The Greatest Horse Thief

Chief Walkara (also spelled Wakara or Walker) was a Ute leader who rose to prominence during the early 1800s in what is now Utah, Nevada, and parts of California. Born around 1808 near the Spanish Fork River, he belonged to the Timpanogos band of the Ute people. He was one of several brothers who became influential chiefs, including Arapeen and Sanpitch. From an early age, Walkara was known for his mastery of horses, his courage in battle, and his sharp understanding of trade and diplomacy. These traits positioned him to take full advantage of the chaotic frontier world between Native peoples, Mexicans, and Americans along the Old Spanish Trail.

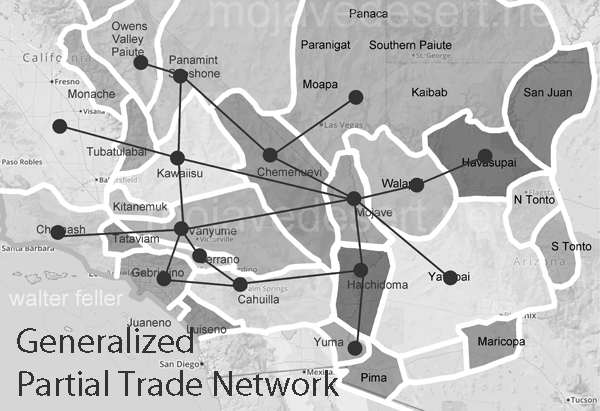

Walkara’s early fame came from his raiding and trading operations along the Old Spanish Trail, the overland route linking Santa Fe and Los Angeles. During the 1820s and 1830s, this route passed through Ute country, and Walkara quickly learned that power came from controlling who moved through it. He and his men imposed tolls on Mexican traders, demanding gifts of blankets, powder, or metal goods in exchange for safe passage. These tolls were enforced by threat of force but usually honored by both sides, as the traders knew they could not travel safely without Ute permission. Over time, Walkara’s camp became a trading post in its own right, where goods from New Mexico and California were exchanged for furs, horses, and captives.

His influence grew through large-scale raiding, particularly horse raids on ranches and missions in southern California. Walkara’s bands, sometimes numbering 100 to 200 mounted warriors, crossed the Mojave Desert to raid the ranchos of San Luis Obispo, San Juan Capistrano, and Mission San Gabriel. One raid in 1840 reportedly netted as many as 3,000 horses and mules, all of which were driven back across the desert without a single man being lost. His skill in organizing and leading these raids earned him the nickname “the greatest horse thief in the West.” The horses were driven north and east to Utah, where they were traded to Mexican or American intermediaries for guns, powder, and whiskey. Among those traders were mountain men such as James Beckwourth and Thomas “Pegleg” Smith, who became Walkara’s partners. They supplied him with weapons and other goods and, in turn, took the stolen horses to market in Santa Fe or Oregon, often reaping huge profits.

Walkara’s power extended beyond raiding. He also commanded loyalty and fear among many Great Basin tribes. Some allied with him for protection or shared in his profits; others paid tribute to avoid attack. He often incorporated Paiute, Goshute, and Shoshone warriors into his raiding parties. His leadership and wealth gave him the stature of a regional warlord, and even his enemies respected his authority. By the 1830s, he was widely recognized by traders from both Mexico and the United States as the most powerful Ute chief in the Great Basin.

A darker side of Walkara’s trade network was his involvement in the Native slave trade. The Utes had long been active in capturing people from neighboring tribes, particularly the more vulnerable Paiutes and Goshutes, and selling them to New Mexican traders. Walkara expanded this practice into a large-scale system of slave raiding. His men attacked Paiute and Goshute camps, taking women and children captive to sell or trade. Many of these captives were sold to Hispanic traders from New Mexico, who took them south to be used as domestic servants, laborers, or farmhands. Children were preferred because they were easier to train and control, and young girls were especially valued. Prices were often recorded as approximately $200 for a girl and $150 for a boy. This trade devastated the Paiute and Goshute peoples, forcing them to live in hiding and even to sell their own children in times of famine to avoid starvation. Horses and captives were often traded interchangeably—one could be exchanged for the other—creating a grim but efficient cycle of commerce that enriched Walkara’s band.

Walkara’s involvement in this trade was no secret. Mexican records show that New Mexican traders, including men such as Don Pedro León Luján, met with Walkara and other Ute chiefs to trade for captives in the 1830s and 1840s. Although Mexican law forbade the practice, it was widely tolerated in frontier regions. When American settlers and Mormon pioneers began arriving later, they were shocked by the existence of this trade. However, many of them also purchased captives as servants under the justification of “redeeming” them. Among the Utes themselves, some oral traditions dispute that Walkara directly sold captives, suggesting that later historians exaggerated the practice or misunderstood Ute customs. Even so, contemporary reports from Mexican, American, and Mormon sources confirm that his band played a significant role in supplying the slave markets of New Mexico.

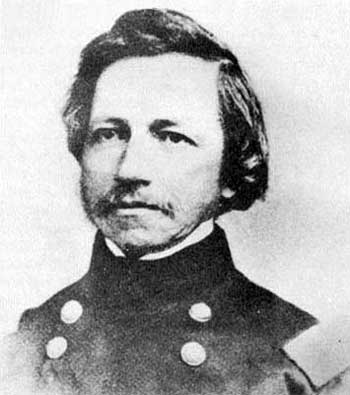

During these same years, Walkara cultivated relationships with both Mexican and American traders. His dealings with Mexican traders were essentially pragmatic—he provided horses and slaves in exchange for guns, ammunition, knives, and whiskey. With American trappers and explorers, his relations were usually friendly and based on mutual trade. The Utes found that trading with Americans brought better goods than the old Spanish system had, and Walkara’s fluency in both Spanish and English helped him act as a go-between. He often guided traders through Ute territory or arranged safe passage for them in exchange for gifts and favors. American mountain men respected him as a man of intelligence and courage. When John C. Fremont’s expeditions passed near Ute lands in the early 1840s, they noted the presence of influential Ute leaders who controlled the trade and movement in central Utah—almost certainly referring to Walkara.

By the time the first Mormon settlers entered the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, Walkara was already a well-known figure across the entire Great Basin. He had grown wealthy in horses, arms, and trade goods, and his name was known as far as Santa Fe and Los Angeles. Initially, he welcomed the Mormon pioneers, hoping they would become valuable trading partners like the trappers before them. He even accepted baptism into the Mormon Church in 1850, though this was likely more a political gesture than a religious conversion. However, as the Mormons expanded their settlements, they began to interfere with the horse and slave trades that had been central to Walkara’s power. These changes, combined with growing tensions over resources, eventually led to the Walker War of 1853–1854. But in his earlier years, long before that conflict, Walkara was already a legend—an adaptable and ambitious leader who built an empire of horses, trade, and influence stretching from the Mojave Desert to the Rocky Mountains.

He died in 1855 near Meadow, Utah, reportedly from pneumonia, and was buried according to Ute custom with his horse and belongings. His life marked the end of an era when Ute power and frontier trade shaped the fate of the Great Basin, before the arrival of settlers and soldiers transformed it forever.