THE OVERLAND MAIL

1849-1869

Promoter of Settlement

Precursor of Railroads by

LE ROY R. HAFEN, PH.D .

Historian, The Stale Historical and Natural History Society of Colorado

The first United States mail between California and Salt Lake City was established in 1851. This route was advertised January 27, 1851, and the thirty-seven bids received ranged from $20,000 for “horseback or two horse coach service,” to $200,000 per year for service with ” 135 pack animals with 45 men, divided into three parties.” One bid was for a four-horse coach with a guard of six men, at $135,000 per year. The lowest bid was accepted and a contract was made in April with Absalom Woodward and George Chorpenning for a monthly service at $14,000 per year; the trip each way was to be made in thirty days. No points were designated at which the route should touch, but it was to go “by the then traveled trail, considered about 910 miles long.”

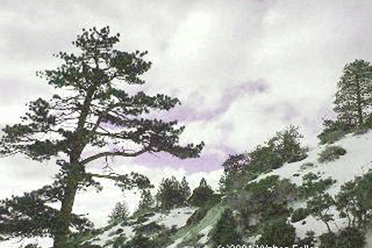

Chorpenning and his men left Sacramento May 1, 1851, with the first mail. They had great difficulty in reaching Carson valley, having had to beat down the snow with wooden mauls to open a trail for their animals over the Sierras. For sixteen days and nights they struggled through and camped upon deep snow. Upon reaching Carson valley, Chorpenning staked off in the usual western manner, a quarter section of land and arranged to establish a mail station. The town of Genoa, Nevada, grew-up on this site. Chorpenning and several men continued eastward and reached Salt Lake City June 5th, having been delayed somewhat by snow in the Goose Creek mountains.

Throughout the summer, difficulties were experienced with the Indians; and Woodward, who left Sacramento with the November mail, was killed by them just west of Malad River in northern Utah. The December and January mails from Sacramento were forced to return on account of deep snow, but the February (1852) mail was pushed through by way of the Feather River Pass and reached Salt Lake City in sixty days. The carriers endured frightful sufferings; owing to the fact that their horses were frozen to death in the Goose Creek mountains, they had to go the last two hundred miles to Salt Lake City on foot. Permission was obtained from the special agent in San Francisco to send the March mail down the coast to San Pedro and thence by the Cajon Pass and the Mormon trail to Salt Lake City. During the summer of 1852 the service continued to be performed across northern Nevada by way of the Humboldt River; but as winter approached, arrangements were made with the mail agent at San Francisco to carry the Utah mail via Los Angeles during the winter months. The Carson valley post office was supplied monthly by a carrier on snow-shoes. Fred Bishop and Dritt were the first carriers and they were succeeded by George Pierce and John A. Thompson. The latter, “Snowshoe Thompson,” a Norwegian by birth, made himself famous in this section by his feats on snow-shoes during succeeding winters. The shoes used were ten feet long and of the Canadian pattern. He often took one hundred pounds upon the journey between Placerville and Carson, and made the trip in three days to Placerville and the return journey in two days.

With the interruption by bad weather of the mail service east of Salt Lake City, the mail was sent westward to San Pedro, where it was transmitted by steamer to the Atlantic seaboard. This increased the weight of Chorpenning mail from about one hundred pounds to about five hundred pounds. For this additional service Chorpenning made claim and in 1857 received payment on a pro rata basis.

The causes of the irregularity and interruption of the mail service to Utah had not been explained to the Postmaster-general by the Special Agent at San Francisco and so, upon the grounds of the derangement of the service, the Postmaster-general annulled the contract with Chorpenning, and made one with W. L. Blanchard of California. The new contractor was to receive $50,000 per year, and was to maintain a fortified post at Carson valley. Upon learning of this new arrangement in January, 1853, Chorpenning set out for Washington and, after setting forth his case before the new Postmaster-general, was reinstated. A verbal agreement was made that the compensation should be increased to $30,000 per year and permission was given to carry the mails via San Pedro during the winter months.

During the first three years (1851-4) the Utah-California mail was carried except in winter, by the old emigrant route. This route lay from Sacramento

through Folsom, Placerville, along the old road through Strawberry and Hope valleys to Carson valley. From this point it led to the Humboldt, which stream

was followed nearly to its source. Leaving the Humboldt the route led northeastward into southern Idaho in the vicinity of the Goose Creek mountains, and thence southeasterly around the north side of Great Salt Lake to Salt Lake City.

In the lettings of 1854, the Utah-California mail route was changed to run from Salt Lake City over the Mormon trail to San Diego. Chorpenning was again the successful bidder. The mail was to be carried monthly each way, through in twenty-eight days, for a compensation of $12,500 per year. Chorpenning thought it worthwhile to enter a low bid to ensure getting the contract since he expected that the service would probably be increased to a weekly schedule, the time per trip reduced, and the compensation increased.

