BY CHRIS KASTEN

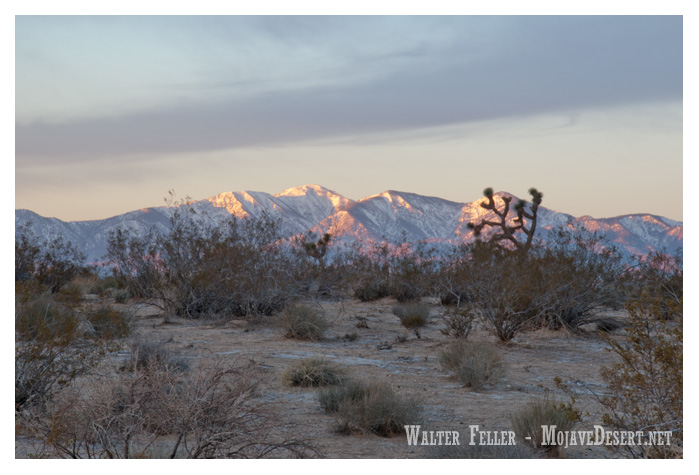

Hike Mount Baldy to Wrightwood via the North Backbone Trail. This trip takes you from south to north, traversing the San Gabriel mountains eastern high country. The terrain is high and dry, passing amongst wind bent pines, colorful outcroppings of rock, and views in all directions while taking you through stunning alpine scenery.

Total Distance = Approx. 12 miles one way

Initial Elevation Gain = 3,900′ the first 4 miles to Mt Baldy. Once on the North Backbone trail, which’ll take off northward at the 10,064′ summit, there is an initial 1,300′ of steep descent down to the first saddle. Next there’s 900′ of climb to Dawson Peak followed by 400′ of drop to the next saddle. Finally there’s a brief climb of 450′ to the gentle summit of Pine Mountain. Now and finally, there’s a good 1,400′ drop down to the last little saddle before climbing up a couple hundred yards to the end of the North Backbone trail. In another 1 1/2 miles of level trail walking you’ll reach the upper end of the Acorn Trail where there will be 1,600′ of drop into Wrightwood. Over the length of this hike your total Gain will be 5,250′ and the total DROP will be 4,700′.

Map to take: Tom Harrison’s “ANGELES High Country” map, 2018. Nothing against map apps, I just happen to really like having a physical map as well as bringing an orienteering compass, too.

This last Monday, my wife and I drove around to San Antonio Canyon above Upland, from our home in Wrightwood. I’d been thinking about hiking up Mt. Baldy from the U.S. Forest Service Manker Flat campground and had been kicking this idea around for about a week. As some days went by, got to thinking that it’d be really nice to just keep on hiking from Baldy’s summit to Wrightwood via the North Backbone trail. Easy, speasy.

All of this area, including the North Backbone trail, I had hiked years earlier, meaning in some cases, some decades ago… It all seemed so easy in my head and being that it was only going to be a day hike, there wouldn’t be a heavy pack to lug up and down the ridge tops. That’s it, a cinch! I’m now pushing 59 years and still hiking, yet there’s no denying that the hikes take a wee bit longer and the recovery the day after is longer . Yeah. Well, as things turned out, we got started a bit later than planned, meaning like almost 11:00 a.m. Nonetheless, it ended up being a great day to hike! My wife was going to drop me off at the Manker Flat trailhead and we’d meet up later in Wrightwood.

I’d wanted to show Joanie San Antonio Falls, which she’d never seen before, and peer down at some of the little cabins hidden along the little creek. This meant walking the gated fire road, which is unfortunately paved, up to its’ first switchback at the base of the falls. It can be sort of hot and exposed, like it was the day we went. Still it was worth seeing the Falls. We said our goodbyes out under the bright blue sky and off I climbed up the fire road which had now become dirt. It’d be some ten hours before we’d meet up, again, on the other side of the range in Wrightwood.

