mojavedesert.Net/railroads

Railfanning refers to the hobby or activity of watching, photographing, and sometimes documenting trains and railroads. Railfans, or rail enthusiasts, engage in railfanning for various reasons, including a fascination with trains, locomotives, and rail infrastructure, as well as an interest in the history and operations of railroads.

Railfanning activities can include:

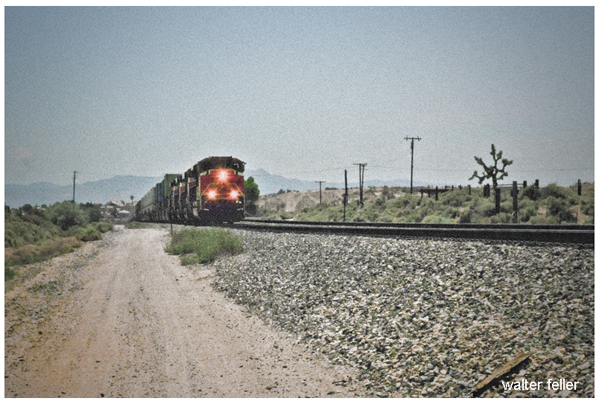

- Spotting Trains: Railfans often visit train stations, rail yards, and scenic locations along rail lines to observe and photograph trains as they pass by.

- Photography and Videography: Railfans use cameras and video equipment to capture images and footage of trains. Some focus on capturing the unique designs of locomotives, while others may document rare or historic trains.

- Collecting Memorabilia: Railfans often collect items related to trains, such as timetables, tickets, and other memorabilia. Some may also collect model trains.

- Tracking Train Movements: With modern technology, railfans can use websites, apps, and radio scanners to track the movements of trains in real time. This allows them to plan their railfanning activities and capture specific trains.

- Engaging in Online Communities: Many railfans connect through online forums, social media groups, and websites dedicated to railfanning. They share their experiences, photos, and information about train sightings.

- Visiting Railroad Museums: Railfans may also enjoy visiting museums dedicated to preserving and showcasing the history of railroads. These museums often have static displays of historic locomotives and rolling stock.

- Documenting Railroad History: Some railfans are also historians who document the history of railroads in their region. They may research and compile information about past and present rail lines, companies, and infrastructure.

Railfanning is a diverse hobby with enthusiasts of all ages. The appeal of trains and railroads can range from an appreciation of engineering and technology to a nostalgic connection with the past. It’s a hobby that allows individuals to combine their love of transportation, history, and photography while enjoying the sights and sounds of trains in action.