Summit Valley: A Historical Overview

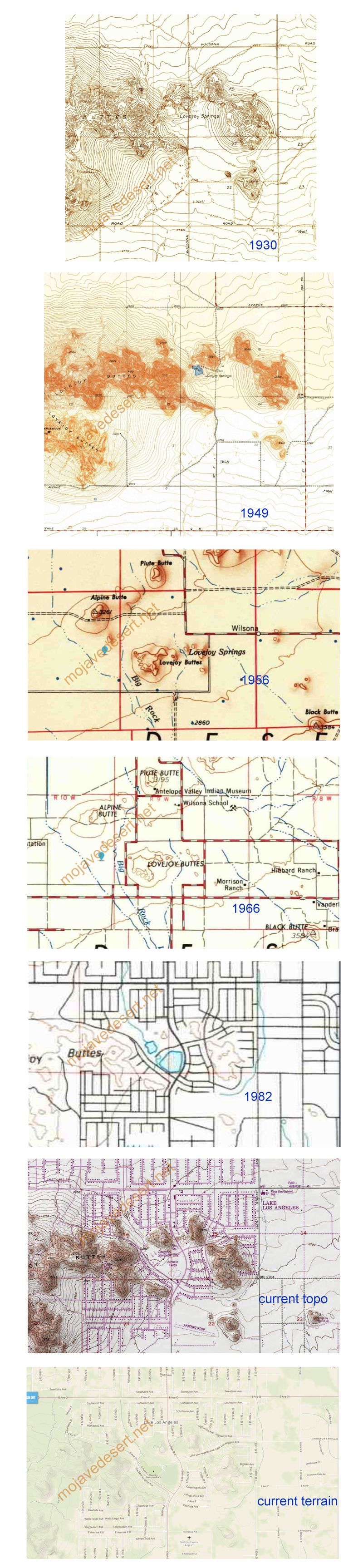

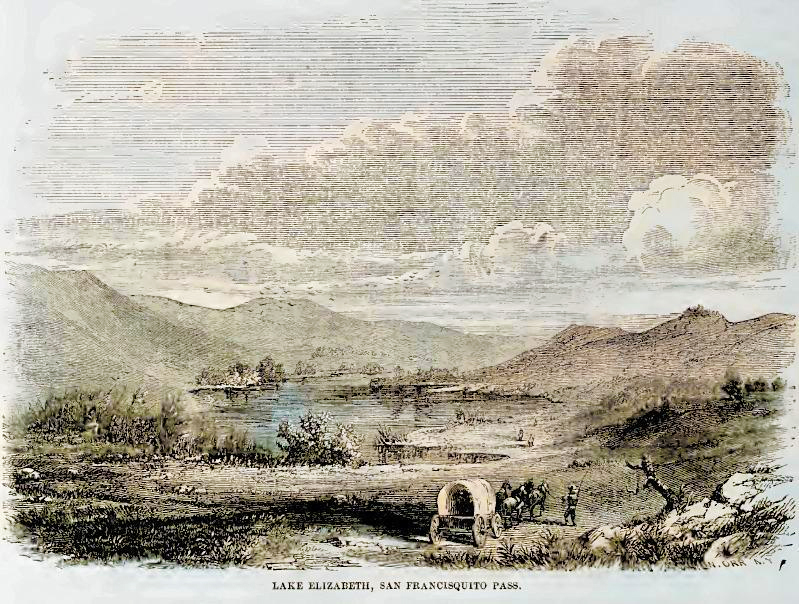

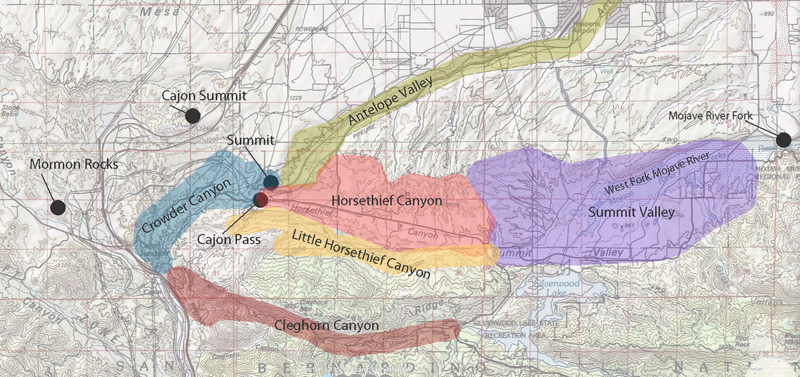

Summit Valley is a region rich in history and natural beauty in Southern California. Nestled between the Mojave Desert and the Southern California Mountains, it lies east of the Cajon Pass. Hesperia borders it to the north and the San Bernardino National Forest to the south. This valley, traversed by the West Fork of the Mojave River, holds significant historical and ecological importance.

