The Pinto Basin and Mountains, located in Joshua Tree National Park in southern California, are notable for their rugged terrain, diverse geology, and rich history. Here’s an overview of the key aspects of this region:

Geography and Geology

Pinto Basin

- Location: The Pinto Basin is in the southeastern part of Joshua Tree National Park.

- Terrain: The basin is characterized by broad, sandy expanses interspersed with rocky outcrops and occasional washes.

- Geology: The basin’s geology is diverse, with ancient Precambrian rocks, including gneiss and schist, and recent sedimentary deposits. The basin’s alluvial fans are made of materials eroded from the surrounding mountains.

Pinto Mountains

- Location: The Pinto Mountains lie to the south of the Pinto Basin.

- Elevation: The mountains vary in elevation, with some peaks rising over 3,000 feet above sea level.

- Geology: The mountain range comprises various rock types, including granitic and metamorphic rocks, indicative of a complex geological history involving volcanic activity and tectonic movements.

History

Prehistoric and Native American Presence

- Pinto Culture: The region is named after the Pinto Culture, an early Native American group that inhabited the area around 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. Artifacts such as stone tools and points have been found, suggesting a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

- Native American Tribes: Various tribes, including the Chemehuevi and Cahuilla, lived in the region, relying on its resources for sustenance.

Historic Era

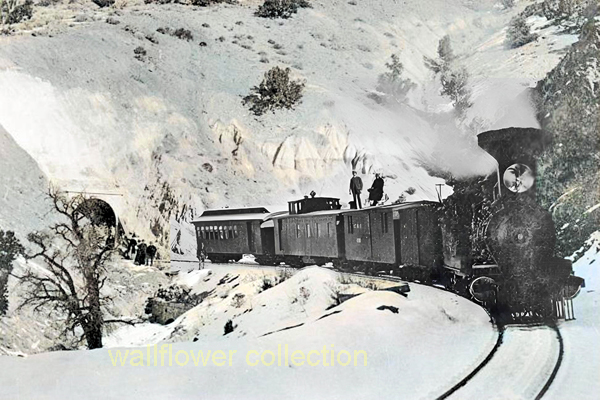

- Mining: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Pinto Basin and Mountains saw sporadic mining activity, primarily for gold and other minerals. Remnants of old mines and mining equipment can still be found in the area.

- Homesteading: In the early 20th century, homesteaders attempted to settle in the region, though the harsh desert environment made it challenging.

Flora and Fauna

- Flora: The Pinto Basin is home to various desert plant species, including creosote bush, Joshua trees, and ocotillo. The area’s unique ecosystem supports common and rare plant species adapted to the arid conditions.

- Fauna: The Pinto Basin’s wildlife includes desert bighorn sheep, coyotes, jackrabbits, and numerous bird species. Reptiles such as lizards and snakes inhabit the area.

Recreation and Attractions

- Hiking: The Pinto Basin offers several hiking opportunities, with trails ranging from easy walks to challenging backcountry routes. Popular trails include the Lost Palms Oasis and the Arch Rock Nature Trail.

- Scenic Drives: The Pinto Basin Road provides a scenic drive through the basin, offering stunning landscape views and access to various trailheads and viewpoints.

- Stargazing: The remote location and minimal light pollution make the Pinto Basin an excellent spot for stargazing and astrophotography.

The Pinto Basin and Mountains are a fascinating area within Joshua Tree National Park, offering visitors a glimpse into the natural and cultural history of the Mojave Desert.