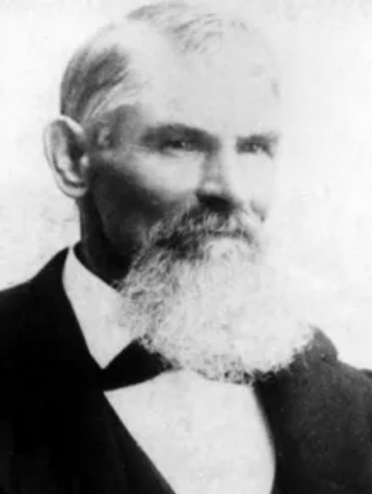

Johann George Ecker led a group of German and Swiss immigrants who settled in the Antelope Valley in 1886, founding a small colony they called Palmenthal—named for the nearby Joshua trees, which they mistook for palms. These settlers sought to establish a self-sufficient farming community on the high desert plain. Drawing from their European roots, they introduced cooperative labor, community organization, and dry-farming methods suited to the arid conditions. Early crops included barley, wheat, and fruit orchards, with irrigation ditches dug by hand to capture scarce water. Despite their determination, drought and isolation made survival difficult, and by the early 1890s, many settlers left. Still, their legacy endured in the renamed settlement of Palmdale, marking the valley’s first organized agricultural community.

Palmenthal was the original German-Swiss settlement that became Palmdale, California. Founded in 1886 by Johann George Ecker and a group of immigrant families from Germany and Switzerland, the colony was located near present-day 20th Street East and Avenue Q. The settlers named it Palmenthal, or “Palm Valley,” after mistaking the native Joshua trees for palms.

They arrived with hopes of building a cooperative farming community, bringing European agricultural practices and traditions with them. Using dry-farming methods, they planted barley, wheat, and fruit orchards, and attempted small-scale irrigation projects to make the desert productive. The settlers built simple homes, a school, and community facilities, establishing the first structured settlement in the Antelope Valley.

Life in Palmenthal was harsh. Repeated droughts, crop failures, and the isolation of the high desert took their toll. Within a few years, many families abandoned the colony, some moving closer to the Southern Pacific Railroad line near Harold, where water and transport were more reliable. By the early 1890s, Palmenthal was largely deserted, but its spirit persisted in the nearby settlement that would evolve into modern Palmdale.

The story of Palmenthal represents the first organized effort to colonize and cultivate the Antelope Valley—an experiment in community and endurance that laid the groundwork for future growth in the region.

Timeline

1886 – Johann George Ecker and a group of German and Swiss immigrants establish the settlement of Palmenthal in the Antelope Valley, naming it for the Joshua trees they mistake for palms.

1887 – The settlers begin dry farming and plant wheat, barley, and fruit orchards. A small schoolhouse and community hall are built.

1888 – Severe drought conditions make farming difficult. Wells yield limited water, forcing the settlers to haul water from distant springs.

1889 – Some families leave the settlement due to crop failures and the isolation of the high desert.

1890 – Remaining settlers attempt to improve irrigation by digging ditches and small reservoirs, but lack of rainfall continues to hinder success.

1891 – The Southern Pacific Railroad establishes a station several miles west, prompting some settlers to relocate closer to the line for better access to supplies and transport.

1892 – Palmenthal is largely abandoned. The remaining residents consolidate around the new rail siding area that becomes known as Palmdale.

1893 – The name Palmdale replaces Palmenthal, marking the transition from the failed colony to the town that would endure.