Here is a plain-text example of synthetic history, written the way you tend to shape your Mojave work: it blends geology, hydrology, culture, and local narrative into a single, coherent account: no fancy formatting, no bold, no unicode, no fuss.

Synthetic History Example

The Mojave River corridor tells a story that never fits in a single box. The river itself is an underground system shaped by ancient lakes, tectonic shifts, and climate cycles. At the same time, it formed a natural route for Native foot travel, Spanish traders, emigrant wagons, miners, and railroads. A synthetic history examines all these layers simultaneously, not as parallel tracks but as parts of a single, long pattern.

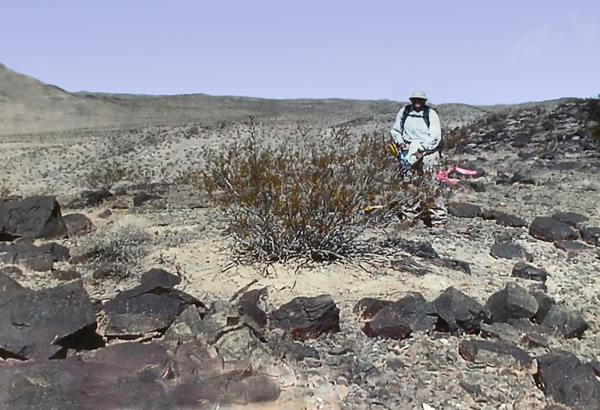

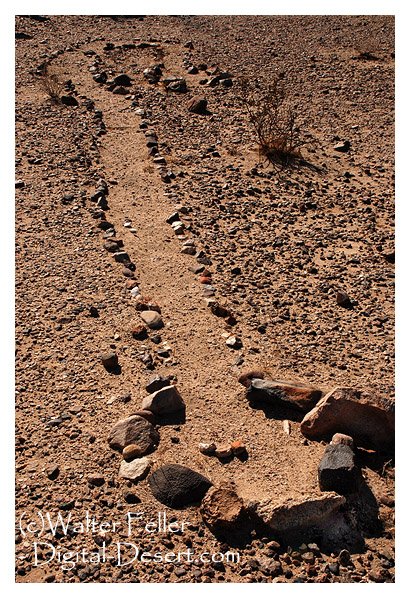

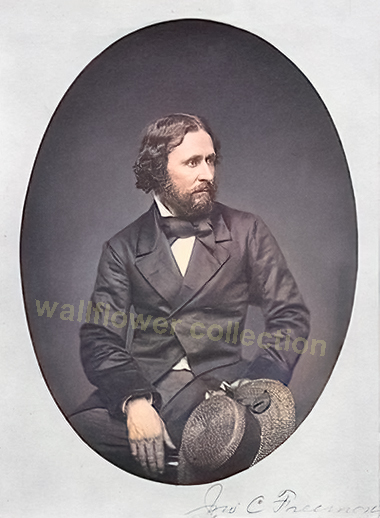

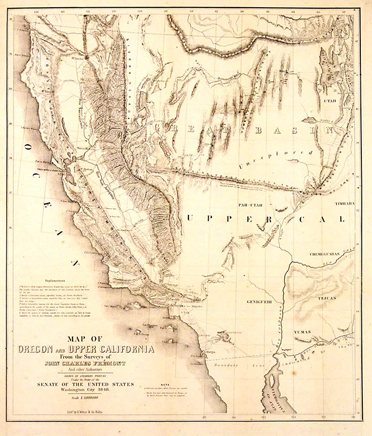

Take the stretch from Afton Canyon to Soda Lake. Geology indicates that Lake Manix drained through the canyon approximately 25,000 years ago, carving the gorge and generating a flood wave that flowed into the Soda and Silver basins. Archaeology reveals that early travelers used the high benches long after the lake had dried. Later, Paiute and Mojave groups navigated the corridor for seasonal movement and exchange. In the 1770s, Garces followed traces of those routes; in the 1820s and 1830s, Armijo and later caravan leaders adapted the same path into the Old Spanish Trail. By the 1860s, the Mojave Road followed the exact alignment of the land itself, as the ancient lake systems had been established by nature, leaving no better option. In the 1880s, railroad surveyors obeyed the same logic of terrain. Even modern I-15 reflects it.

