Fort Irwin & Beyond

A geoglyph is a ground design created by arranging or removing surface materials so the figure appears when viewed from above. In desert settings, this usually means placing or clearing pavement stones, exposing lighter soil, or scraping shallow lines that catch low-angle light. Mojave examples tend to occupy quiet, stable surfaces such as old lake margins, bajadas, ridgelines, and mesa tops. Their age is difficult to determine without stratified artifacts, and they usually appear in liminal settings that suggest signaling, marking, ceremony, or boundary use.

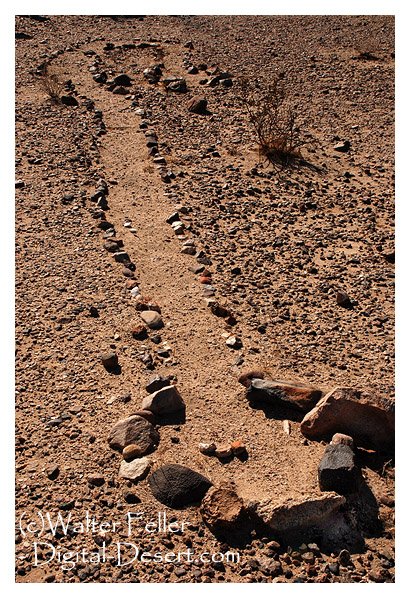

Mojave Desert geoglyphs are scattered and subtle, blending with the surface rather than dominating it. They are created by repositioning varnished stones or removing surface layers, forming sinuous lines, circles, meanders, keyhole forms, and occasionally serpentine figures. Most notable examples can be found in the eastern and central Mojave, where travel corridors, ancient water sources, and basin edges converge. Documented sites are located at Fort Irwin, along the Amargosa drainage, near the Lower Colorado River region, and within ancient lake basins such as Cronese, Soda, and Silver. These figures are commonly twenty to sixty feet long or wide. They are not dramatic from the ground; they reveal their form from oblique or aerial views. Many alignments appear to mark direction, vantage, or symbolic forms rooted in local cultural landscapes. Research is limited by erosion, restricted access to lands, and the scarcity of datable material.

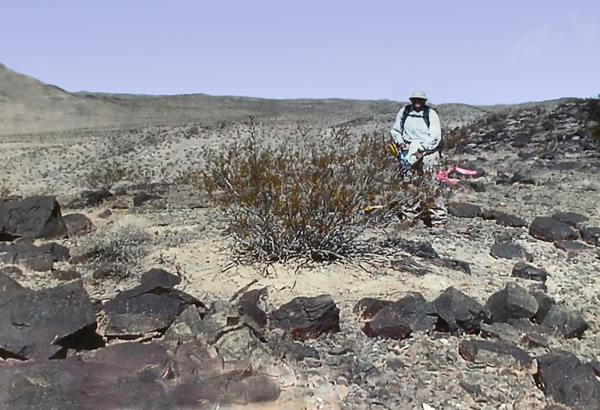

Geoglyphs at Fort Irwin became known only after archaeologists expanded survey work into newly added training lands. Earlier work on the site documented petroglyphs, pictographs, and small rock circles, but newer surveys revealed another category of rock art: broad surface alignments set directly into the desert pavement. These geoglyphs consist of fist-sized stones arranged into straight lines, curves, swirls, and branching patterns covering portions of pavement roughly a quarter of an acre in size. They sit so low and blend so closely in tone with the surrounding ground that they remain almost invisible until someone familiar with desert varnish and pavement structure points them out. Artifacts and oxidation patterns provide relative age clues, though no firm dates are given.

Archaeologists describe the Mojave landscape as highly readable, with scars, signals, and surface changes preserved by aridity. In this setting, rock alignments are found on stable pavements, old lake margins, and gentle rises where water once flowed across the ground. Fort Irwin sits within that framework: ancient lake basins, remnant shorelines, and corridors that once linked seasonal camps. Nearby lithic scatters suggest long-term movement associated with water, game, and travel. Interpretations of the geoglyphs remain limited. Some broken quartzite fragments hint at possible ceremonial use, but the exact meaning remains unknown. Cultural memory tied to such features has not survived, and researchers avoid overreaching beyond what the land itself reveals.

Within the broader Goldstone basin sector of the installation, survey data also note a low ridge with surface materials arranged into a curving alignment that may represent a stylized serpent or directional form. Its placement on a quiet slope between pavement and basin edge fits a familiar Mojave pattern in which subtle figures mark routes, thresholds, or vantage points without leaving associated domestic remains. Features of this kind are typically visible only from an angled view, where dark varnished stones contrast with lighter soil. Because the land is part of an active training area, precise locations are protected, and access is restricted to guided visits. As with other prehistoric sites on the post, Fort Irwin treats these alignments as resources to be safeguarded.

Together, the abstract pavement figures and the additional curving alignment illustrate how ancient travelers marked the basin edges and crossings of the central Mojave. They show that even in a landscape that seems empty at first glance, the ground carries the record of movement, gathering, and intention shaped into the surface itself.

Core Bibliography: Mojave Geoglyphs and Rock Alignments

Allen, Mark W. 1991. Archaeological Investigations at Fort Irwin. Fort Irwin Cultural Resources Program.

Basgall, Mark E. 1993. Chronometric Studies in the Mojave Desert. Publications in California Prehistory 34.

Clewlow, C. William Jr. 1976. Prehistoric Trails of the Lake Mojave Region. UC Archaeological Research Facility Report 30.

Davis, Emma Lou. 1978. The Ancient Californians: Rancholabrean Hunters of the Mojave Desert. Ballena Press.

Fort Irwin Cultural Resources Program. Various Survey Reports and Inventory Summaries, 1980s to present.

Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex. Cultural Resources Overview Studies, 1990s–2000s.

Heizer, Robert F., and Martin A. Baumhoff. 1962. Prehistoric Rock Art of Nevada and Eastern California. University of California Press.

Minor, Rick. 1987. Intaglios and Ground Figures of the American Southwest. American Rock Art Research Association.

Schaefer, Jerry. 1995. Cultural Resource Management Studies at Fort Irwin, California. ASM Affiliates.

- U.S. Army, Fort Irwin Cultural Resources Program. Survey reports and site documentation for expanded training lands, various years.

- Sutton, Mark Q., and Jill K. Gardner. Patterns of Mojave Desert Prehistory. Nevada State Museum Anthropological Papers, 1997.

- Warren, Claude N., and Robert H. Crabtree. Prehistory of the Southwest and Great Basin. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 11, Great Basin. Smithsonian Institution, 1986.

- Draut, Amy E., et al. Late Pleistocene lake histories in the Mojave River and Amargosa Basin region. USGS Professional Papers and Open-File Reports, various years.

- McCarthy, Daniel. Ground figures of the Mojave and Colorado Deserts. In Rock Art Papers, San Diego Museum of Man, various volumes.

- GSA and USGS publications on desert pavement formation, varnish development, and surface stability relevant to geoglyph preservation.

- California Department of Parks and Recreation. Archaeological surveys within the Mojave Desert region, assorted site records.

Special thanks to Russell Kaldenburg