In the lonely reaches of the El Paso Mountains, where the desert stretches wide and the wind whispers through the canyons, Dutch Charley—better known as Charles Koehn—built a life that was equal parts rugged and legendary. A German immigrant turned desert rat, Koehn made his mark not with gold, but with grit, ingenuity, and a bit of old-fashioned stubbornness.

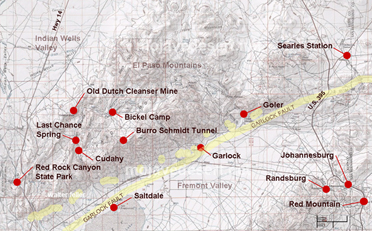

Koehn’s story begins in the 1890s, when he staked a claim at Kane Springs, a much-needed watering hole along the route between Tehachapi and the Panamint Range. While many men chased dreams of striking it rich in the goldfields, Dutch Charley had a different plan—he set up shop right in the heart of the action, offering supplies, water, and even a mail service to the miners and drifters passing through. For 25 cents a letter, a prospector could send word back home, and for a few more coins, he could rest his bones and share a drink at Koehn’s outpost. It wasn’t just a business; it was a lifeline in an unforgiving land.

Despite his knack for trade, Koehn had a prospector’s heart. He spent years scouring the desert for something valuable, and while he never found the gold mother lode, he did uncover something else—gypsum. In 1909, he staked claims on a massive gypsite deposit near his homestead, and by 1910, he had a small operation producing wall plaster. It wasn’t the romantic vision of striking it rich, but it was a steady business. His holdings expanded over the years, and soon, larger companies were leasing his land to extract the valuable mineral.

But life in the Mojave wasn’t just about hard work—it was also about holding your ground. In 1912, a group of claim jumpers, backed by hired guns, tried to push Koehn off his land. The desert was a lawless place, and disputes like these were often settled with more than just words. Koehn, known for being tough as nails, didn’t back down. A gunfight erupted on the dry lakebed, and when the dust settled, Dutch Charley was still standing. The courts later ruled in his favor, affirming his rights to the land. It was the kind of incident that turned a man into a legend.

For decades, Koehn’s outpost—known as Dutch Charley’s Cabin—served as a beacon for desert wanderers. Whether it was a weary prospector looking for water, a film crew from Hollywood needing a mule team, or just a lost traveler in need of a friendly face, Koehn’s place was a welcome sight in the vast emptiness. His generosity was well known, and many recalled his habit of offering water to anyone who needed it, free of charge. It wasn’t just about business—it was about survival, about knowing that out here, in the middle of nowhere, a little kindness went a long way.

But time and fortune have a way of shifting like the desert sands. In the 1920s, Koehn found himself in a series of legal battles over his gypsum claims, and in 1923, he was arrested for allegedly attempting to bomb the home of a judge involved in one of his disputes. Whether he was guilty or the victim of a setup is still debated, but the outcome was clear—he was convicted and sent to San Quentin State Prison. It was a tragic end for a man who had spent his life fighting to carve out a piece of the desert for himself. He died behind bars in 1938, just days before he was scheduled to be released.

Though Koehn himself is long gone, his legacy remains. Koehn Dry Lake still bears his name, a reminder of the claim fights and salt works that once played out on its barren surface. The remains of Dutch Charley’s Cabin stand as a ghostly relic of a bygone era, a time when men built lives in the harshest of places with nothing but their hands, their wits, and an unbreakable will. His story, filled with hardship, adventure, and the occasional brush with the law, is woven into the fabric of Mojave history.

Dutch Charley was more than just a miner or a businessman. He was a character, a survivor, and above all, a man who belonged to the desert. He may not have left behind great wealth, but he left something just as enduring—the kind of story that echoes through the canyons long after the last prospector has gone.