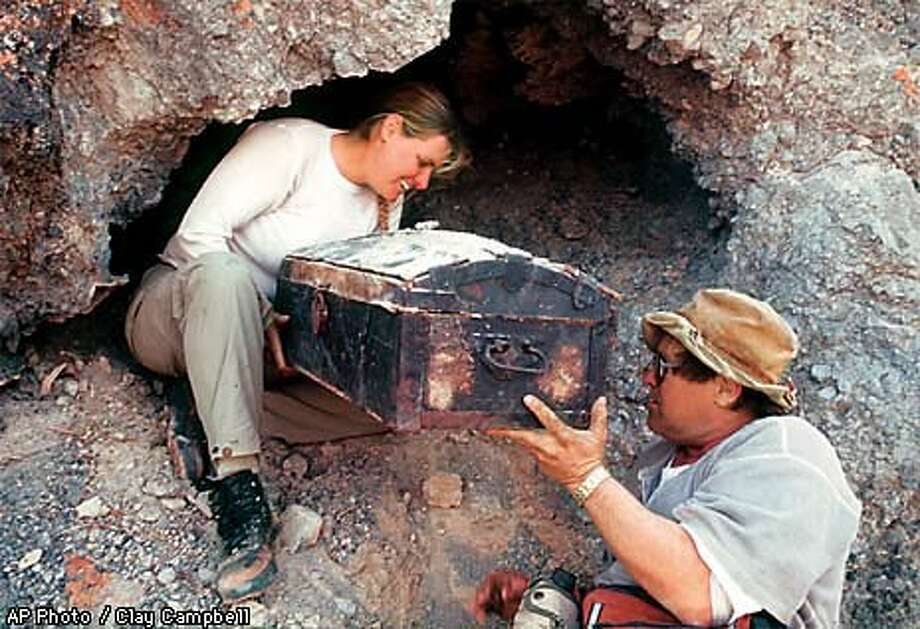

Back in late 1998, Jerry Freeman, an amateur historian with a passion for Death Valley’s old 49er trails, came out of the Panamint Mountains claiming he had found something straight out of a gold rush daydream. Hidden deep inside a cave, he said, was a wooden trunk left behind by the lost ’49ers who famously struggled across Death Valley in 1849.

The box was a curiosity in itself — weathered wood, iron hinges, smelling of dust and old paper. Inside was a jumble of “treasures”: gold and silver coins (most tarnished, some shiny), a hymnal, a flintlock pistol, a pair of baby shoes worn soft with age, ceramic bowls, and even a letter dated January 2, 1850, supposedly written by a pioneer named William Robinson. The letter told a story of hardship and faith as the writer prepared to leave the desert behind. To Freeman, it was the smoking gun of history — proof that the Jayhawker survivors had stashed some of their belongings before moving on.

When he brought the chest to Death Valley National Park headquarters in early 1999, there was real excitement. Newspapers ran breathless headlines about a half-million-dollar find. Historians daydreamed about finally holding personal effects from the very people who gave Death Valley its name.

But almost as quickly, the doubts started trickling in. Some of the coins didn’t match the time period. The word “grubstake” appeared in the letter — a term that historians said wasn’t common until years later. And some items looked suspiciously… fresh. One ceramic bowl still had a price sticker.

Park officials brought in experts from the Smithsonian and the Western Archaeological and Conservation Center. That’s when the story unraveled fast. They found modern polymer glue holding parts together. The tintype photos used a process that wasn’t invented until after 1856. A “Made in Germany” stamp on one bowl could only have existed after World War I. Even the leather on the baby shoes was still soft, which shouldn’t have been possible after 150 years in Death Valley heat.

By the end of January 1999, the Park Service went public: it was a hoax. Not one item in the chest could be proven authentic to the Gold Rush era.

Freeman stood his ground, saying he’d always believe the chest was genuine, maybe “salted” with a few newer items by someone else. But for most historians, the romance was gone. What had looked like a once-in-a-lifetime discovery turned out to be another desert tall tale — one that fooled people just long enough to make them want to believe it.