Many folks interested in Mojave Desert history are aware that in 1776, Francisco Tomás Hermenegildo Garcés was the first non-native American to cross the Mojave from the Mojave Indian villages near Needles at the Colorado River to the Mission San Gabriel near Los Angeles, California. Trapper and explorer Jedediah Smith also crossed the Mojave in 1826 and in 1827.

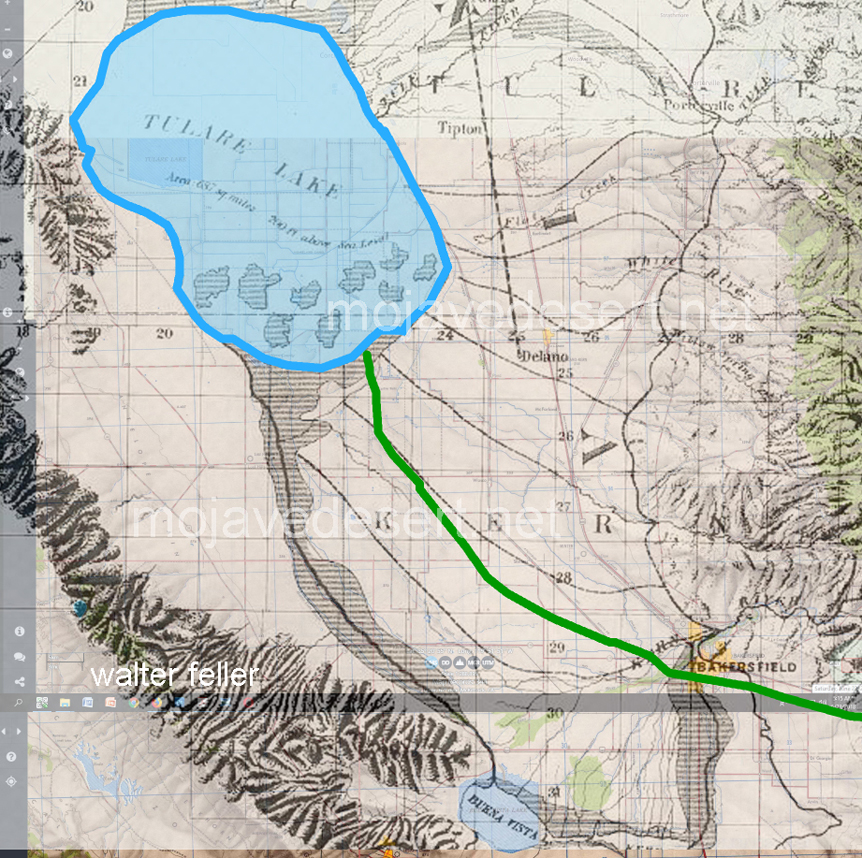

Tulare Lake – 1874

Not so well known is that when they left the mission at San Gabriel, both men made their way north to the San Joaquin Valley and the shore of Tulare Lake. In tracking the paths of both men concerning our modern geography, it is soon discovered that this lake does not seem to exist.

What happened to Tulare Lake?

The answer to this mystery of a disappearing lake is simple yet inelegant and predictable:

At the onset of American settlement in the area in the late 1840s, the lake was the largest body of fresh water west of the Great Lakes. Its destruction by the late 1800s because of diking and water diversion for irrigation was one of the most dramatic signs of a major theme in the state’s history: the rapid transformation of the wild California landscape into one dominated almost completely by human action.

From Report of the Board of Commissioners on the Irrigation of the San Joaquin, Tulare, and Sacramento Valleys of the State of California.

Tulare Lake Satellite Overlay 2018

So, now you know.