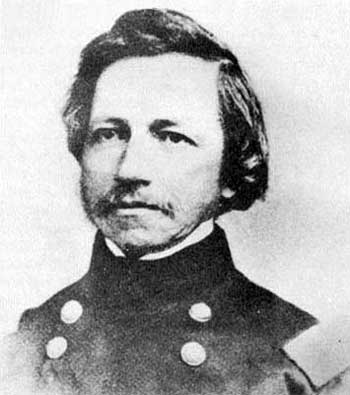

The Whipple 35th Parallel Railroad Survey, led by Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple in 1853, was a pivotal expedition to explore a potential transcontinental railroad route along the 35th parallel from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Los Angeles, California. Commissioned by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, the survey aimed to assess the feasibility of the railroad, gather scientific data, and document interactions with Native American tribes, significantly contributing to the understanding and development of the American West.

Excerpt from – Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

The Tribes of the Thirty-Fifth Parallel

September 1858

VOL. XVII.–No. 100

Mohaves

Leaving the beautiful valley of the Chemehuevis, we presently find our friends among the shrewd, sprightly, and hospitable Mojaves. On the 25th of February, they were honored by a visit of ceremony from a pompous old chief of the Mojaves, who presented credentials from Major Heintzelman.–The Major wrote that the bearer, Captain Francisco, had visited Fort Yuma, with a party of warriors, while on an expedition against the Cocopas, and that he had professed friendship; but Americans were advised not to trust him.

The parade and ceremony with which the visit was set off were not, in this instance, altogether vain and idle, for without them that august personage, Captain Francisco, might easily have been mistaken for the veriest[sic] beggar of his tribe. He was old, shriveled, ugly, and naked-but for a strip of dirty cloth suspended by a cord from his loins and an old black hat, band-less and torn, drawn down to his eyes. But his credentials were satisfactory, and he was received with all the honors and installed in a stately manner on a blanket. The object of the expedition was explained to him, and he cordially promised aid and comfort. A few trinkets, some tobacco, and red blankets cut into narrow strips were then presented for distribution among the warriors. The chief would accept nothing for himself, so the council was dissolved. The Mojave chiefs look upon foreign gifts in a national light and accept them only in the name of the people.

Savedra counted six hundred Indians in camp, of whom probably half had brought bags of meal or baskets of corn for sale. The market was opened, and all were crowding, eager to be the first at the stand, amidst shouts, laughter, and a confusion of tongues-English, Spanish, and Indian.

When the trading was concluded, the Mojave people sauntered about the camp in picturesque and merry groups, making the air ring with peals of laughter. Some of the young men selected a level spot, forty paces in length, for a play-ground, and amused themselves with their favorite game of hoop-and-poles. The hoop is six inches in diameter, and made of elastic cord; the poles are straight, and about fifteen feet in length. Rolling the hoop from one end of the course toward the other, two of the players chase it half-way, and at the same time throw their poles. He who succeeds in piercing the hoop wins the game.

Target-firing and archery were then practiced–the exploring party using rifles and Colt’s pistols, and the Indians shooting arrows.

The fire-arms were triumphant; and at last an old Mojave, mortified at the discomfiture of his people, ran in a pet and tore down the target. Notwithstanding the unity of language, the family resemblance, and amity between the Cuchans and Mojaves, a jealousy, similar to that observed among Pimas and Maricopas, continually disturbs their friendship. A squaw detected her little son in the act of concealing a trinket that he fancied. She snatched the bauble from him with a blow and a taunt, saying, “Oh, you Cuchan!” Some one inquired if he belonged to that tribe. “Oh no,” she replied ” he is a Mojave, but behaves like a Cuchan, whose trade is stealing !” Nevertheless, the Cuchans are welcomed by the Mojaves wherever they go.

These Indians are probably in as wild a state of nature as any tribe on American territory.