Key Historical Figures and Events

1776: Fr. Francisco Garcés

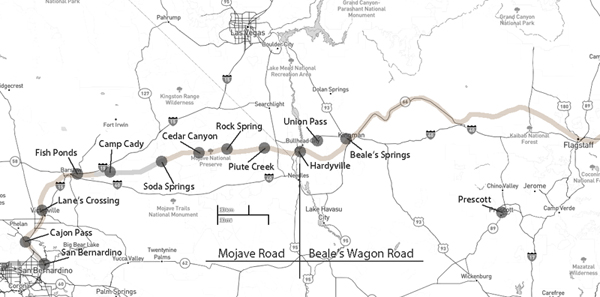

Francisco Garcés, a Spanish Franciscan missionary and explorer, traveled through Summit Valley in 1776 as part of his extensive travels across the American Southwest. Garcés played a crucial role in establishing early routes and missions in the region, and his detailed diaries provide valuable insights into the landscape and indigenous peoples.

1826: Jedediah Smith

Jedediah Smith, a renowned American frontiersman, trapper, and explorer, led an expedition through Summit Valley in 1826. This marked one of the earliest American explorations of the region, significantly contributing to the mapping and understanding of the Western United States.

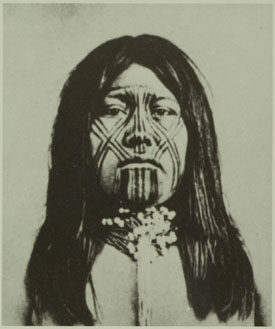

1840: Chaguanoso Raid

The Chaguanoso raid was the largest stock theft in California’s history. On May 14, 1840, Juan Perez, the administrator of Mission San Gabriel, reported the theft of mares by Chaguanoso raiders. Tiburcio Tapia, a prominent Californian businessman and alcalde of Los Angeles, directed the pursuit of the robbers who crossed the Mojave Desert. Despite the efforts of men like Ygnacio Palomares and José Antonio Carrillo, the raiders largely escaped.

Early 1840s: Michael White (Miguel Blanco)

In the early 1840s, Michael White (Miguel Blanco) confronted horse thieves led by Chief Coyote in Crowder Canyon. White’s successful defense of his cattle, culminating in the killing of Chief Coyote, marked a significant moment in the region’s history and highlighted the persistent threat of banditry.

Settlement and Development

1866: Summit Valley Massacre

On March 25, 1866, Edwin Parrish, Nephi Bemis, and Pratt Whiteside, young cowboys employed at Las Flores Ranch, were ambushed and killed by Piute Indians near Las Flores Ranch. This violent episode highlighted the ongoing tensions between settlers and native populations.

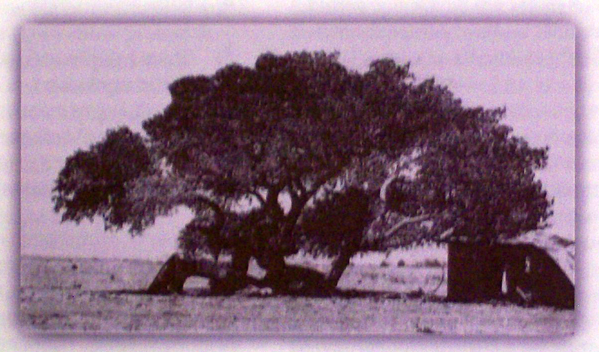

Late 1800s: Las Flores Ranch

In the late 1800s, cattle driven from Arizona were pastured on Summit Valley’s green grass and running water and fattened before being sent to market in San Bernardino. Despite the challenges from wildlife and hostile natives, the ranch became central to the regional economy.

