--

The History of Daggett Garage

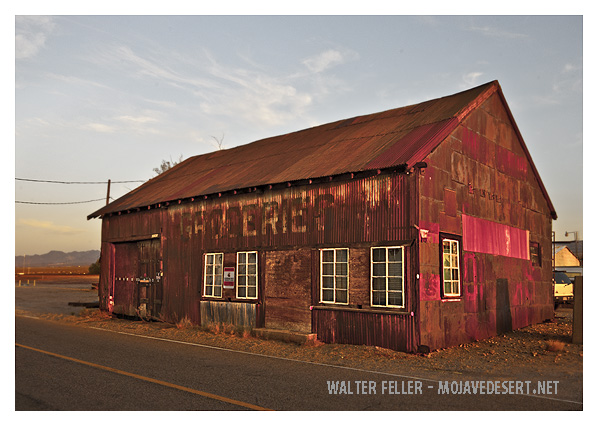

Daggett Garage

Daggett owes its existence to its strategic location on the Mojave River. It became an important stop on the railroad and later on old Route 66. It evolved into a major trading and transportation center, and though the demise of “The Mother Road" and the advent of Interstates 15 and 40 has isolated it to some degree, it still boasts the Marine Corps Logistic Center, the nearby Barstow/Daggett Airport, a fine museum, and a thriving community that ensures its continued existence.

Recorded history of the Daggett area begins with the journal of Father Francisco Garces, who set out on his explorations in 1776. Garces followed the Mojave River, and remarked on the several Indian rancherias in the vicinity of present-day Barstow and Daggett.

In 1829 the Old Spanish Trail was pioneered to connect the Mexican settlements in southern California with the city of Santa Fe. Prior to Mexican independence in 1821 these communities had been under Spanish control. For two decades this trail witnessed the annual passage of large trade caravans that exchanged New Mexican woolen goods for much-prized California horses and mules. The route entered California after passing through Nevada's Pahrump Valley, then proceeded on to Resting Springs, near today's Tecopa, and thence to Salt Spring near the big bend of the Amargosa River. After heading south from Resting Springs there was no water, except for a small hole of vile liquid called Bitter Springs (now located within the boundaries of the Marine Corps AirGround Training Center), until reaching the Mojave River a few miles downstream from modern Daggett. Following the establishment of the Old Government Road (Mojave Road) in 1859, this spot became known as Forks of the Road.

In later years the area was traversed by such illustrious mountain men and trailblazers as Jedediah Smith and Joseph Reddeford Walker, but for the most part it remained a quiet backwater, as did much of inland CaHfornia until the Mexican War and the ensuing California Gold Rush. At the end of the war this territory came under control of the United States, and the annual trade caravans over the Old Spanish Trail came to an abrupt halt. Almost immediately, however, the slack was taken up by increasing numbers of Mormons traveling between Salt Lake City, established in 1847, and the ports of southern California, which served both as a place to obtain things unavailable in Utah and as an entry point for floods of Mormon converts from Europe and the South Seas. Although never a major route to the goldfields, it was still an important gateway for groups arriving in the West too late to dare a winter crossing of the Sierra Nevada, such as the fabled Death Valley 49ers.

As the rush for gold slowed, pioneers of a different sort overflowed into the California countryside. Along with the miners, more and more ranchers and farmers settled the well-watered bottom lands along the Mojave River. As a result of this influx, clashes with the indigenous Indian population became inevitable. This conflict resulted in the establishment of a military post by Major James H. Carleton and troopers of his First Dragoons in 1860. Camp Cady, named for Carleton's friend and fellow soldier Albemarle Cady, was located on the Mojave River a few miles west of Forks of the Road, which has been previously mentioned. In 1859 the Army established Fort Mojave, on the Arizona side of the Colorado River near today's Bullhead City. Soldiers stationed here protected mail, travelers, and military traffic from the warlike Mojave Indians, who controlled the only good ford on the Colorado for a hundred miles north of Yuma. Forks of the Road marked the juncture of the Old Government (or Mojave) Road, connecting Fort Drum and the port of Los Angeles with Fort Mojave, and the Old Spanish Trail, which by this time had largely come to be known as the Salt Lake or Mormon Road.

Along with the farmers and ranchers came a number of prospectors. Mining was undertaken at Salt Spring as early as 1850, and by the following decade the entire region was being scoured by prospectors. By the 1870s strikes by these miners and the resulting lines of transportation and communication spurred a huge influx of travelers to this section of the desert. Small waystations sprang up to serve the sojourners, among them Lane's Crossing (Victorville), Grapevine, Cottonwood, Point of Rocks (Helendale), and Oro Grande. Near the site of toda/s Marine Corps Logistic Center (Nebo Annex) was a spot called Fish Ponds. Here, the Mojave River flowed on the surface and formed a large basin said to contain fish. Today, the groundwater has been drawn down considerably and the ponds are no longer visible. Despite all this activity in the immediate vicinity, Daggett's heyday would not come until the 1880s.