They have not had sufficient intercourse with any civilized people to acquire a knowledge of their language or their vices. It was said that no white party had ever before passed through their country without encountering hostility.

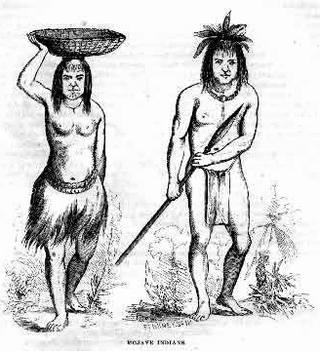

Nevertheless they appear intelligent, and to have naturally amiable dispositions. The men are tall, erect, and well-proportioned; their features inclined to European regularity; their eyes large, shaded by long lashes, and surrounded by circles of blue pigment, that add to their apparent size. The apron, or breech-cloth, for men, and a short petticoat, made of strips of the inner bark of cotton-wood, for women, are the only articles of dress deemed indispensable; but many of the females have long robes, or cloaks, of fur. The young girls wear heads.

When married, their chins are tattooed with vertical blue lines, and they wear a necklace with a single sea-shell in front, curiously wrought.

Those shells are very ancient, and esteemed of great value.

From time to time they rode into the camp, mounted on spirited horses; their bodies and limbs painted and oiled, so as to present the appearance of highly-polished mahogany. The dandies paint their faces perfectly black. Warriors add a streak of red across the forehead nose, and chin. Their ornaments consist of leathern bracelets, adorned with bright buttons, and worn on the left arm; a kind of tunic, made of buckskin fringe, hanging from the shoulders; beautiful eagles’ feathers, called “sormeh”–sometimes white, sometimes of a crimson tint-tied to a lock of hair, and floating from the top of the head; and, finally, strings of wampum, made of circular pieces of shell, with holes in the centre, by which they are strung, often to the length of several yards, and worn in coils about the neck.

These shell beads, which they call “pook,” are their substitute for money, and the wealth of an individual is estimated by the “pook” cash he possesses. Among the Cuchans, in 1852, a foot of “pook” was equal in value to a horse; and divisions to that amount are made by the insertion of blue stones, such as by Coronado and Alargon were called “turkoises,” [turquoise] and are now found among ancient Indian ruins.

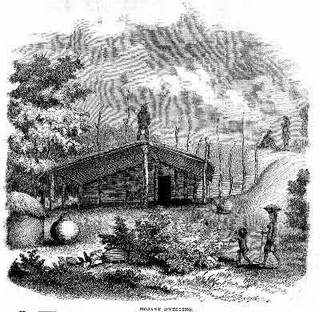

The Mojave rancherias are surrounded by granaries filled with corn, mesquite beans, and tortillas. The houses are constructed with an eye to durability and warmth. They are built upon sandy soil, and are thirty or forty feet square; the sides, about two feet thick, of wicker-work and straw; the roofs matched, covered with earth, and supported by a dozen cottonwood posts. Along the interior walls are ranged large earthen pots, filled with stores of corn, beans, and flour, for daily use. In front is a wide shed, a sort of piazza, nearly as large as the house itself. Here they find shelter from rain and sun. Within, around a small fire in the centre, they sleep. But their favorite resort seems to be the roof, where could usually be counted from twenty to thirty persons, all apparently at home. Near the houses were a great number of cylindrical structures, with conical roofs, quite skillfully made of osiers; these were the granaries, alluded to above, for their surplus stores of corn and mesquite.

As the explorers passed these rancherias, the women and children watched them from the house-tops; and the young men, for the moment, suspended their sport with hoop and poles. At first only a few of the villagers seemed inclined to follow them, but at length their little train swelled to an army a mile in length.

On the 27th of February, being favored with a clear and calm morning, they hastened to take advantage of it to cross the river; but the rapid current and the long ropes upset their ” gondola” in mid-stream. The Mojaves, who are capital swimmers, plunged in and helped them save their property. Many had brought rafts to the spot, anticipating the disaster. These were of simple construction, being merely bundles of rushes placed side by side, and securely bound together with osiers.

