Introduction

This synthetic history offers a short, integrated view of how a place or event may have developed over time. It draws on known facts, adds reasonable connections, and presents a straightforward narrative that helps the reader see the larger pattern behind the details.

Harper Lake began as a shallow Pleistocene basin fed by the changing Mojave River system. As the climate shifted and Lake Manix drained, water reached the Harper basin only in rare pulses, leaving broad mudflats and signs of older shorelines. Early travelers used the dry lake as an open landmark between Barstow and the Fremont Valley. Ranchers later crossed it while moving stock between seasonal ranges. In the twentieth century, power lines, ranch roads, and the airfield at Lockhart marked its edges, but the basin itself stayed quiet. What began as an ancient lake became a wide, dependable reference point in the western Mojave.

Diagram version

Pleistocene Basin

(formed during wetter Mojave River phases)

|

v

Lake Manix Drainage

(water reaches basin in rare pulses)

|

v

Broad Mudflats

(old shorelines, dry lake surface)

|

v

Travel Landmark

(open guide between Barstow and Fremont Valley)

|

v

Ranch Use

(stock crossings, seasonal routes)

|

v

Modern Markers

(power lines, Lockhart airfield, access roads)

|

v

Present Basin

(dry, stable landmark in the western Mojave)Essay

Harper Lake is one of those quiet western Mojave basins that tells a long story without saying much. Its history begins in the late Pleistocene, when the Mojave River behaved differently, and water sometimes pushed farther west than it does today. After Lake Manix drained, the river wandered across its basin system in unpredictable pulses. During the wetter periods, some of that water reached the Harper basin, leaving layers of fine silt and clay, smoothing the floor, and marking low shoreline benches on the basin walls. These old lake margins still sit a few feet above the flats, showing where storms, climate, and river pathways once made a shallow lake in a place that is now dry most of the year.

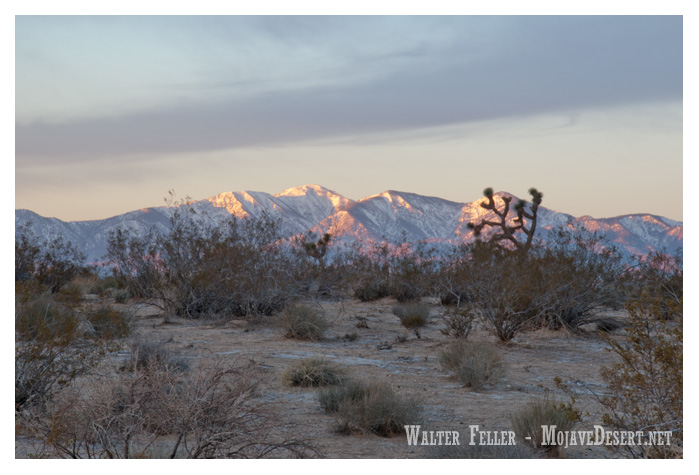

As the climate warmed and dried, Harper Lake shifted into a different role. Its connection to the Mojave River became rare and temporary. Water arrived only through heavy storms, brief pooling, or scattered sheetflow that vanished as fast as it came. By the Holocene, the basin had settled into the pattern we recognize today: a vast playa surrounded by creosote scrub, saltbush patches on the margins, and a wind-polished surface that reflects the sky when it is dry and mirrors it when it is briefly wet.

This kind of history fits perfectly with the synthetic examples we started building. In those early models, we traced how simple features in desert country begin as natural formations and slowly take on meaning as people start using them. Harper Lake followed that path. Long before written history, Native travelers crossed its edges as they moved between springs and gathering places. The lake itself offered little water, but its openness made it a dependable marker between the Mojave River corridor and the Fremont Valley routes.

When ranching spread into the region, the basin became part of seasonal stock drives. The flat surface offered a straight line across the land, and the margins gave access to scattered grazing after rare rains. Later, freighters and early motorists used the dry lake the same way: as a clear, recognizable point in a vast landscape where a person needed all the help they could get to stay oriented. The open horizon, the straight edges, and the bare floor served as practical signs that they were on the right course.

By the twentieth century, modern structures began to appear around the basin. Power lines crossed the margins. Utility roads threaded across the flats. The airfield at Lockhart took advantage of the open terrain. Yet even with these additions, Harper Lake retained its quiet identity. It stayed dry most years, it kept its old shorelines in place, and it remained a stable reference point for anyone who knew the western Mojave.

This is the same pattern our first synthetic histories described: a natural feature shaped by water and climate becomes a guide for travel, a minor stage in ranching and settlement, and finally a fixed part of the regional map. Harper Lake shows that a place does not need deep water or dramatic cliffs to play a long role in desert history. Sometimes a broad, silent basin does the work, carrying its past in its shape and offering direction to anyone crossing the land.

–

Synthetic history disclaimer

This synthetic history blends facts with interpretive narrative to show how events, places, and processes may have unfolded. It is not a primary source and does not replace direct historical records, archaeological findings, or scientific studies. Details drawn from known evidence are kept as accurate as possible, while connecting material is written to provide continuity and context. Readers should treat this as an interpretive aid, not as a definitive account, and consult documented sources for precise dates, data, and citations. This is a learning engine rather than a teaching engine.

Harper Lake Ecology