When people think of Big Bear Lake or Littlerock Reservoir, they usually picture pine-covered hills or quiet desert canyons. But beneath those scenic views lie stories of bold ideas, early 20th-century innovation, and one man who didn’t mind going against the grain: John S. Eastwood.

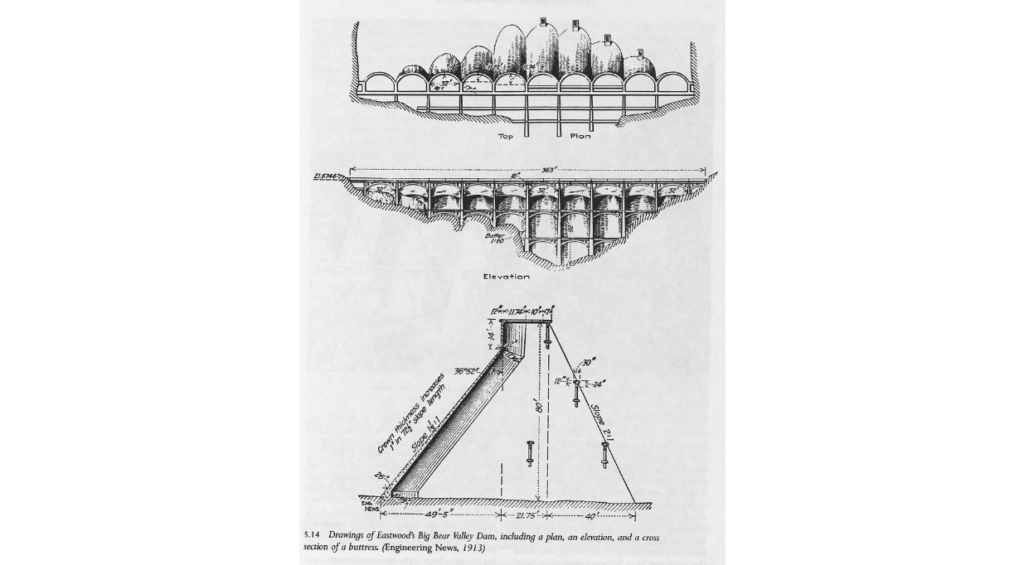

Eastwood wasn’t interested in building dams the way everyone else did. While most engineers were busy stacking massive concrete walls straight across rivers, he had something different in mind: a system of thin, curved arches that transferred pressure into solid rock abutments. It was lighter, cheaper, and—in his view—smarter.