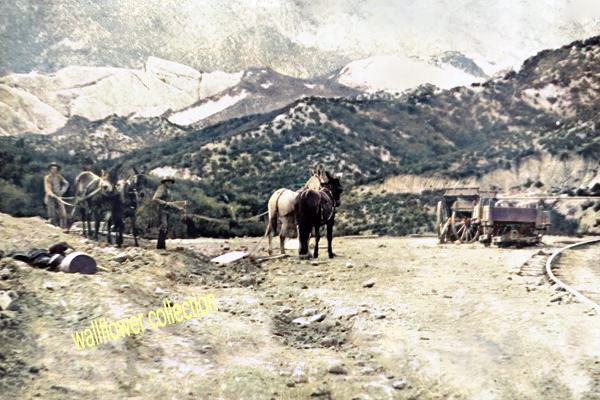

1884-1885: Railroad Construction

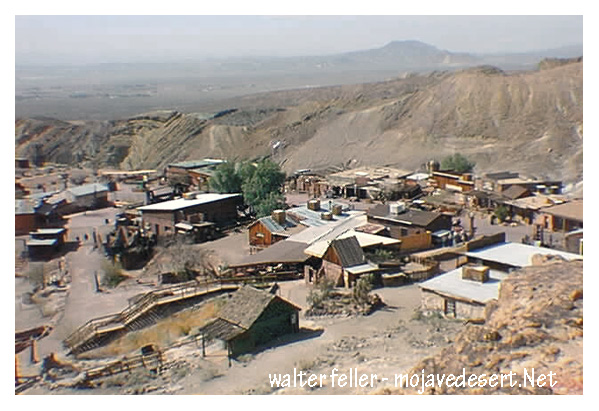

The construction of the Southern California Railroad in 1884-1885, following the old Spanish Trail route, was a significant development. Summit, located about six miles west of the Bircham Ranch, became a crucial station for shipping supplies. Despite unsuccessful oil explorations, the area continued to develop.

Early 1900s: Agricultural Growth

Summit Valley’s fertile lands and plentiful water made it an attractive location for cattle ranching. Early settlers capitalized on these resources, establishing large ranches that became central to the valley’s economy. Over time, the introduction of railroads and improved transportation infrastructure facilitated the growth of agriculture and livestock trade, further cementing the valley’s role as a key agricultural hub.

1924: Modern Infrastructure

By the early 20th century, the region had developed a network of roads and railroads, with State Route 138 emerging as a critical transportation corridor. This infrastructure supported the valley’s continued growth and integration into the broader Southern California economy while preserving its historical legacy and natural beauty.

Ecological and Recreational Importance

Biodiversity and Conservation

Summit Valley has diverse habitats, from montane forests and riparian zones to grasslands and desert ecosystems. These habitats support a variety of wildlife, including many species of birds, mammals, and plants. Conservation efforts in the valley focus on protecting these natural resources, managing invasive species, and ensuring the region’s ecological health.

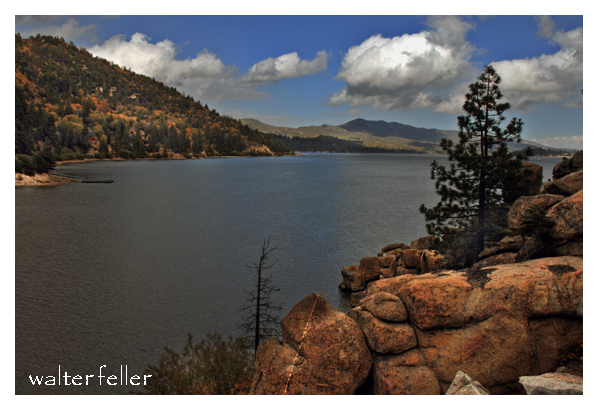

Silverwood Lake and Recreational Activities

The creation of Silverwood Lake as part of the California State Water Project has significantly enhanced the recreational opportunities in Summit Valley. The lake offers boating, fishing, hiking, and camping activities, attracting regional visitors. The Pacific Crest Trail, which passes through the valley, provides additional opportunities for outdoor enthusiasts to explore the area’s natural beauty.

Cedar Springs, CA

Cedar Springs was a small community in the San Bernardino Mountains, submerged by the creation of Silverwood Lake in 1971. Before the lake’s construction, Cedar Springs was known for its natural beauty, with lush cedar forests and clear springs that attracted visitors and residents alike. While the community was lost, the lake’s creation transformed the area into a major recreational destination.

Conclusion

Summit Valley’s rich history, from early exploration by figures like Francisco Garcés and Jedediah Smith to significant events like the Chaguanoso raid and Summit Valley massacre, paints a vivid picture of a region that has played a crucial role in Southern California’s story. From the challenges faced by early settlers to its modern-day significance as a recreational and ecological haven, Summit Valley remains a testament to the dynamic interplay between human activity and the natural world.