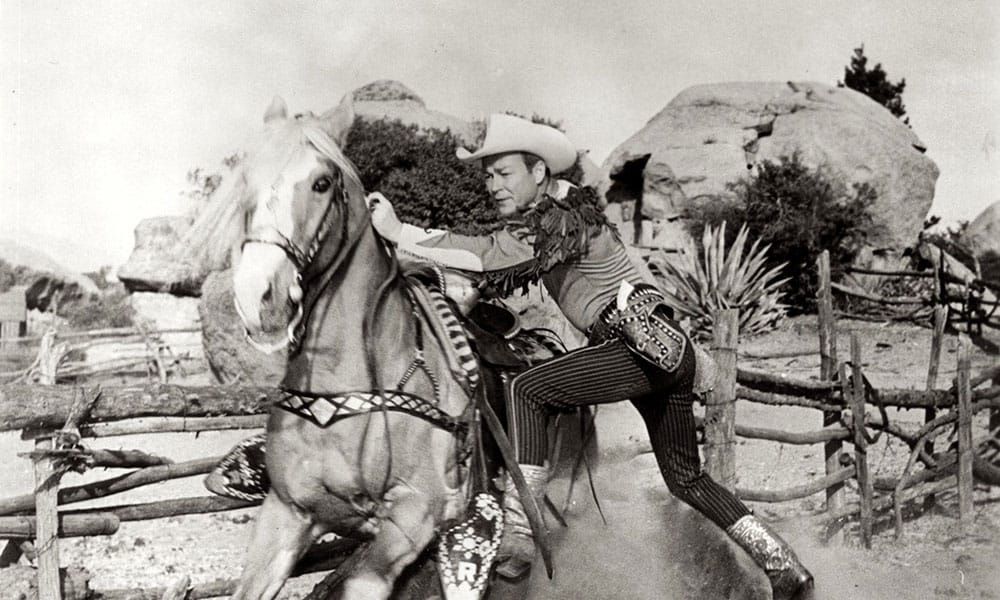

Trigger was the famous horse ridden by Roy Rogers, the iconic American cowboy actor and singer. Trigger was a golden palomino known for his intelligence, versatility, and striking appearance. He became one of the most well-known and beloved horses in the history of Hollywood.

Trigger was a Palomino horse that became famous as the faithful companion of Roy Rogers, a popular American cowboy actor and singer. Trigger was born in 1932 and originally named Golden Cloud. Roy Rogers first encountered the horse in the 1938 movie “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” where Olivia de Havilland rode him.

Impressed by the horse’s beauty and abilities, Rogers eventually acquired him. The horse was then renamed Trigger, and he became one of the most famous horses in Hollywood history. Trigger appeared in many of Roy Rogers’ films and television shows, showcasing his remarkable intelligence and performing various tricks on command.

Trigger appeared in many of Roy Rogers’ films and television shows, becoming a true partner to Rogers in his on-screen adventures. The horse was trained to perform a variety of tricks and stunts, showcasing both Trigger’s abilities and the strong bond between him and Rogers.

Trigger became a beloved icon, often called “The Smartest Horse in the Movies.” After Trigger died in 1965, Rogers arranged for the horse to be taxidermied. The preserved Trigger was displayed at the Roy Rogers and Dale Evans Museum in California. Later, the museum closed, and in 2010, Trigger was sold at auction for nearly $266,000. The buyer, a cable television network, intended to use the preserved horse in a planned Roy Rogers exhibit.

Trigger’s legacy lives on in fans’ memories and the numerous films and television shows where he played a prominent role alongside Roy Rogers.