Tonopah was one of Southern Nevada’s most prosperous mining communities, drawing hundreds of prospectors from its founding in 1900. Silver was first discovered on May 19, 1900, by prospector Jim Butler who was traveling through the area. On an overnight stop, Butler discovered silver outcroppings near Tonopah Springs. When Butler’s friend Tasker Oddie (later Nevada Senator and Governor) had Butler’s sample assayed, it was found to be worth $50-$600 per ton. That August, Butler and his wife staked eight claims in Tonopah. Mrs. Butler christened the first three claims Desert Queen, Burro, and Mizpah. The Mizpah became Tonopah’s largest producer over the next forty years. Later that year, Butler leased his claims for one year, collecting 25% of the royalties from the gold and silver ore that was mined.

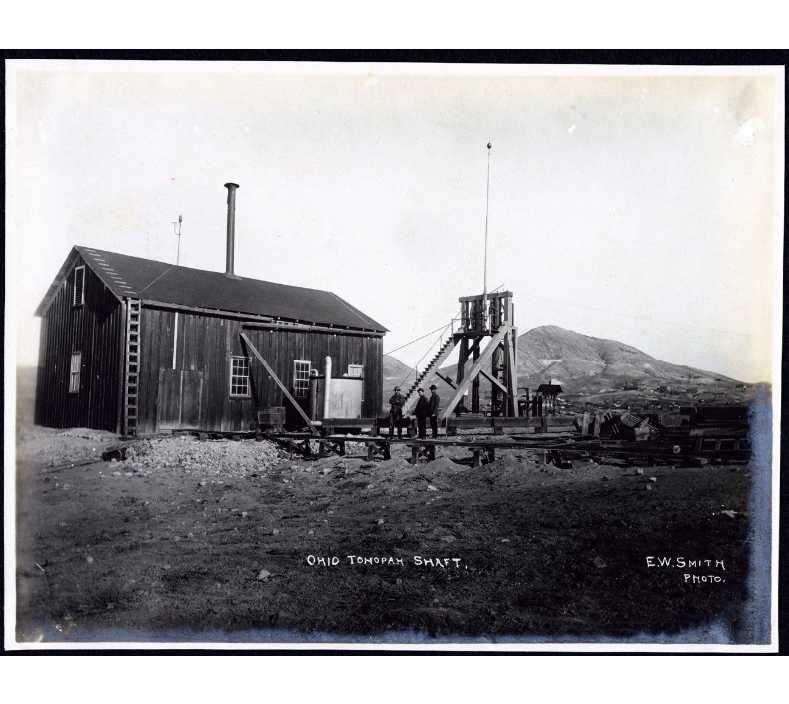

In 1901 several companies opened, including the West End Consolidated Mining Company and the Tonopah Extension Mining Company. In January, the mining camp had a population of 40, including three women. By springtime, the population rose to 250, and Tonopah’s first stage, the Concord, arrived from Sodaville. In May 1901, Tonopah’s first post office and the largest building in the city, The Mizpah Bar & Grill, opened. That summer, Tonopah’s population reached 650. W.W. Booth advertised the district through his newspaper, the Tonopah Bonanza. As word spread, more prospectors entered the area, and three large mining corporations were formed in early 1902: The Tonopah Belmont Mining Company, the Montana Tonopah Mining Company, and the Tonopah Mining Company.

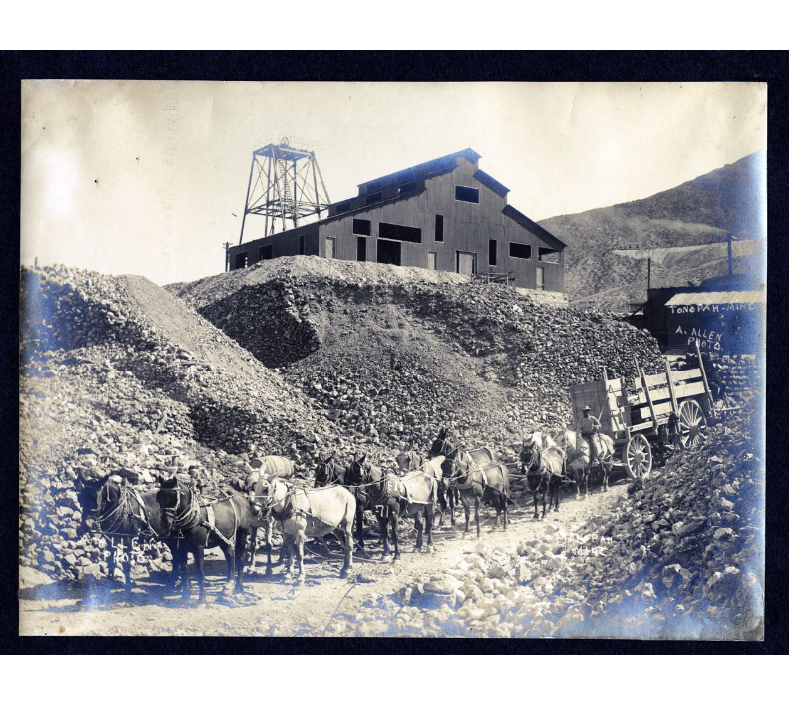

The camp was still relatively primitive in 1902. Prices, crude sanitary conditions, and Tonopah’s isolation made it difficult to obtain supplies. This changed in early 1903 when construction began on a 60-mile-long narrow gauge railroad connecting Tonopah with the Carson and Colorado Branches of the Southern Pacific Railroad at the Sodaville Junction.

