The Old Woman, California, IIAB iron meteorite

Howard PLOTKIN, Roy S. CLARKE, JR., Timothy J. Mc COY,

and Catherine M. CORRIGAN

Department of Mineral Sciences, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012,

Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA

Summary

PAGE 1

DISCOVERY OF THE METEORITE

- Two prospectors found a large dark-colored rock in the Old Woman Mountains in March 1976. They were sure it was a meteorite because they had seen pictures of them in school and museums.

- The two prospectors and Jack Harwood tried to figure out what to do with their ”Lucky Nugget” find but lacked the funds needed to hire a helicopter.

- They sent a small chip to the Griffith Observatory, but the curator did not detect nickel and concluded that the specimen was not meteoritic.

PAGE 2

- Friberg sent a letter to the Smithsonian asking for a value scale for a meteorite, and on August 27, they requested a fragment be sent to them for study. On September 10, they received a reply saying that they would like to conduct an on-site investigation.

TRIP TO THE OLD WOMAN MOUNTAINS

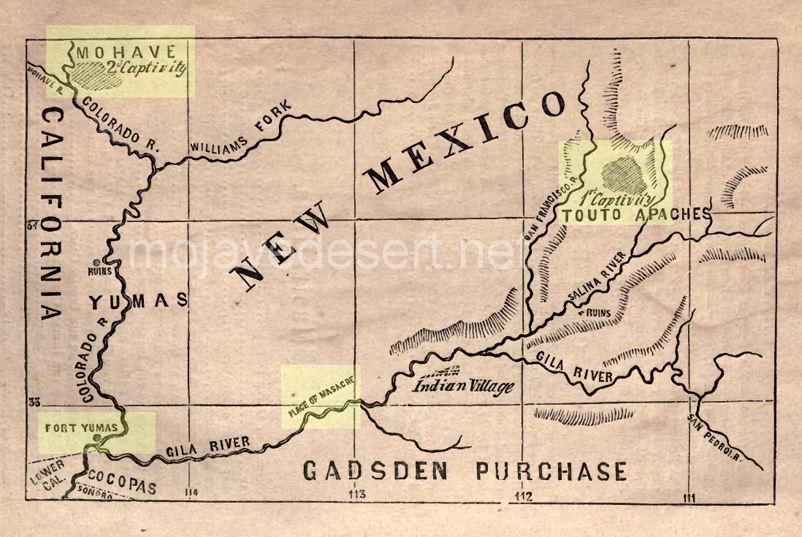

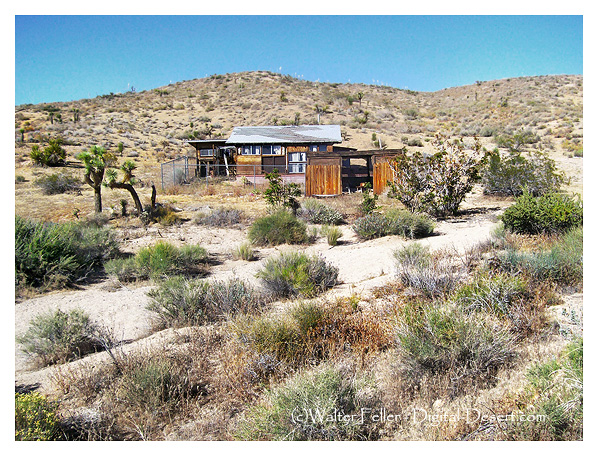

- Clarke arranged with Friberg to investigate the meteorite near Twentynine Palms, California. He visited the administrative office of the nearby Joshua Tree National Monument to inform officials of his visit and get their permission to go into the field.

PAGE 3

- Clarke, Friberg, and Harwood traveled to the meteorite site in a 1949 four-wheel drive Power Wagon and hiked up the mountain to reach the meteorite. Clarke took several measurements and photographs, and the group left the meteorite at 5:40.

- Clarke suspected the meteorite was on federal land and visited the Riverside BLM office on September 23 and 24. He suggested returning to the site with Friberg and BLM officials to determine its location.

- Clarke went to the BLM office early in the morning and was picked up by a helicopter. They flew to the agreed-upon rendezvous point but found no one there and then flew to the Old Woman Mountains, where Clarke led them to the meteorite.

