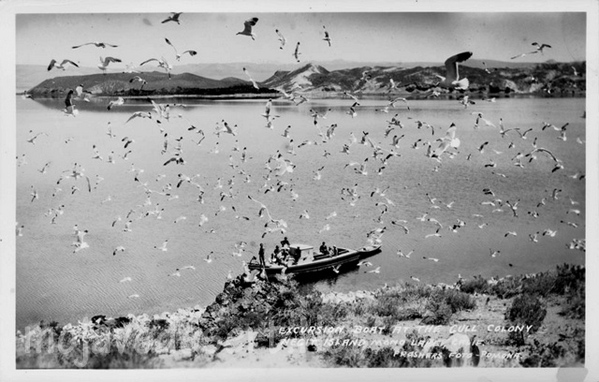

Ecologically, brine flies are the backbone of Mono Lake. They convert algae into protein, and in doing so, they feed millions of migratory birds. Eared grebes, phalaropes, gulls, and others depend on the flies during migration, sometimes doubling their body weight before moving on. If the flies disappeared, Mono Lake would be nearly silent.

Culturally, they mattered too. The Kutzadikaa Paiute, often called the Mono Lake Paiute, harvested brine fly pupae, dried them, and traded them as a high-protein food. Early Euro-American settlers mostly saw the flies as a nuisance, but the Paiute understood precisely what they were worth.

Today, brine flies are also an indicator species. When lake levels drop, and salinity rises too far, fly populations suffer. Keeping Mono Lake at a sustainable level is not just about scenery or tufa towers; it is about preserving this old, tightly balanced system that has been working more or less the same way since long before modern water diversions arrived.

-End-