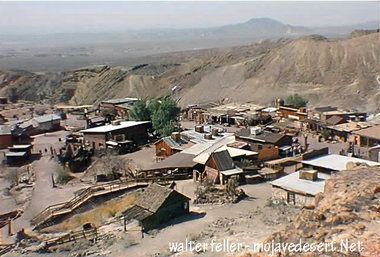

The history of Daggett cannot be addressed without mentioning the boomtown of Calico, a few miles to the north. Rich silver deposits were found here in 1881, and the Silver King claim was located. In 1882 the camp began to boom as the Silver King came into full production. The name of the new town derived from the varicolored rocks in the area, which were said to remind the miners of a piece of calico cloth. A post office and a weekly newspaper were quickly established. The county created a school district and voting precinct, and a well was dug at nearby Calico dry lake to provide the new community with water. Much of the town was destroyed by fire in 1883, but it soon revived, eventually reaching a population of over 2,500. Development peaked in 1884-85. By this time the village had come to consider itself quite civilized, and the event of the season was the May Day Ball and Ice Cream and Strawberry Festival, held in the town hall by the ladies of Calico. Unfortunately, in 1885, as commemorated by a 1976 Billy Holcomb Chapter plaque, the event was broken up at two a.m. by a shootout between two groups of rival miners, and “ended with the slinging of eggs and lead."

Daggett was widely expected to become the premier settlement in this part of the desert. Indeed, by the turn of the century it was larger than either Barstow or Victorville. The camp's seemingly preeminent place was truly assured, however, when the rails came in 1882. The infant community immediately became the transportation and supply center for mines and mining districts farther to the north and east. The station, originally called Calico, was soon renamed for John Daggett, California's lieutenant governor from 1883 to 1886. Even as production as the Silver King began to wane, mills and processing plants near the river were constructed and expanded, the largest of these boasting 60 stamps and electric power. In 1888 the narrow-gauge Calico Railroad was built to connect the camp with the Santa Fe main line at Daggett in order to more efficiently move the ore from mine to mill. For many years during this era, Daggett was the busiest, toughest, and most notorious town in the Mojave Desert.

In 1892 the price of silver dropped precipitously, and mining activity at Calico came nearly to a standstill. The Calico Railroad was abandoned and the narrow-gauge rails were subsequently pulled up in 1903. Daggett's fortunes might have taken a decided turn for the worse but for the discovery of rich deposits of another, more humble mineral-borax.

In 1880, while prospecting in Death Valley after leaving the declining mining camp of Panamint City, a Frenchman named Isadore Daunet and a few companions almost lost their lives in the desert, resorting to killing their pack animals and drinking their blood in order to survive. A year later, hearing of the borax strikes that would later become the Harmony Borax Works, Daunet remembered seeing the white mineral in his travels and returned to file a claim on 270 acres of borax flat at Eagle Spring on the floor of Death Valley. His first attempts consisted of simply scooping up raw borax and packing it out on muleback. This impure borax returned only 17 cents a pound, and Daunet set out to improve the efficiency of his operation. Journeying to Daggett, he and his partners packed in a 25-foot iron pan and twelve 1,000 gallon galvanized tanks. By boiling and crystallizing the borax, they got a more refined product which reduced transportation costs considerably.

Within a year Eagle Borax Works had processed 260,000 pounds of borax in its primitive refinery. The finished product was freighted out in two-wagon rigs drawn by twelve mules. This was the first borax shipped out of Death Valley. It went to the railhead at Daggett via Wingate Wash and Wingate Pass, Lone Willow and Granite Springs, and Black's Ranch, north of modern Barstow.

William T. Coleman's more famous Harmony Borax Works began operations soon thereafter. He also owned borax properties just south of present-day Shoshone, California. In 1884 Coleman's local competition ceased when Daunet committed suicide in San Francisco and his company folded. The Harmony works was faced with the same transportation problems as Daunet. The borax had to be shipped to the rails at either Daggett or Mojave, both about 165 miles away. A typical round trip by wagon took twenty days.

There is come controversy as to what route was used by the Harmony operation. Some say that the early route was to Daggett, via Saratoga Springs, the Avawatz Mountains, Cave Springs, and Coyote Holes. Others say it was to Mojave. At any rate, in a short time Coleman decided that in order to make a profit he would have to create his own road and freight line. He also needed wagons capable of hauling heavier loads than ever before. To this end, he commissioned his superintendent, J.W.S. Perry, to pioneer a new route to Mojave, and to design the rigs themselves-the world-famous twenty-mule team borax wagons. Big wagons had existed before this, but none as big as Coleman envisioned. Ten wagons were to be built, with the work being done in the then tiny village of Mojave. Since they were probably the biggest wagons ever used, and were so completely successful, a detailed description is in order at this point.