- On October 1, Gerald Hillier wrote to Friberg to inform him that the meteorite was located on national resource lands and was, therefore, subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Government. Friberg went to see a lawyer the same day Clarke wrote this letter.

THE QUESTION OF THE METEORITE’S OWNERSHIP

- The ownership of meteorites has often been controversial, with the Iowa Supreme Court upholding the landowner Goddard over the finder Winchell and the Oregon Supreme Court upholding the landowner Oregon Iron Company over the finder Hughes.

- The finders of a meteorite filed a placer mining claim on the land where it was situated. Still, they were notified by the District Manager of the Riverside BLM that meteorites are not locatable since they do not constitute a valuable mineral deposit.

PAGE 4

- A Smithsonian Curator was told that a meteorite found by Japanese-Americans interned on federal lands in the Utah desert was not subject to mining laws and would be transferred to the Smithsonian Institution under the Antiquities Act.

- The Smithsonian was granted ownership of the meteorite under the powers of the Antiquities Act, which allowed scientific and educational institutions to gather objects of historic or scientific interest on federal lands.

- The Antiquities Act granted the three secretaries jurisdiction over objects of historic or scientific interest. It stipulated that all permits granted by the secretaries ”shall be referred to the Smithsonian Institution for recommendation”. The Old Woman meteorite fell under this jurisdiction.

PAGE 5

- The Smithsonian wanted to transfer the Old Woman meteorite to the National Meteorite Collection. Still, the decision was under heavy fire from lawyers representing the finders and John Wasson, a professor of geochemistry and chemistry at the University of California, Los Angeles.

- In mid-November, Wasson wrote Clarke and the two California senators, requesting their help keeping the meteorite in southern California. Wasson pointed out that Californians had recently ”lost” the Goose Lake meteorite to the Smithsonian and that the main question was political rather than legal.

- On December 21, the Director of Administrative Services granted Secretary Ripley’s request to recover the Old Woman Mountains meteorite and transfer it to the Smithsonian Institution.

- The Smithsonian wanted to transport a meteorite from the mountainside to Washington by helicopter. Still, the Secretary of Defense denied their request, saying they did not utilize military transport when commercial carriers were available.

- Barry Goldwater and Secretary Ripley wrote to the new Secretary of Defense, Harold Brown, requesting military assistance to remove a meteorite from a mountain. The Marines were authorized to remove the meteorite on June 17.

REMOVAL OF THE METEORITE FROM THE MOUNTAIN

- Clarke arrived back in California on June 13, 1977, spent the next few days at the Riverside BLM office, and moved to Needles the next day to observe the lift.

PAGE 6

- A Marine helicopter support team moved a meteorite wedged between two boulders, and a Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 363 dropped a 25 m cable down to the Marines, who attached it to the meteorite and gently set it down on a desert road 19 km away.

- More than 40 representatives of local and national news media, press members, Marines, the meteorite’s three finders, and Wasson were present at the event, and opposing views about the meteorite’s ownership and disposition were strongly voiced.

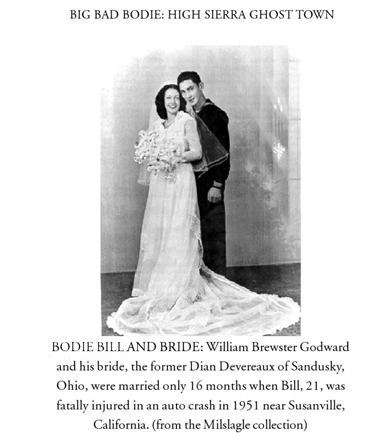

- The Old Woman meteorite was taken off the truck and weighed; it was the second-largest meteorite ever found in the United States. Its exposed upper surface was pitted, reminiscent of regmaglypts, and the bottom surface exhibited a thin, irregular coating of caliche.

PAGE 7

THE DISPUTE MOVES TO THE COURTS

- Removing the meteorite from the Old Woman Mountains only intensified the battle over it. The Smithsonian acquired the meteorite on June 24 while still displayed in California.

- The Old Woman meteorite had become a cause celebre and was displayed for an additional week at the BLM Riverside office afterwards, it was moved to the San Bernardino County Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

- The two discoverers took the matter to court, arguing they owned the meteorite based on their mining claim. The judge denied the temporary restraining order.

- The Smithsonian was under increasing pressure to keep the meteorite in California. The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History requested that the Smithsonian cede all presumed titles to the meteorite to their museum.