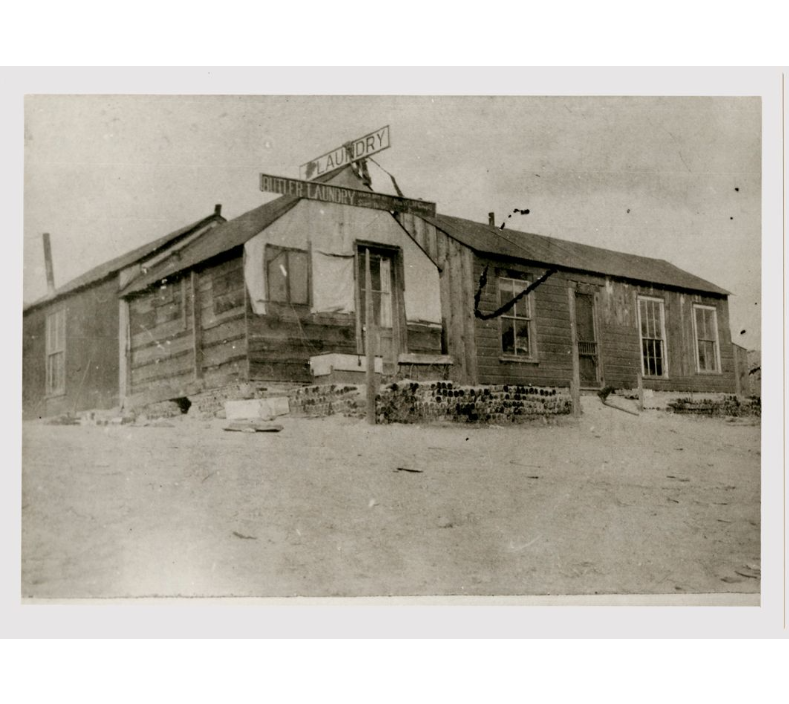

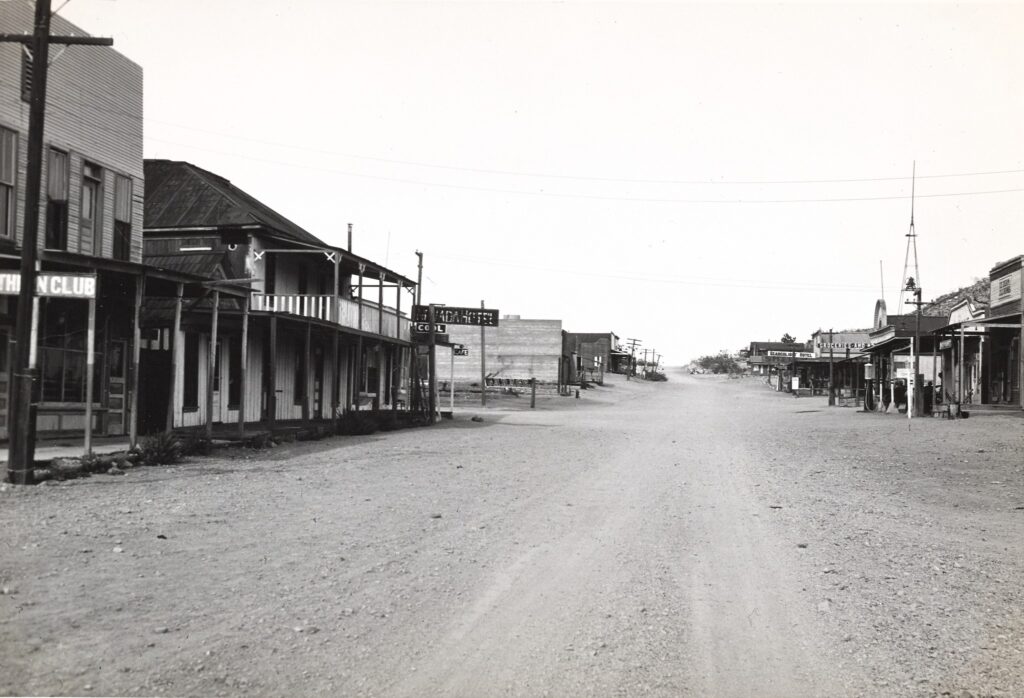

By the end of 1903, Tonopah’s population surged to 3,000. With several profitable silver and gold strikes, production boomed, and mining stocks listed on the San Francisco stock exchange since April soared. A building boom followed the mining boom. There were thirty-two saloons, six faro games, two dancehalls, two weekly newspapers, several mercantile stores, and two churches built before 1904. On July 25, 1904, the town celebrated the completion of the narrow gauge railroad with speeches, sporting events, horse races down Main Street, and several dances.

