Introduction:

The Victor Valley, located in Southern California, is often hailed as a vibrant and promising region. Its picturesque landscapes, growing economy, and close proximity to major cities make it an attractive destination for many. However, in this blog post, we will explore a different viewpoint – that of a pessimist. By examining the potential drawbacks and challenges faced by the region, we aim to offer a contrasting perspective on the Victor Valley.

1. Economic Challenges:

Despite its apparent economic growth, the Victor Valley faces several challenges that a pessimist would highlight. The region heavily relies on a few industries, such as agriculture and tourism, which leaves it vulnerable to fluctuations in these sectors. Furthermore, the lack of diversification in the job market can lead to higher unemployment rates during economic downturns, leaving many residents struggling to make ends meet.

2. Infrastructure and Public Services:

From a pessimist’s viewpoint, the Victor Valley’s infrastructure and public services are not without their shortcomings. The area’s rapid population growth has strained the existing road networks, leading to congestion and longer commuting times. Additionally, public transportation options are limited, making it difficult for residents without private vehicles to navigate the region. Moreover, the availability and quality of essential services, such as healthcare and education, may not meet the demands of the growing population.

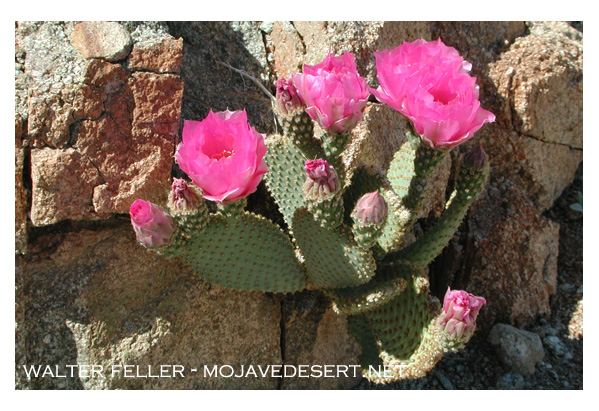

3. Environmental Concerns:

The pessimist’s perspective also sheds light on the environmental challenges faced by the Victor Valley. As the region continues to develop, it risks encroaching upon natural habitats and disrupting local ecosystems. The demand for water, in particular, poses a significant concern, as the Victor Valley is located in a semi-arid region with limited water resources. Excessive groundwater extraction and inadequate water management practices could have long-term consequences for the region’s sustainability.

4. Limited Cultural and Recreational Options:

Contrary to the popular perception of the Victor Valley as a vibrant cultural hub, a pessimist might argue that the region lacks diverse cultural and recreational opportunities. The area’s limited investment in arts, entertainment, and recreational facilities may leave residents with fewer options for leisure and personal growth. As a result, the Victor Valley may struggle to attract and retain young professionals and families seeking a well-rounded lifestyle.

Conclusion:

While the Victor Valley undoubtedly offers many benefits and opportunities, it is essential to consider the pessimist’s viewpoint to gain a well-rounded understanding of the region. By acknowledging the economic challenges, infrastructure limitations, environmental concerns, and cultural and recreational limitations, we can foster a more comprehensive dialogue about the future of the Victor Valley. It is through such discussions that we can work towards addressing these issues and ensuring a more balanced and sustainable future for the region and its residents.