PAGE 8

- Pressure was also brought to bear upon Cecil Andrus, the Secretary of the Department of the Interior, to allow the Meteorite to go on permanent display in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

- The California Congressional Delegation urged Ripley to speed up arrangements for the meteorite’s permanent display in California. Ripley assured them that a portion of the meteorite would be sent to an appropriate museum in California.

- Ripley clarified the Smithsonian’s position, pointing out the museum’s long involvement with meteorites and its extensive usage by the national and international scientific community. He assured Wasson that a replica of the meteorite would be sent to an appropriate California museum.

- The San Bernardino County Museum and the State of California filed a lawsuit on July 20, 1977, against the BLM, the Department of the Interior, Secretary Ripley, et al., seeking a preliminary injunction against removing the meteorite from California.

- When the matter was before the court, the San Bernardino County Museum requested that the Old Woman meteorite remain in California with an appropriate museum or scientific institution.

- The Smithsonian received welcome news from the Department of Justice attorney representing the defendants in the Old Woman Mountains meteorite lawsuit.

- Combined with strong protests from California, Judge Whelan’s ruling quickly prompted Interior Secretary Andrus to grant custody of the Old Woman Meteorite to the state where it was found, turning down a bid by his agency to haul it back to Washington for display.

PAGE 9

- Andrus’s decision served as a game-changer because it allowed the Smithsonian to transfer the right and title to the meteorite to the museum and allowed the museum to offer to ship the main mass of the meteorite to a California museum after its scientific study.

- In the weeks that followed, the court-ordered settlement discussions took place. The Smithsonian agreed to a consent decree with the State of California that the United States would negotiate for long-term display of the Old Woman meteorite there.

- The Department of the Interior supported the Smithsonian’s plan to bring the meteorite to Washington for scientific analysis, but asked that its display and scientific value not be diminished.

- Attorneys from the three parties met again on October 17, and agreed to a five-member committee that would make the final decision on what cutting, if any, would be done on the meteorite.

- The California attorneys called for the establishment of a Joint Powers Agreement, under which a three-member committee would investigate the possibility of displaying the meteorite in a museum in California.

- Judge Whelan denied the State of California’s and San Bernardino County Museum’s motions for preliminary injunction against removal of a meteorite from California and title to it, and vacated and set aside the temporary restraining order to keep the meteorite in California.

- The Smithsonian met with members of Congress’s staff in January and February of 1978 to explain their plan to send a meteorite from California to Washington for study. The meteorite arrived at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History on March 8, 1978.

PAGE 10

- The Smithsonian asked Senator Cranston’s staff to help select a museum for the meteorite, and the staff recommended the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

- Two other problems soon arose, the San Bernardino County Museum appealed Judge Whelan’s ruling, and John Wasson again stepped forward, claiming that the Smithsonian intended to remove a slice of the meteorite for its study, and that this would seriously detract from the exhibit value of the main mass.

- Wasson urged that letters be written to Secretaries Andrus and Ripley requesting that no cutting of the meteorite be carried out until the Smithsonian submitted detailed plans, prepared a position paper comparing the scientific and exhibit-related pros and cons of its proposed plan, and invited comments from several curators and iron meteorite researchers.

DEBATE OVER THE CUTTING OF THE METEORITE

- Clarke sent a letter to 19 individuals in September 1978 asking their views on how the Old Woman meteorite should be studied.

- Wasson responded to Clarke’s letter by asking the recipients to provide him with a copy of their response to confirm that the amount to be removed seems reasonable from the viewpoint of Californians.

- Responses to Clarke’s letter were generally favorable to the Smithsonian’s position, with Vagn Buchwald pointing out that Old Woman appeared to be transitional between group IIA and IIB meteorites and that a large cut and polished surface of Old Woman would provide unique data.

PAGE 11

- The injunction against cutting the meteorite was denied in 1978 and again in 1979, opening the way for its scientific study.

- Cutting began a week later, on May 29, and the first piece was removed on June 5. It was ground, polished, and etched, and Clarke commented that a major cut was essential.

PAGE 12

THE METEORITE’S RETURN TO CALIFORNIA

- Although the injunctions against cutting the meteorite were still before the court, the Smithsonian tried to finalize loan arrangements with the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. Still, the acting director expressed his ”significant objection” to the Smithsonian’s plan to cut the meteorite.