But they were light and manageable, and their crews plied them with considerable dexterity.

It was night when finally the great work was accomplished-the Colorado crossed, and the camp pitched on the right bank.

Our friends had now quite exhausted their stock in trade in gifts, although large quantities of grain were yet in camp for sale. When told that their white brothers were too poor to buy, the Indians expressed no disappointment, but strolled from fire to fire, laughing, joking, curious but not meddlesome, trying, with a notable faculty of imitation, to learn the white man’s language, and to teach their own.

As long as our explorers were among them, these Mojaves were gay and happy, talking vicariously, singing, laughing. Confiding in the good intentions and kindness of the strangers, they laid aside for the time their race’s studious reserve. Tawny forms glided from one camp-fire to another, or reclined around the blaze, their bright eyes and pearly teeth glistening with animation and delight. They displayed a new phase of Indian character, bestowing an insight into the domestic amusements which are probably popular at their own firesides: mingling among the soldiers and Mexicans, they engaged them in games and puzzles with strings, and some of their inventions in this line were quite curious.

No doubt these simple people were really pleased with the first dawning light of civilization.

They feel the want of comfortable clothing, and appreciate some of the advantages of trade. There is no doubt that, before many years pass away, a great change will have taken place in their country. The advancing tide of emigration will sweep over it, and, unless the strong arm of Government protects them, the Mojaves will be driven to the mountains or exterminated.

When the exploring party wore about to leave, the chiefs came with an interpreter, to say that a national council had been held, in which they had approved of the plan for opening a great road through the Mojave country. They knew that on the trail usually followed by the Pai’ Utes toward California the springs were scanty, and insufficient for the train; that thus the mules might perish on the road, and the expedition fail. Therefore they had selected a good man, who knew the country well, and would send him to guide their white brothers by another route, where an abundance of water and grass would be found. They wished their white brothers to report favorably of their conduct to the Great Chief at Washington, in order that he might send many more of his people to pass that way, and bring clothing and utensils to exchange for the produce of their fields.

Desiring to learn something of their notions regarding the Deity, death, and a future existence, Lieutenant Whipple led an intelligent Mojave to speak upon these subjects. One stooped and drew in the sand a circle, which he said was to represent the former casa, or dwelling-place of Mat-e-vil, Creator of Earth (which was a woman) and Heaven. After speaking for some time with impressive, and yet almost unintelligible, earnestness regarding the traditions of that bright era of their race which all Indians delight in calling to remembrance, he referred again to the circle, and suiting the action to the word, added:

“This grand habitation was destroyed, the nations were dispersed, and Mat-e-vil took his departure, going eastward over the great waters. 110 promised, however, to return to his people and dwell with them forever; and the time of his coming they believe to be near at hand.”

The narrator then became enthusiastic in the anticipation of that event, which is expected to realize the Indian’s hopes of a paradise on earth. Much that he said was incomprehensible. The principal idea suggested was the identity of their Deliverer, coming from the east, with the Montezuma of the Pueblo Indians, or perhaps the Messiah of Israel; and yet the name of Montezuma seemed utterly unknown to this Indian guide. His ideas of a future existence appeared somewhat vague and undefined. The Mojaves, he said, were accustomed to burn the bodies of the dead; but they believe that an undying soul arises from the ashes of the deceased, and takes its flight, over the mountains and waters, eastward to the happy spirit-land.

Loroux says, that he has been told by a priest of California that the Colorado Indians were Aztecs, driven from Mexico at the time of the conquest of Cortez. He thinks the circle represents their ancient city, and the water spoken of refers to the surrounding lakes. This idea derives some plausibility from the fact, mentioned by Alargon, that, in his memorable expedition up the Colorado River in 1540, he met with tribes that spoke the same language as his Indian interpreters, who accompanied him from the City of Mexico, or Culiacan.