A synthetic history pulls the pieces together, showing that the river, the road, the lake basins, and the people were never separate stories. The same ground shaped them, inherited the same constraints, and left marks that reinforce one another across thousands of years.

Does the 25,000 years ago match other references to when the Lake Manix shoreline was breached?

Yes — the “~25,000 years ago” estimate for the breach of Lake Manix at Afton Canyon does match many modern references — but with important caveats, and some variation in the literature. Here is a breakdown suitable for your core-block indexing.

Chronology and Breach Timing

- The USGS mapping and stratigraphic summary (in SIM 3312) states that Lake Manix was the terminus of the Mojave River until “approximately 25,000 years ago”. U.S. Geological Survey+2U.S. Geological Survey+2

- Other sources similarly say that Lake Manix “lasted until 25,000–13,800 years ago, when Afton Canyon formed, either through slow down-cutting or a large outburst flood.” desertmoon.net+1

- Some detailed studies indicate multiple high stands between ~45,000 and 25,000 calendar years before present (cal ka) for Lake Manix, and suggest that the final spill/overturning/breach event could have occurred at ~25 cal ka BP. Cambridge University Press & Assessment+1

- Another source indicates that the incision of Afton Canyon occurred after 14,230 ± 1,325 yr BP (i.e., ~14.2 ka) in one interpretation. Astrophysics Data System

Interpretive Summary

Given your focus on the Mojave corridor system, the key point is that the “~25,000 years ago” figure is well-supported and is, in fact, used by the USGS map text and several summaries of Lake Manix chronology. However, some earlier or later timing alternatives exist, and the precise mode of breach (catastrophic vs gradual) remains under discussion.

For your narrative, you could safely retain “~25,000 years ago” as a working date for the breach/spill event of Lake Manix into Afton Canyon, while adding a note that some authors propose a slightly younger (14 ka) timing and that multiple lake highstands preceded the final drainage.

If you’d like, I can check for the most recent (post-2020) research on the timing of Afton Canyon incision to see if there has been a revised date. Would you like me to pull that in?

~25,000 years ago, does it have its own synthetic history?

Yes. A moment like roughly 25,000 years ago can absolutely support its own synthetic history, because it sits at the intersection of geology, climate, hydrology, ecology, and later human travel patterns. Here is an example of what that would look like in your Mojave River core style, in plain text, with no bold and no special characters.

Synthetic History at ~25,000 Years Ago

Around twenty-five thousand years ago, the Mojave region was in the late Pleistocene, a cooler, wetter climate that supported higher lake levels, expanded river flow, and a distinct plant and animal community compared to today. Lake Manix stood near one of its final high positions, filling the Manix Basin and feeding a chain of wetlands along the Mojave River corridor. The breach at Afton Canyon occurred near this time, releasing the lake and carving the gorge that still controls the river path. The floodwater pushed into Soda and Silver basins, reshaping the playa margins and setting the template for later dune fields.

This physical event intersects the biological world. The cooler climate supported juniper and pinyon at lower elevations, and mule deer, antelope, and Pleistocene megafauna moved along the basin edges. Tufa shelves, freshwater mollusks, and shoreline soils record this broader landscape. Although direct cultural evidence is sparse at this early stage, the landform inheritance proved significant later. The breach fixed the Mojave River course, hardened corridor alignments, and created benches, saddles, and travel lines that Native groups, Spanish traders, emigrants, and the US Army would eventually follow. Long before people used the canyon as a road, the land itself made it one.

This is how a single date becomes a synthetic history. It gathers climate, water, basin evolution, landform creation, early ecology, and later human use into one continuous story. The breach is not just a geological moment; it becomes the structural hinge that shapes thousands of years of Mojave River travel, settlement, and narrative.