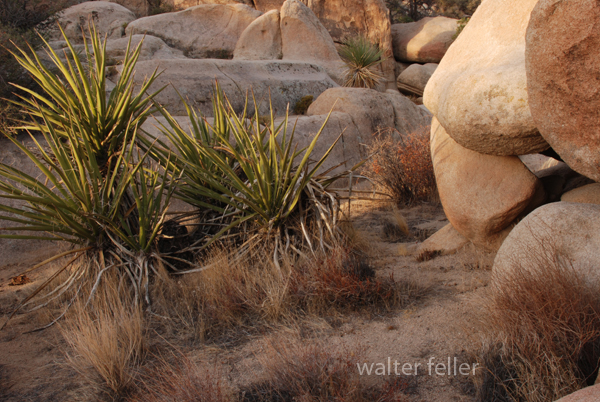

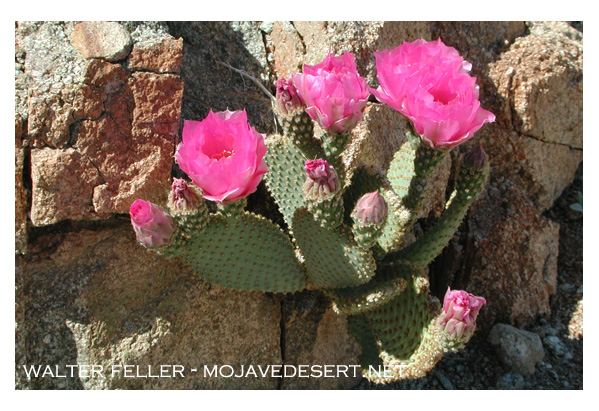

The turn off for the Baldy Bowl trail came up quickly on my left. That’s where the work began. Two things that came to mind and became readily apparent in no time at all was: 1. How much steeper the trail was than I had remembered it and 2. Just how big Mt. Baldy really is, no matter which way you go up it. It’s really a tall, broad mountain, especially by Southern California standards. Throughout the climb, despite the frequent standing up rests to slow the heart down and catch my breath, it was absolutely beautiful looking out over rugged San Antonio canyon. The trail climbs quickly up through oaks, mountain mahogany, manzanita and of course, shading pines and white fir. Just before reaching the Baldy Bowl, named by early x-country skiers in the early 20th century, you pass under the Sierra Club’s ski hut. Available to overnight stays by reservation only, this place is meticulously maintained and obviously loved by the membership. No one was there that day and I just kept hiking along, grateful for the icy cold stream that lay just moments ahead. There are strips of meadow flowers hugging the stream banks both below and above the trail. Flowers and willows crowded together along the tumbling, silver thread of water. The section where the trail crosses through the bowl is a complex of boulders, many the size of small cabins. It’s slow going and requires taking your time to read the trail, watching for clues as to where to meander next. Constantly, there was this sense that I was in the Sierras, and yet, somehow this San Gabriel mountains scenery felt, looked and even had that scent of Sierra rock and pine. All too soon, the trail leaves the Bowl and begins to switchback up through Jeffrey and Ponderosa pines. Soon the lodgepole pines began to make their presence and so did someone else.

It had been years since seeing a bighorn sheep. Like always, it was never my eyes that would detect these elusive creatures. The sound of a few pebbles breaking loose from the hillside caught my attention and there she was! A few minutes later, another ewe peered at me from behind a fallen tree. She and her lamb were grazing on about a 45 degree slope on the edge of the Bowl. A double gift for sure. Occasionally I’d stop at the end of a switchback and take in the changing view of the ridge line (Devil’s Backbone) coming in from Baldy Notch. By now I’d reached the broad ridge top defining the west side of Baldy Bowl, the immense scale of the smooth talus slope dropping steeply off the south side of the summit had become apparent. The trees, pretty much all lodgepole, were twisted and sculpted by the centuries of storms blowing in off the Pacific.

One thing that really caught my eye along the whole route were the really well made and maintained trail signs. Not only are there good directional signs along the way, there are even square steel posts with reflective tape on them, often giving you a good sense of where the trail would be should it be dark or there be a mantle of snow on the ground. This trail has really been well thought out. Another detail that became subtly apparent after some time was the lack of litter. My route was especially pristine and free of trash. There’s definitely a sense of stewardship going on up here. I hadn’t brought a watch, so never did determine just when I summited. That was purposeful and there was this wonderful relief at not having to know. Probably at least several hours had elapsed before making it to the top. There were probably no more than a dozen people sharing the trail up to the top that day. Really peaceful. Found a spot near the summit marker (elev. 10,064′) to sit down on my tired haunches, looking out to the north and down into the Fish Fork.

While taking in the view, a fit 30 something man with a solid build and neatly cropped red beard approached, asking if he wasn’t spoiling my solitude. Of course not! Pull up a boulder and sit down. Pretty soon I learned where he’d been, as his IPA cracked open and quickly vanished. Sam had started out at the Heaton Flat trailhead way down in the East Fork before heading up to Iron Mountain, one of the most isolated and difficult peaks to reach. From there, he worked his way across West San Antonio Ridge to the summit of West Mt. Baldy. From here, he’d drop down to Manker Flat and find his hidden mountain bike and take that back to his car by pedaling over the Glendora Mountain Ridge Road! That’s the caliber of company you can sometimes run into on higher peaks… Soon I was off and heading down the North Backbone Trail toward Blue Ridge and Wrightwood beyond. Gotta tell you, taking trekking poles was one of my best moves of the day. The descent was extremely steep down to the first saddle north of Mt. Baldy. Spots where I definitely would have slipped just from fatigue, were pretty easily walked down with the aid of the poles. This is a trip where you’d be glad to have a set of them.

