Mojave Desert Net & Digital-Desert.com

Walter Feller, a retired engineering technician, has spent the past 30 years developing and expanding Digital-Desert.com and MojaveDesert.Net, two extensive resources dedicated to the history, geography, and natural beauty of the Mojave Desert. His work combines research, photography, and storytelling to document the region’s landscapes, historic sites, and ecological significance.

His dedication to preserving and sharing knowledge about the Mojave Desert through these platforms has made him a key figure in desert history documentation.

Introduction

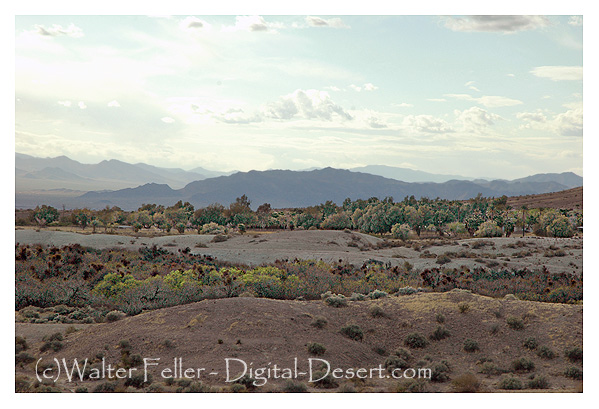

The Mojave Desert is a sprawling, rugged terrain full of history, unusual geology, and varied ecosystems. Two valuable online resources, **MojaveDesert.net** and **Digital-Desert.com**, offer an extensive overview of this interesting region. With coverage ranging from national parks and wilderness areas to ghost towns, historic trails, and natural landmarks, the websites offer detailed guides for adventurers, historians, and nature lovers alike. Suppose you’re interested in desert wildlife and plants, mining history, native cultures, or points of interest. In that case, these websites provide detailed information, interactive maps, and beautiful photographs to make the Mojave tales come alive.

MojaveDesert.net is a comprehensive resource dedicated to the Mojave Desert, offering a variety of information about its geography, history, ecology, and more. The directory tree in the following is not complete but demonstrates While I don’t have access to a complete directory tree of the website, I can provide an overview of its main sections based on available information:

- Home: Introduction to the Mojave Desert, featuring highlights and recent updates.

- Geography: Details about the desert’s location, topography, and significant landmarks.

- Flora and Fauna: Information on the plant and animal species native to the Mojave Desert.

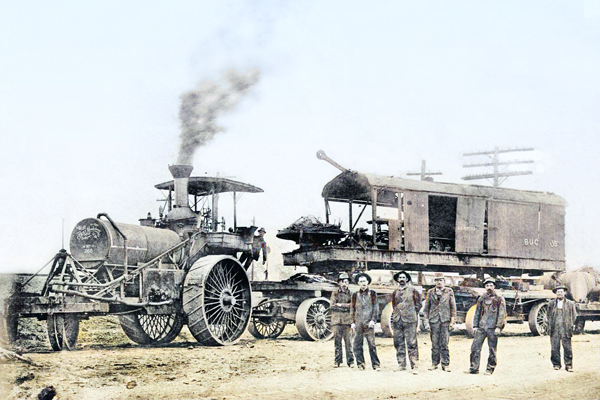

- History: Insights into the cultural and historical aspects of the region, including indigenous cultures, exploration, and settlement.

- Ecology: Discussions on the desert’s ecosystems, climate, and environmental concerns.

- Recreation: Guides and tips for activities such as hiking, camping, and sightseeing in the Mojave Desert.

- Photo Gallery: A collection of images showcasing the desert’s landscapes, wildlife, and points of interest.

- Resources: Additional materials like maps, articles, and external links for further exploration.

For a more detailed exploration of the website’s content, I recommend visiting MojaveDesert.net directly.

MojaveDesert.net is a resource covering the Mojave Desert’s geography, history, ecology, flora, fauna, and recreation. It includes sections on landmarks, indigenous cultures, exploration, environmental concerns, hiking, and photography. The site also offers maps, articles, and external resources.

Digital-Desert.COM

Digital-Desert.com is a comprehensive resource dedicated to the Mojave Desert, offering detailed information across various topics:

- Nature: Explores the desert’s ecology, including its wildlife, plant life, geology, and climate.

- Parks & Forests: Provides insights into national parks like Death Valley and Joshua Tree, as well as lesser-known state and county parks.

- Wilderness Areas: Highlights regions preserved in their natural state, free from human impact.

- Geology & Natural Formations: Discusses the majestic formations and mountain ranges found throughout the Mojave Desert.

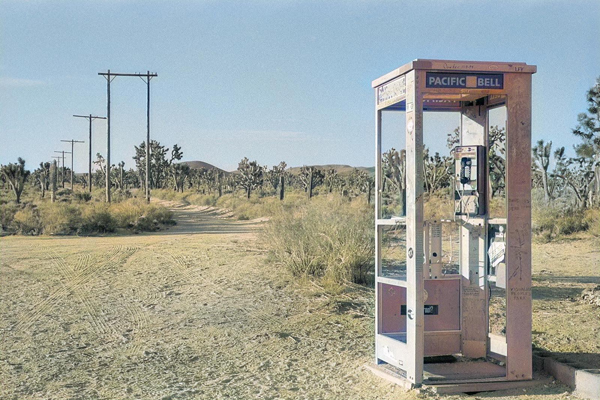

- Points of Interest: Features notable destinations and attractions within the desert.

- Regional Map Guide: Offers an interactive map for navigating the Mojave Desert.

- People & History: Delves into the histories of various groups and cultures associated with the Mojave, including influential figures and native cultures.

- Roads and Trails: Covers historical and contemporary routes, as well as hiking trails and backroads.

- Ghost Towns & Gold Mines: Examines abandoned communities and the mining history that once thrived in the region.

- Communities: Profiles current towns and cities within the Mojave Desert.

The website also features sections on the Mojave River, historic roads and trails, craters and lava flows, petroglyphs, dunes, and dry lakes (playas). Additional resources include a blog, weather information, and a glossary.

digital-desert.com

For a more in-depth exploration, visit Digital-Desert.com.

summary

Digital-Desert.com is a comprehensive resource on the Mojave Desert, covering its nature, geology, history, and points of interest. It includes information on national parks, wilderness areas, ghost towns, gold mines, roads, trails, and regional communities. The site also features interactive maps, historical accounts, and details on wildlife, plant life, and natural formations.

description of these two websites combined

Conclusion

MojaveDesert.net and Digital-Desert.com are two extensive online resources dedicated to exploring the Mojave Desert’s rich history, geography, ecology, and cultural significance. Together, they provide a comprehensive look at the region’s national parks, wilderness areas, ghost towns, historic roads, and geological formations. These sites offer in-depth information on the desert’s plant and animal life, environmental concerns, indigenous cultures, mining history, and notable landmarks. Visitors can also find interactive maps, hiking guides, and photography collections that highlight the beauty and complexity of the Mojave Desert.