by Alice Hall

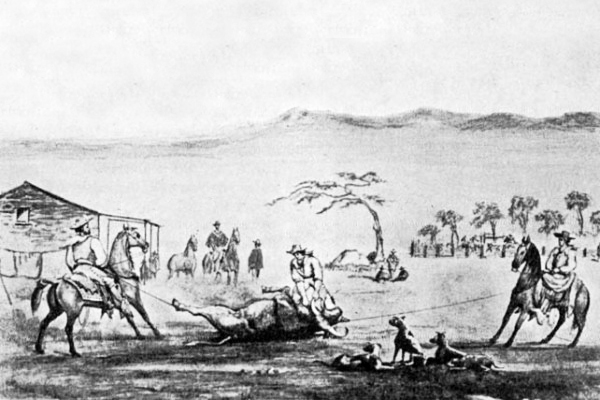

When our family moved to Devore in 1948, Glen Helen was home to Doc and Belle Davis, but in 1952 it became a County working farm growing all kinds of crops, from potatoes to asparagus. Hereford and Angus cattle ranged on many acres of pasture, and 50 acres were planted to alfalfa. Horses were used to round up and rope cattle.

Prisoners that did the farm work were trucked in from the Chino Men’s Prison, and the farm overseer was Tony Gianinni. Two of his three children, Carl and Paula, became our playmates.

According to Carl (Gianinni) Durling, Glen Helen Farm consisted of about 1,300 sprinkler-irrigated acres out of 2000, some 800 acres dry farmed, and leased grazing land brought the total to 4,000 acres of useable land.

BEFORE MY DAY

Early records call the place Glen Hellen. One of the “l”s was dropped from Hellen between 1888 and 1900. Many rumors exist about the origin of the name, but there is no official reason for the name Glen Helen.

George and Sarah Martin were listed in the 1870 census as owning 2,700 acres of land at the lower end of Cajon Pass worth about $10,000. They had purchased it in 1864 when it was on the delinquent tax list. Mrs. Foote and Jesse Martin were also associated with Glen Helen.

They shared their abode with military men, private citizens, and newspaper reporters, among others who traveled through. During the Civil War, a Union Post under the command of Col. William Hoffman, called Camp Cajon, was located at Martin’s Ranch.

Reportedly, up to 2,360 acres of the Muscupiabe Rancho went directly to the Martins. Names of Hancock and Wilson and Muscoy Water Company have also been associated with the property. And John and Nettie Cole co-owned part of it with Wilson in the late 1800s for a Jersey breeding farm.

When George Martin died in 1874, his oldest son, Archibald, started selling the Martin property. However, the name Martin’s Ranch clung to the property through several other owners. One of those owners apparently threw some lavish parties that were attended by people from town, as well as county residents.

Another son of George and Sarah, Samuel Martin, built his home at the foot of the Mojave Trail near Cable Canyon in 1873. A third son, George, is also listed in the 1887 County Directory as living in the “Martin’s District,” which covered lower Cajon Pass, the Devore area, and the Verdemont area. In 1882, Samuel Martin sold 300 acres to Julius Meyer, who developed much of Verdemont.

In the early 1900s, the Terribilini brothers ran a dairy on Glen Helen, and then the property passed into the hands of the Muscoy Water Company. John Terribilini married Lily Bubier, whose family also lived in that area, and moved up the dirt road, now paved and called Glen Helen Road.

In 1926 the Muscoy Water Co. sold its Glen Helen holdings to Jonas and Roof, who formed the Muscoy Syndicate. By 1930 the Syndicate owned 5640 acres of irrigable land with only 3000 irrigated. G.S. Towne bought back the Muscoy Water Company in 1936, and in 1948 the Muscoy Water Co. sold 2,079 acres of Glen Helen to San Bernardino County. Its extensive water ditch had not been used in years, the whole plan having been destroyed by the flood of 1938.

During this time, Doc and Belle Davis lived at Glen Helen until the county decided to start its farm. Also, Gene and Liz Grogan and their children Susan and Nick lived there in 1969-70 because Billy and Thelma Beardsley had moved their horse training stables to Glen Helen, and Liz worked for them. Thelma was also the music director for County Schools. After Glen Helen became a park, the Grogans moved onto Cajon Blvd., where Liz, a vocal county government watchdog, could keep her horses.

Look for more on Glen Helen!

Photo 1—A view of Martin’s Ranch circa 1870, later Glen Helen. Photo found in the San Bernardino County Archives.

Photo 2—Tony Gianinni and his children check the Glen Helen reservoir in the early 1950s. Photo sent via e-mail by Carl Gianinni Durling.

Photo 3—The Glen Helen barn housed the cattle and horses in 1952. Photo via e-mail from Carl (Gianinni) Durling.