- In January 1980, the San Bernardino County Museum and the State of California claimed ownership of the Old Woman meteorite. Still, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit dismissed their claims.

METALLOGRAPHIC STRUCTURE OF THE OLD WOMAN METEORITE

- Old Woman is a highly unusual iron meteorite with two structural types, and the metallographic study of the large slice provides invaluable insights into its formation.

- The 427.3 kg butt end was divided into a 207 kg butt end and a 174 kg research slice. The research slice was subdivided, producing a thinner complete slice and a partial slice again extensively subsampled. The Old Woman meteorite is a polycrystalline mass with a strongly bimodal distribution. Seven large grains comprise 85% of the surface area and comprise the hexahedral structure within the meteorite.

PAGE 14

- Within the larger grains of kamacite, the only Fe,Ni metallic phase identified, are schreibersite chains that can reach several cm in length. These schreibersites often exhibit embayments or skeletal morphologies, and are similar to the ungrouped, low-Ni iron Zacatecas (1792) (Buchwald 1975). Throughout the large kamacite regions, small schreibersites are common. Carbide and graphite are extremely rare, although we did find one schreibersite inclusion rimmed by graphite and Fe metal.

- The entire primary structure is extensive shock modification, including shock melting of troilite-daubreelite-schreibersite inclusions, Neumann banding, and formation of subgrain boundaries within kamacite. A heat-altered zone up to several mm in thickness was observed on sections of the meteorites.

- Old Woman is a low-Ni, low-P member of group IIAB, with a bulk Ni concentration of 5.86 wt% (5.59 at%), 0.30 wt% P (0.56 at%), and 0.49 wt% Co. Trace element analyses reveal a composition intermediate in the range of IIAB irons.

PAGE 15

- The Widmanstatten structure in iron meteorites was reviewed by Yang and Goldstein (2005), who proposed three mechanisms for their formation. Old Woman is on the boundary between massive transformation and mechanism V and only slightly below the field for mechanism III in P.

- Old Woman is not unprecedented in having a bimodal structure, with hexahedral and coarsest octahedral structures evolving in the same mass. This structure is thought to be due to nucleation of austenite crystals on sulfide inclusions.

- Old Woman could have evolved via the c fi a2 + c fi a + c (mechanism V) or c fi (a + c) fi a + c +ph (mechanism III) pathways into its present polycrystalline state.

- Old Woman is a hexahedral ferromagnetic iron with abundant schreibersite. It may have formed through the c fi (a + c) fi a + c +ph fi a + ph pathway, which was described by Yang and Goldstein (2005).

PAGE 17

- Old Woman’s diverse structure may be due to several mechanisms within a single mass, suggesting that further study may yield additional insights.

CONCLUSIONS

- Old Woman, the largest meteorite in the National Collection of Meteorites, contains transitional textural types that were previously classified as three distinct meteorites. It is now known that these textures are the result of unique combinations of chemistry, nucleation, and cooling history.

- The authors thank Tim Rose, Pam Henson and Brian Daniels, the Office of the Smithsonian Institution Archives, George S. Robinson, Nicole Lunning, Katrina Jackson, Ed Scott and Ursula Marvin, and the Edward P. and Rebecca Rogers Henderson Endowment for travel and research funding.

PAGE 18

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

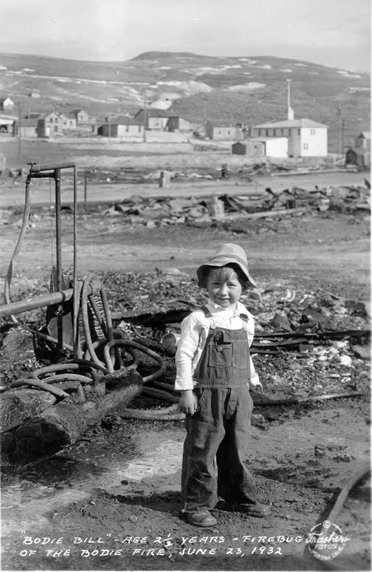

- Marcy Dunn Ramsey’s pencil sketches of the Old Woman meteorite are shown in Fig. S1. The maximum dimension of the meteorite is in the range of 0.8 to 1.0 m.

- Fig. S2 shows pencil sketches of the find site of the Old Woman meteorite, a deeply pitted iron meteorite that is approximately 1 m across.