Introduction

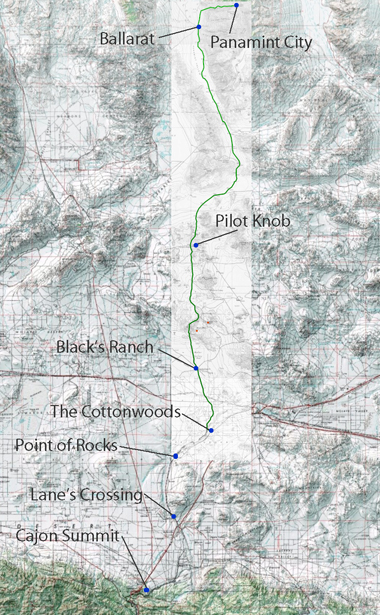

Nestled within the rugged landscapes of Eastern California, the Panamint Valley is home to a historical artery that has played a pivotal role in developing the American West—the road to Panamint. Originally trodden by Native Americans and later transformed by the ambitions of silver miners, this route not only facilitated economic booms but also bore witness to the ebbs and flows of fortune. The road to Panamint is a testament to the region’s mining era, epitomizing the broader transportation infrastructure development crucial for westward expansion.

Historical Background

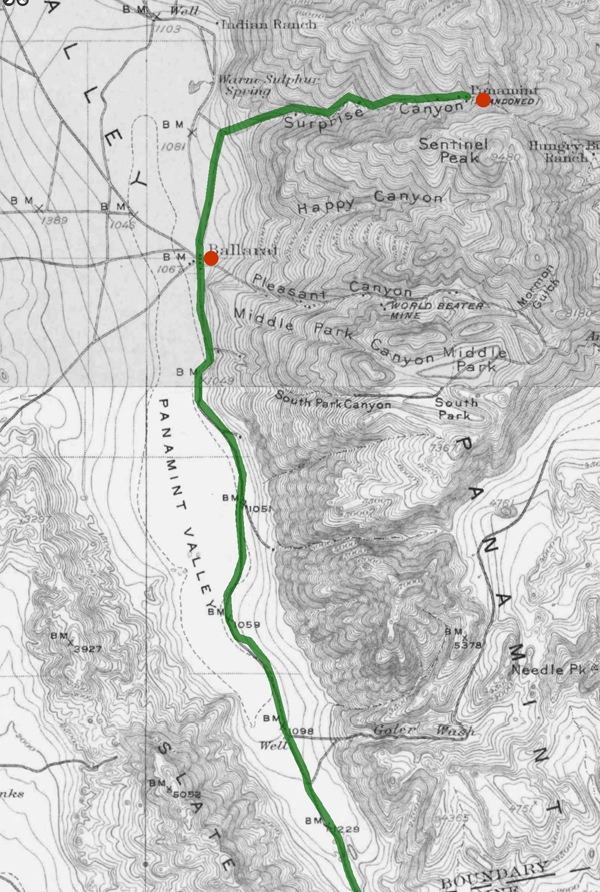

The Panamint Valley, framed by the arid peaks of the Panamint Range, was first utilized by the Shoshone Native Americans, who traversed these harsh landscapes following seasonal migration patterns and trade routes. The discovery of silver in 1872 marked a turning point for the valley. News of silver attracted droves of prospectors, catalyzing the establishment of mining camps and the nascent stages of the road. This road would soon become the lifeline for a burgeoning settlement, later known as Panamint City.