The population continued to grow as transportation to the district became easier, and by May 1905, the Nye County seat was moved from Belmont to Tonopah, the post office changed its name to Tonopah, and construction began on a new $55,000 Nye County courthouse. On July 7, 1905, Tonopah’s first city government was incorporated. In the fall, the two railroads in Tonopah merged into the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad Company, its track gauge standardized and extended to Goldfield.

Tonopah survived the financial panic of 1907. The city had five banks, modern hotels, cafes, an opera house, a school, electric and water companies, numerous gambling halls, and several four to five-story buildings downtown. In 1908 and 1909, Tonopah was devastated by a series of fires. In May 1908, a fire destroyed an entire block of the commercial district. A year later, the roundhouse and the machine shops at the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad burned to the ground. The infamous Belmont fire occurred on February 23, 1911, when the 1,200-foot mine shaft of the Belmont Mine caught fire. Seventeen men perished from the toxic fumes of the blaze.

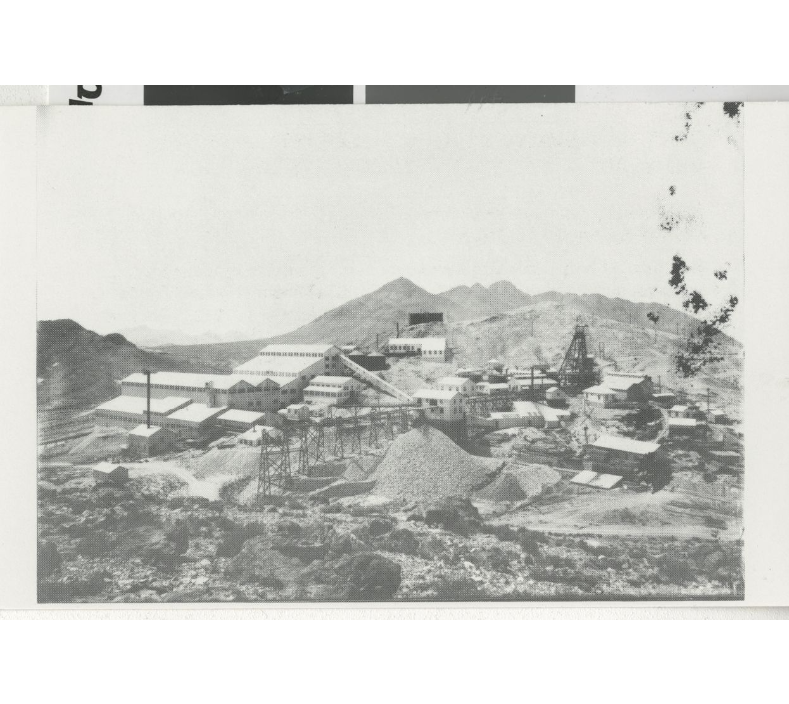

Mining activity expanded in 1912 when the Belmont mine and mill began operating in July. The daily wage for a machine operator averaged $4.50-$5.50 per shift. The following year was Tonopah’s most profitable: Annual production in gold, silver, copper, and lead was valued at $10 million. Several mills were constructed to process 1,830 tons of ore daily, including the Tonopah Belmont Development Company’s massive 500-ton mill on the east side of Mount Oddie.

Tonopah reached its peak production between 1910 and 1914. Between the end of World War I and the Great Depression, four companies remained active: the Tonopah Mining Company, Tonopah Belmont, Tonopah Extension, and West End Consolidated Mines. In 1921, four of the twenty-five principal silver mines in the nation were still in Tonopah, and Tonopah was the nation’s second-largest producer of gold. But on October 31, 1939, a fire destroyed the Belmont Mine, and another fire in 1942 closed the Tonopah Extension Mill. World War II brought an Army Air Force Base to the area, but it was shut down upon the close of the war. When the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad ceased operations in 1947, Tonopah’s remaining mines closed, and the population dwindled.

The total production of Tonopah’s mines over its forty years of production is estimated at over $150 million, and during that time, Tonopah produced many millionaires and statesmen, including Tasker Oddie, Jim Butler, Frank Golden, Zeb Kendall, and Key Pittman. In the words of Nevada historian Stanley Paher, “Virginia City had put Nevada on the map; Tonopah kept it there.”

Tonopah, Nevada

https://special.library.unlv.edu/boomtown/counties/nye.php#tonopah