The service began July 1, 1854, and was to continue for four years. The mail was carried on horseback or on pack mules. During that first summer, Indian difficulties arose and continued at intervals for months. The emigration fell off and expenses on the route increased. Similar difficulties had been encountered by the contractors east of the Rocky Mountains, who appealed to Congress and received increased remuneration by the act of March 3, 1855. Encouraged by their success with Congress, and inasmuch as his difficulties continued, Chorpenning went to Washington and presented his claims in June, 1856. Congress responded with an act for his relief March 3, 1857. It provided that the compensation be increased to $30,000 per year from July 1, 1853, to the termination of the contract in 1858; that the full contract pay be allowed during the suspension of the contract in the spring of 1853; and that the Postmaster-general make an additional allowance on a pro rata basis for the extra service performed prior to 1853. A total of $109,072.95 was allowed and paid under the provisions of this act.

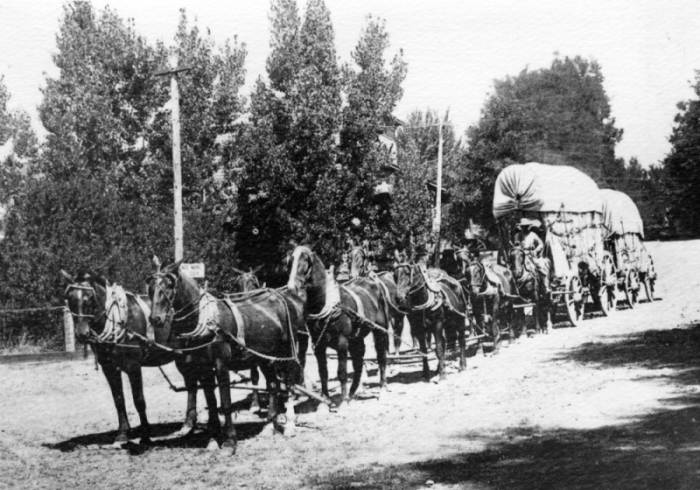

During the four years of the duration of the contract (until July i, 1858), the mail was carried with fair regularity, and often in less than schedule time. The service was usually performed on horseback, but a wagon was used occasionally. The mail of December, 1857, was taken from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles by wagon in twenty-six days, while on horseback the trip often did not consume more than twenty days.

Wells Fargo and Company, Adams and Company, and other express companies maintained express service on the line during this period (1854-8). There was also much freighting and some emigrant travel over the road. The Mormon “State of Deseret” had included the whole of this route with its terminus upon the Pacific Coast. A colony was planted by these pioneers at San Bernardino in 1851 and considerable trade and intercourse was carried-on over this road.

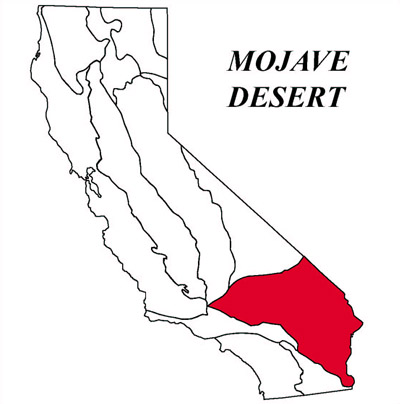

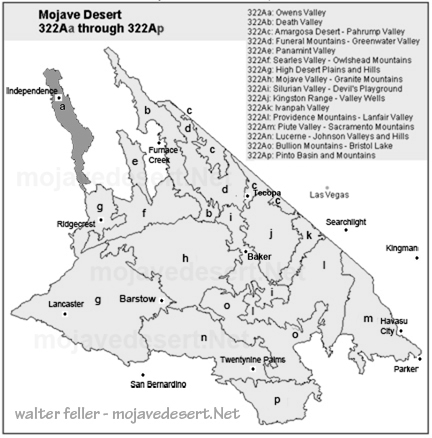

The route was in general that of the present “Arrowhead Trail” automobile road. From Los Angeles the route led to San Bernardino, through Cajon Pass to the Mohave River, which was followed for fifty miles. From the Mohave River the route lay to the north to Bitter Springs, then turned eastward by Kingston Springs to Las Vegas, Nevada. From this famous resting station a dry stretch of sixty miles was crossed leading to the Muddy Creek. After crossing another “bench” the Virgin River was reached, and this stream was followed to Beaver Dams, Arizona. Leaving the Virgin River the road crossed the “slope” and over a little mountain range to the Santa Clara Creek, which stream was followed to the vicinity of the famous Mountain Meadows. From Mountain Meadows the route led to Cedar City and thence almost due north through the Mormon settlements of Parowan, Beaver, Fillmore, Nephi, Payson, Provo, and Lehi to Salt Lake City.”

Before the termination of the contract on this route the policy of extensive increases in the western mail lines was inaugurated, and partisans of the “Central Route” via Salt Lake City and across northern Nevada were demanding service upon that more direct route to San Francisco. Accordingly, in 1858 this Los Angeles to-Salt Lake City route was discontinued and the original route of 1851 was re-established and put upon an improved basis.

–