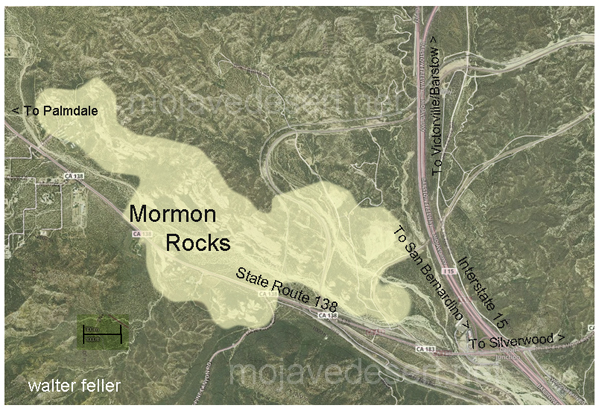

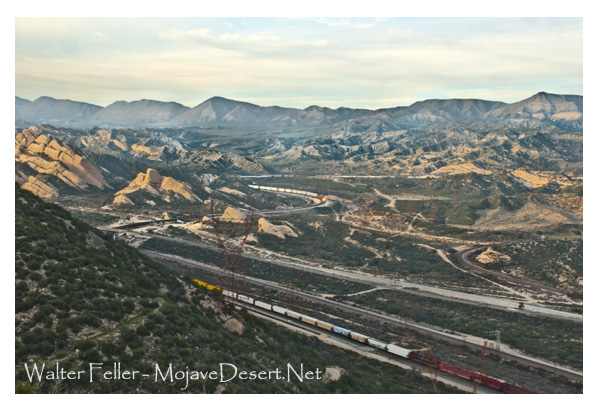

The climb up to Dawson Peak went well. There’s lots of rabbitbrush along the way. The trail weaved in and out of the thick yellow blossoms, giving the late afternoon light a feeling of autumn. Mountain mahogany and twisted rock outcroppings kept things interesting as well. There was a great view down toward the Cajon Pass with commuters making their sluggish drive back toward the desert. A freight train could be seen climbing the serpentine railroad tracks as well, tiny in comparison to the arid landscape. All this activity was silent, visible, yes, yet no sound whatsoever. To my left, grand scenes of the Fish Fork and Mount Baden Powell, continued to dominate my senses. A refreshing and constant breeze out of the west kept me cooled down. Once on top of Dawson (elev. 9,575′), I signed the summit register and continued on down a gentle descent through sun – polished plates of schist. Talus, I suppose. Beautiful stuff that sounded like ceramic dinner plates clunking together under my boots at times. There were even these beautiful, hidden, forested and shaded flats just below the trail at times, spots that would make for a perfect campsite. Untouched. Just before reaching the saddle between Dawson and Pine Mountain, I saw the old and seemingly untrammeled Fish Fork Trail coming in from my left.

There’s even an old graying wooden sign indicating the way down. I’ve always wanted to follow this trail which drops down to Fish Fork trail camp, probably one of the most isolated haunts in our range. That old feeling came back somewhat suddenly, mixed with wonder at how good things still are in the backcountry here. Pristine. And since it’s hard to get to, at least for me, nothing’s trashed. A constant truth throughout the ages. Thank God. Amen.

Soon I was climbing yet, again. This time it was up to Pine Mountain (9,648′). Weaving amongst more pines and mountain mahogany, the sun continued to drop further and further down across the mountains, casting longer and longer shadows in the gentle wind. Up on top, the summit register of nested red cans was easily found in a cairn of rocks. The desire to linger here awhile longer was resisted by the nagging feeling to at least get to Blue Ridge and the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) before it got dark. So, reluctantly, off I dragged my now tired self down a gentle slope amongst a thick forest of lodgepole pine. The deepening pools of shade penetrated the forest in a way that reminded me of being a little boy, maybe six or seven, running through the giant sequoias where our family used to camp every summer in a tent cabin. I missed people that I hadn’t thought about in awhile. They all came back for a bit and I reveled in this.

After a short while, the ridge top timber all but left, becoming a sharp edged knife of rock, bathed in orange golden sunlight. Take your time here, Chris, something kept gently telling me. I was tired and starting to get sloppy, not quite so nimble as hours earlier. Eventually the ridge got easier and right before sun had set below the horizon, a beam of that gold light struck some dangling cones hanging from an ancient sugar pine. This hike kept getting more and more gorgeous, nostalgic in a way. In the graying light, I made a last little climb up to the dirt road (East Blue Ridge recreation road) to the northern terminus of the North Backbone Trail.

I scurried up the slope behind the road, following a scratch trail that led to the PCT. Turning left (west) and continuing at a pretty fast clip, I arrived at a spot just to the west of the large slide above Wrightwood. The lights of homes were now twinkling in the early evening darkness. Time to get the flashlight out. I continued on in the dark, amongst and under the tall white fir and pines. Still no one around. Perfect. Here and there you could make out the silhouette of Pine Mountain to the south. A short time later was the turn-off for the Acorn Trail, which would descend about 1,600′ feet down into upper Wrightwood. Up here, it was possible to reach Joanie by radio, and yes, you guessed it…. Without a bit of shame, I took the ride back to our home in the little red Honda while Joanie told me about her day. Why the hell not? Who wants to walk on pavement I say to myself. That ride was heaven on earth. And so there you have it, it’s possible to walk across the highest point in the San Gabriels in a day! The next day my thighs felt entirely spent while walking on the little stone paths around our yard. And yet, looking back on it all, such as all good hikes, it was definitely worth it.