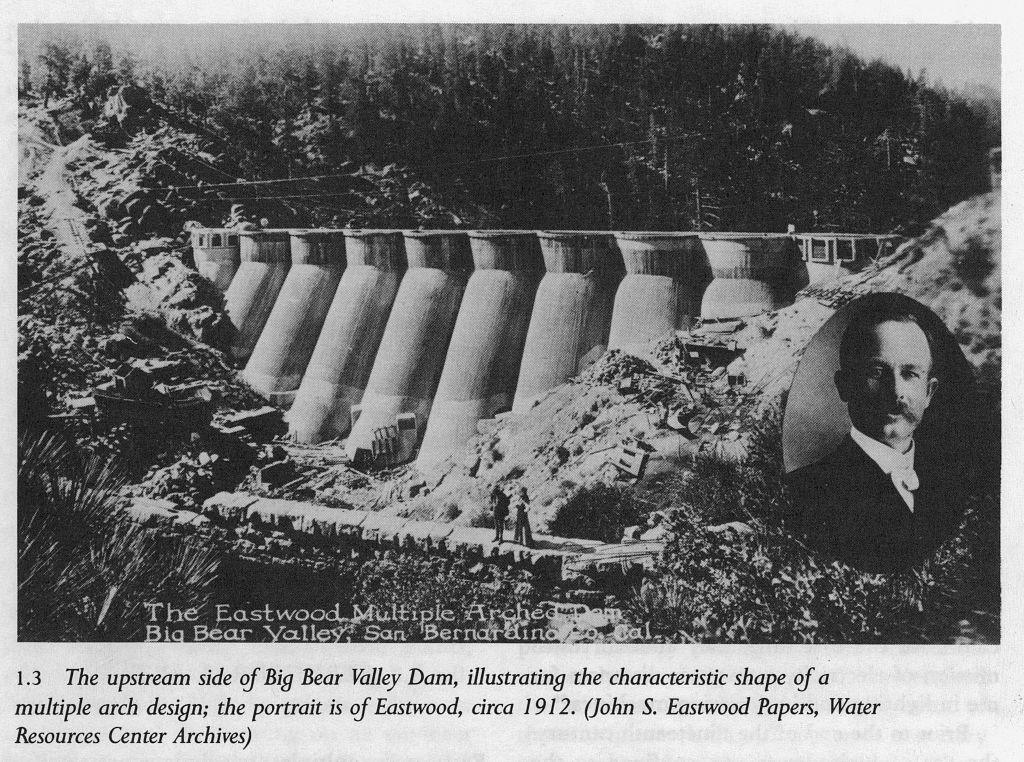

In Big Bear, the original dam dated back to 1884. It was built by Frank Elwood Brown, a man with a vision to turn the dry, chaparral-covered inland valleys into citrus groves. His dam was modest and practical for its time, but growing demand soon outpaced its capacity. By 1910, the Bear Valley Mutual Water Company called on Eastwood to design something new. What he gave them in 1912 was a graceful structure of eleven concrete arches—his signature multiple-arch style. It raised the lake level and helped feed the thirst of the San Bernardino Valley below. A bridge was added in 1924, making the dam a true link between the north and south shores and turning it into a local landmark.

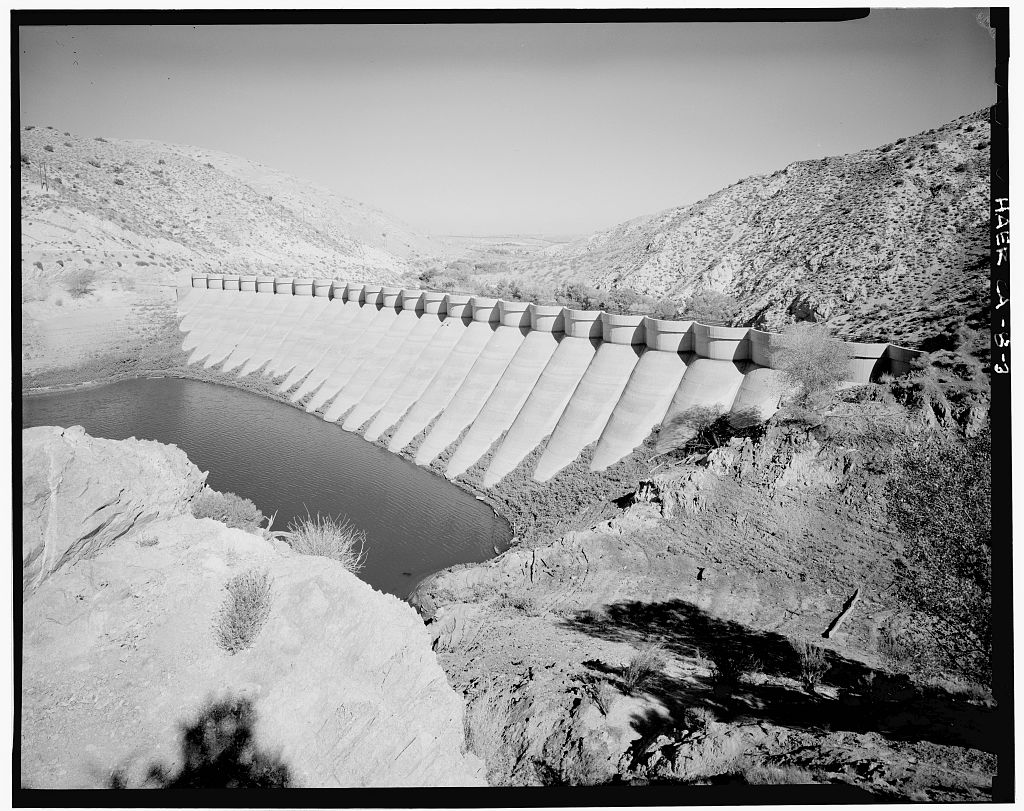

Meanwhile, about 60 miles west as the crow flies, the Littlerock Dam rose in a very different landscape—dry, wide-open desert edged by the San Gabriel Mountains. Built between 1922 and 1924, the dam had a job to do: tame seasonal flooding and store water for nearby farms and growing communities in the Antelope Valley. Again, Eastwood’s multiple-arch design was chosen. At the time of its completion, Littlerock Dam was the tallest structure of its kind in the world. It stood not just as a practical solution but also as a quiet sign of faith in human ingenuity—a way to harness nature without bulldozing over it.

Over the years, both dams have been modified to meet modern standards. Littlerock was reinforced in the 1990s, its delicate arches now hidden beneath a face of roller-compacted concrete. Some of Eastwood’s original elegance was lost, but the structure still holds firm. Big Bear’s dam remains more visibly true to his vision, standing quietly beside the lake like a relic from a time when ambition was poured in concrete.

John S. Eastwood may not be a household name, but his work left a lasting mark on California’s landscape. His dams in Big Bear and Littlerock weren’t just about holding back water—they were about pushing engineering forward. More than a century later, their presence still shapes the way people live, work, and play in the Mojave and San Bernardino Mountains.

Eastwood wasn’t interested in building dams the way everyone else did. While most engineers were busy stacking massive walls of concrete straight across rivers, he had something different in mind: a system of thin, curved concrete arches that would transfer pressure into solid rock abutments. It was lighter, cheaper, and—in his view—smarter.