By Herman F. Mellen

In the beginning, Calico prided itself on being an anti-Chinese camp. But it proved almost impossible to get any but Chinese cooks, so anyone who maintained a mine boarding house or restaurant in the Calicos just about had to hire Chinese help.

Yung Hen-naturally called Young, started as a cook in the Snowbird mine in Mule Canyon. He was perhaps 50, though it was difficult to judge his age. In fact all of them – wore a long queue. And though they wore levis, they also wore their traditional Chinese blouses. I believe he was Cantonese.

After cooking at several mines, Yung Hen decided to go into business for himself by starting a restaurant in Calico. A mass meeting was held to prevent it at which a big Cornish miner arose and gave his solution to the problem: “I tell you, boys, if – we just keep the first one out we’ll never have any trouble with those that come afterward.”

The mass meeting didn’t stop Young Hen, nor did attempts to frighten .him away. Once a group took him out and actually had the rope around his neck, threatening to hang him if he did not leave. He said calmly, “All right, go ahead. Plenty more Chinamen where I come from.”

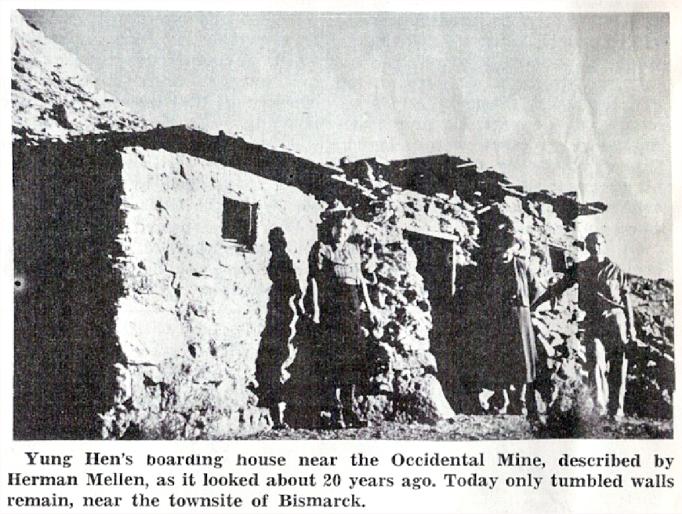

In time Yung Hen had three or four boarding houses. He spent most of his time in Calico, putting his cousins in the others as managers. In 1885 he bought out the family running the boarding house at the Occidental mine, where I was carpenter. I was loaned to him. He told me what he wanted done, building tables and benches, and moving partitions in adding another room to the building. Then he left me with his two cousins, who were I laughing and skylarking all day long.

One day these boys wanted me to eat with them. They had cooked a dish which they seemed to consider a great delicacy – with a foundation of dried abalones about the size and toughness of rubber boot heels and fully as black. After these had boiled a couple of hours, Chinese cabbage and some sort of small fish, both of which smelled to high heaven, were added and all were boiled another hour. Twenty minutes before serving, two-inch cubes of fat fresh pork were added and cooked just long enough to become nearly transparent. The boys insisted that the stew was velly nice, but I felt I must decline it.

A couple of days after Christmas 1884, a young Irishman known as Scotty, who had been celebrating by imbibing largely on “tarantula juice,” decided to complete the celebration with a turkey dinner. So he flied to Yung Hen’s Calico restaurant and ordered turkey and fixin’s. The two young Chinese boys – cousins or nephews of Yung Hen – set before him all their remaining turkey, largely, scraps and bones.

This so highly offended Scotty that he forgot the spirit of Christmas, threw the food at the boy who waited on him, upset the table, and began smashing dishes and furniture. The two Chinese boys grappled with him, trying to put him outside, and in the melee, Scotty lost one shoe, most of one pants leg, and his shirt.

To the glory of old Ireland, he was holding his own until one of the boys rushed into the kitchen, returning with a bucket of almostboiling water in one hand and a long-handled dipper in the other. A few dippers of water placed where they did the most good and the restaurant and whole camp were too small for friend Scotty. He made what the boys facetiously called a straight shirttail for the mine where he was employed and spent several days nursing various scalded places about his person, the while he cursed the Chinese people in general and the relatives of Yung Hen in particular.

He didn’t receive much sympathy, however, as by then Yung Hen stood well in the camp. A goodly number of prospectors had been grubstaked by him and many a man had eaten on credit with him until he could get a job.

And by that time they had a saying that though he might be a young hen in name he was some tough old rooster by nature.

Calico Print – Harry Oliver – Klaxo.Net