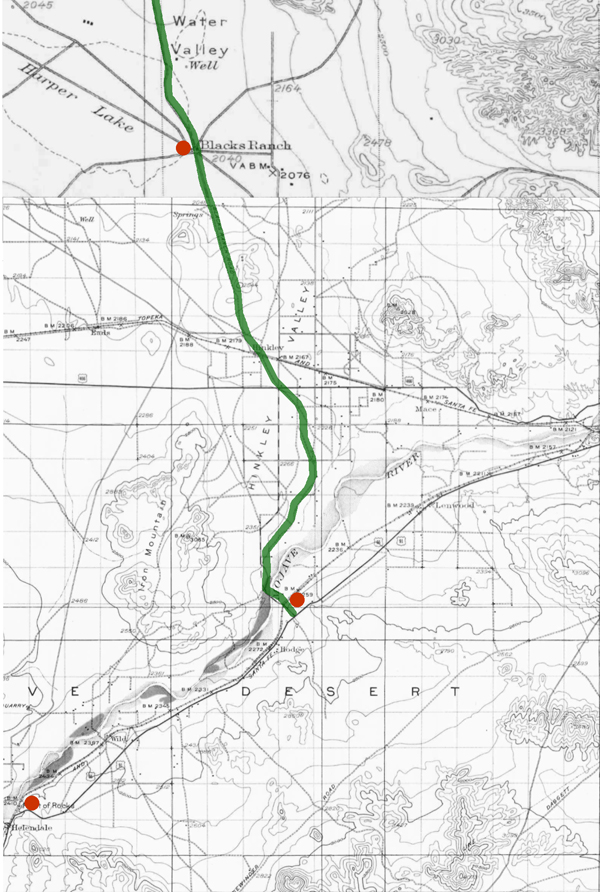

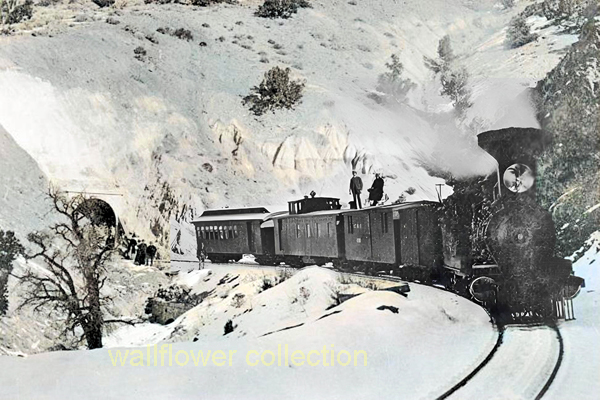

Development of the Road

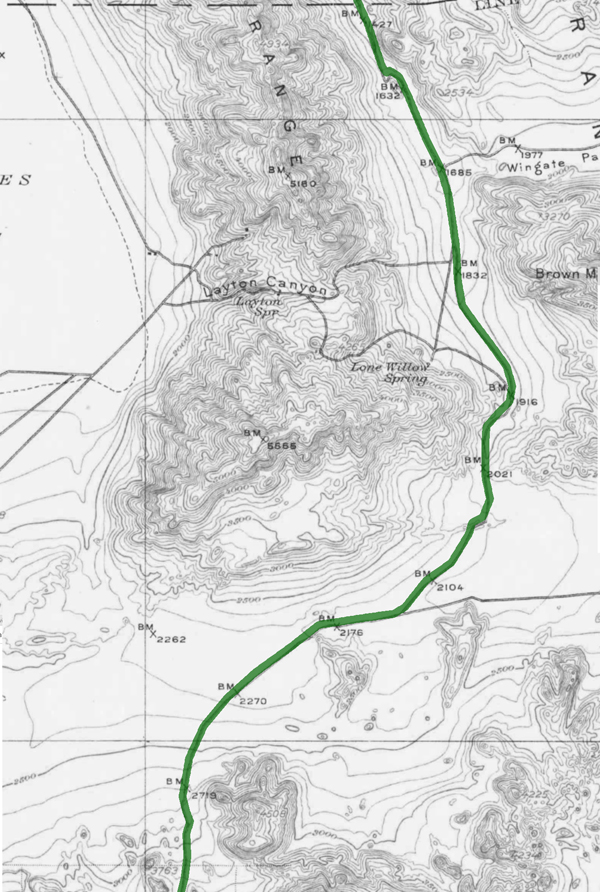

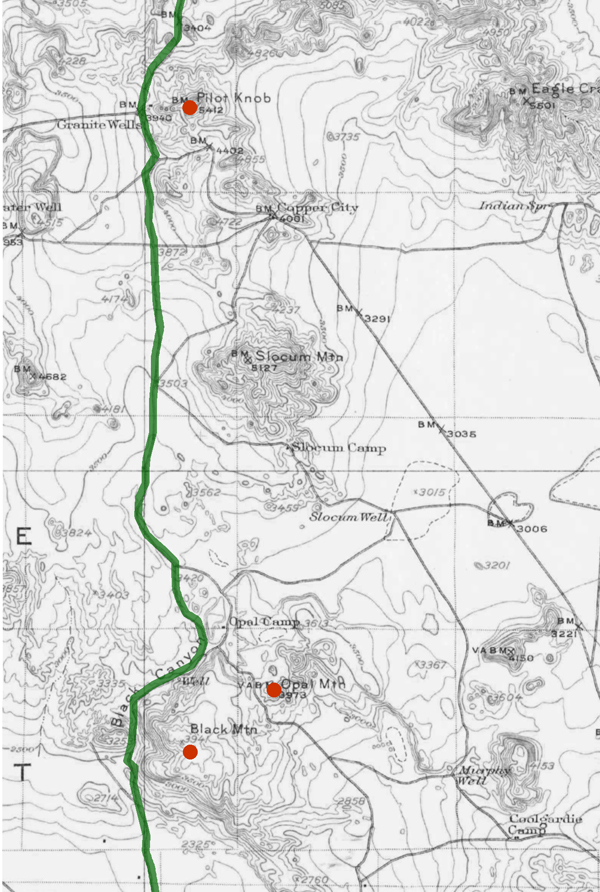

The transformation from a series of Native trails to a fully functional road was propelled by the mining industry’s explosive growth. As prospectors and entrepreneurs flooded the area, the demand for a reliable transportation route skyrocketed. The road to Panamint was quickly carved out of the valley’s rugged terrain, facilitating the movement of people and ore. During the mid-1870s, Panamint City blossomed into a boomtown, with the road being crucial for transporting silver ore to markets beyond the valley. However, as the mines depleted and profits dwindled, the road witnessed the departure of those who had come seeking fortune, leaving behind ghost towns and tales of a fleeting era.

Significance in Regional History

Beyond its economic contributions, the road to Panamint played a significant role in shaping the regional history of Eastern California. It facilitated the integration of remote areas into the state’s broader economic and cultural fabric. Moreover, it was a stage for several historical events, including conflicts between Native Americans and settlers and among competing mining companies. The road connected Panamint with the outside world and helped establish transportation routes that would later support the growth of other regional industries and settlements.

Preservation and Legacy

Today, the road to Panamint is a shadow of its former self, yet it remains an integral part of the cultural heritage of the American West. Efforts have been undertaken to preserve its historical significance, recognizing the road as a physical pathway and a historical document inscribed upon the landscape. It is featured in historical tours, providing insights into the challenges and triumphs of those who once traveled its length in pursuit of silver and survival. The preservation of this road allows contemporary visitors and historians alike to traverse the same paths miners once did, offering a tangible connection to the past.

Conclusion

The road to Panamint encapsulates the spirit of an era driven by the quest for precious metals and the relentless push toward the West. Its historical importance remains a key narrative in understanding how transportation helped shape the economic and cultural landscapes of the American West. As we reflect on its legacy, the road to Panamint continues to offer valuable lessons on resilience and the transient nature of human endeavors.