A natural thread of wildlife presence woven in, showing how desert creatures went about their lives while miners, homesteaders, and road-trippers came and went:

Ivanpah Valley: Mining, Settlement, and the Story of the Mojave

Nestled in the northeastern part of San Bernardino County, the Ivanpah Valley tells a story of shifting sands, silver dreams, and the rugged endurance of those who dared to live in one of the harshest corners of the American West. This desert basin, with its sweeping alluvial fans and ancient hills, bears the marks of both geologic forces and human ambition. From the first mining camps to homesteaders and the rise of Route 66, Ivanpah is a quiet but enduring witness to the broader saga of the Mojave Desert, a place of allure and mystery that has captivated generations.

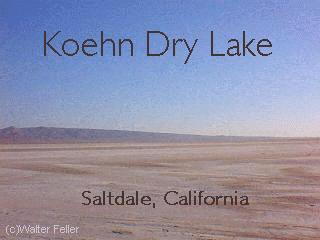

The valley lies 2,600 and 4,500 feet above sea level and is part of Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 30g. Its surface comprises fluvial, lacustrine, and wind-blown sands laid down during the Quaternary period, while occasional outcrops of rugged Precambrian rock poke through the sediment. Gently sloping alluvial fans define the terrain, while basin floors and dry lake beds, known as playas, stretch toward the horizon. Rain is rare—only about 4 to 7 inches fall yearly—yet the soil and climate support hardy desert plant communities like creosote bush, Joshua tree, saltbush, and greasewood, depending on moisture and soil type.

Amidst all this change and activity, the local wildlife continued its existence with a quiet resilience. Wagons rattled over gravel trails, and miners pounded away at rock walls. Yet, desert tortoises quietly roamed the flats, burrowing down into the cool earth to escape the heat. Coyotes trotted unseen along arroyos, pausing now and then to listen. Jackrabbits darted through greasewood and shadows, while red-tailed hawks circled high above the empty mining camps. For the creatures of the desert, life pulsed to an older rhythm, indifferent to boom or bust, a testament to the enduring resilience of the natural world.

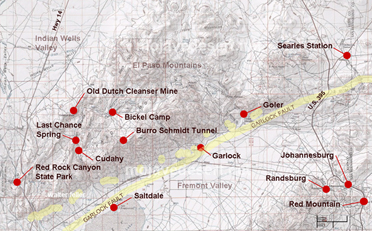

Into this arid but mineral-rich land came waves of miners in the 19th century, drawn by tales of hidden veins and easy fortunes. In 1860, the first productive mine in the Mojave—called “Christmas Gift”—opened in Death Valley, setting off a flurry of activity across the desert. Borax, known as “the white gold of the desert,” was soon discovered and began to be mined profitably. By the 1870s, the Clark Mountain Mining District was established, and with it the town of Ivanpah, at that time the only sizable American settlement in the eastern Mojave.

The Bullion Mine, located on the north end of the Ivanpah Mountains, began production in the 1860s. Its rich silver ore was shipped down the Colorado River and on to Swansea, Wales. In 1879, the mine was producing steadily—about five tons every three days—and wagons driven by Jesse Taylor hauled the ore out across the desert. That same year, the mine superintendent, James Boyd, made headlines by replacing an Indian laborer who earned 75 cents a day with a teenage boy, advertised in the San Bernardino Weekly Times, who would work for $30 a month and board–this was frontier economics at its most practical.

The mine changed hands over the years, and in 1909, it was leased by George Bergman of Eldorado Canyon, backed by a $50,000 bond. With multiple shafts and a depth of 250 feet, the Bullion Mine produced ore containing lead, copper, and silver into the 1910s but has seen no significant production since.

Other mines in the Ivanpah Mountains also flourished, if only briefly. The Standard Mine, discovered in 1904 on the west side of the range, operated from 1906 to 1910 and again during World War I. It was nearly 700,000 pounds of copper and 20,000 ounces of silver. By 1908, a small company town had sprung up around it, with bunkhouses, a store, and an assay office.

The Kewanee Mine, discovered around 1901, was especially busy between 1907 and 1911, employing fifty men and operating its mill.

The Morning Star Mine, just west of the Kewanee, saw its most active years between 1927 and 1939, and by the 1970s, it was still being worked in search of the estimated 100,000 ounces of gold beneath its claims.

A particularly curious chapter comes from the Kokoweef Caves, where, in the 1920s, a miner named E.P. Dorr claimed to have discovered an underground river of gold. The tale has since become the stuff of legend, with some continuing to search for treasure in the shadows of the Carbonate and New Trail copper mines nearby.

While miners chased fortune beneath the ground, another wave of settlers sought a different treasure—land. In 1910, homesteaders arrived under federal land programs, usually staking claims on 160-acre parcels. Many came to the Lanfair Valley and surrounding regions, hoping to make a go of desert farming. The rains of the early 1910s encouraged them—fields sprouted crops, and the dry air drew veterans of World War I suffering from the effects of mustard gas.

But the good years were short-lived. When the rains failed, wells dried up or never reached water. Homesteaders found themselves hauling water across miles of open land. Tensions over water rights flared between settlers and ranchers. Gradually, families gave up. They left behind lonely cabins, wind-worn and silent, scattered across the desert.

And still, the lizards sunned themselves on warm rocks. Desert bighorn sheep lined the mountain ridges, standing like statues in the morning light. After a lucky rain in the springtime, wildflowers painted the valley in yellow and purple while hummingbirds zipped among the blooms—untroubled by claims or county lines.

In the 1920s, the iconic Route 66 was born. Built to connect the Midwest to California, it followed old wagon trails and pioneer routes. It symbolized freedom and opportunity—nicknamed “The Mother Road” and “Main Street of America.” It inspired books, songs, and even a TV show. Its significance in shaping the American landscape and culture is undeniable, evoking a sense of nostalgia and appreciation in those who traverse its historic path.

Then came the Great Depression in the 1930s. Struggling families from the Dust Bowl followed Route 66 west, hoping to grow their food and escape the failing economy. After World War II, traffic along Route 66 surged. Though the road was narrow and dangerous in spots, it remained vital—until the 1950s, when new interstate highways like I-15 and I-40 began to bypass the small desert towns. The last section of Route 66 was officially decommissioned in 1985. But its memory lives on. Starting in 1995, “Historic Route 66” signs began appearing in all eight states the route once crossed. Today, travelers trace its path through the Mojave, chasing a piece of American history.

The Ivanpah Valley and its surroundings may seem quiet today, but the landscape still whispers the stories of boomtowns and busted dreams, sunburned miners and hopeful homesteaders, and dust-choked cars rolling west on Route 66. It is a land shaped by wind, stone, and determination—where people once came looking for gold and found, if not riches, a chapter in the great American tale. And through it all, the desert’s original residents—the coyotes, quail, snakes, and tortoises—have never left, carrying on as they always have, desert-born and desert-bound.