The wagons themselves were to carry at least ten tons apiece. The rear wheels were seven feet in diameter, with an iron tire eight inches wide and one inch thick. The front wheels were five feet high, with the same width as the rears. The hubs were eighteen inches in diameter, and the steel axles were more than three inches square. The wagon beds were sixteen feet long, four feet wide, and six feet deep, with a width across the wheels of six feet. Each wagon weighed 7,800 pounds empty, and cost about $900. The normal outfit consisted of two wagons, hauling a total of about 45,000 pounds of borax, and a third wagon carrying 1,200-gallon water tank. The rig was drawn by a team of two horses and eighteen mules, with the horses, known as the “wheelers", occupying the position nearest the wagons. The conventional wisdom is that the horses were smarter than the mules, but the opposite was almost certainly true. The horses, being bigger and stronger, were better able to push the heavy wagon tongue from side to side. Although borax is a mineral of relatively low value, even a modest 1880s price of 30 cents a pound translated to $600 a ton, so the potential profit from such runs is evident.

For five years, from 1883 to 1888, the wagons hauled borax to Mojave on a regular schedule without a breakdown, an amazing record considering the tonnage carried and the roughness of the road. In 1888 the Harmony operation shut down, and operations were moved to the nominally cooler climate of Shoshone, thus facilitating the crystallization of the borax, which occurred at a temperature of about 116 degrees F. Most of the wagons were bought up and used by other freighters to serve such desert boomtowns as Randsburg, Tonopah, Goldfield, and Rhyolite. Two of them found continued employment at the new camp of Borate.

In 1882, about twelve miles from Daggett, near Mule Canyon, a rich deposit of borate of lime (colemanite) was discovered. William T. Coleman, San Francisco business leader and namesake of the mineral, bought the- claims and developed a mine, but no large-scale production took place. After Coleman's company failed, Francis Marion “Borax" Smith bought the property in 1890, and work began in earnest. The towns of Borate and Marion sprang up near the mines. Twenty-mule teams again hauled borax to the railhead at Daggett. A post office was established at Borate in 1896. Both villages achieved modest success, but their combined populations probably never reached 200. Borate boasted a small business district and a spacious hilltop house for Smith and other visiting officials. The miners often lived in dugouts to escape the desert heat. Longline 20-mule teams drawing their huge wagons were once again a familiar sight in Daggett. Because of the shorter distances involved, a single outfit could move fourteen loads of borax to the railroad in the time it took for a single load on the Harmony-Mojave run. As Borate's output increased, it became necessary to add two more outfits to meet the demand. These wagons were constructed by and leased from Seymour Alf of Daggett. It was during the early days of Borate that the 20-mule teams began to receive nationwide attention. Many publicity photos were taken of the heavy wagons hauling borax from the deposits near Calico to the rails at Daggett.

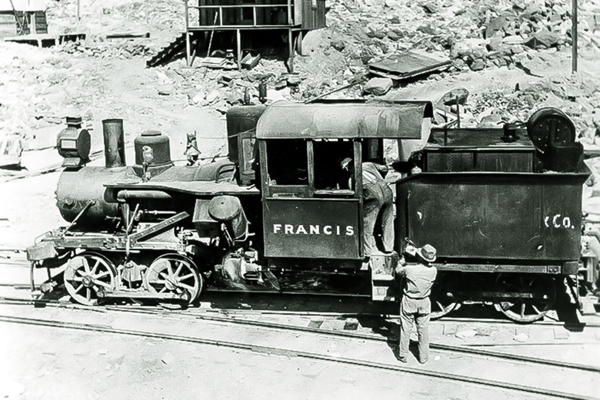

As part of an ambitious plan to tap the world market for borax, in 1898 Smith built a narrow-gauge rail line, the Borate and Daggett Railroad, from the mines to Daggett, as well as a plant at Marion to roast and refine the increasingly low-grade ore. The completion of the line marked the end of an era as the 20-mule teams were retired, replaced by two Heisler locomotives dubbed Francis and Marion. Two of the final borax wagons were to sit abandoned at Daggett for almost twenty years.

Even before the railroad was completed. Smith had decided that the 20- mule outfits were outmoded, and began looking for a more modern and efficient way to replace them. In 1896 he purchased a huge high-wheeled, oil-fired steam tractor and put it to work on the Borate-Daggett run. The mammoth machine, called “Old Dinah,” was not a success. The story goes that the tractor could indeed haul 25-ton loads of borax, but that she dug herself in on soft roads, reared up on her hind wheels on steep grades, and had to be worked on “all night every night” to keep her in running order. On more than one occasion freighters had to take time out from their duties to haul Old Dinah out of holes she had dug herself into. Within a year the tractor was retired, and today is on display outside the gates of Furnace Creek Ranch in Death Valley.

Of the famous teams, the days of Borate were numbered. The quality of the ore continually diminished, and the deposits got harder and harder to work. Smith began building another railroad, the Tonopah and Tidewater, to connect the Santa Fe Railroad at Ludlow with the heretofore undeveloped Lila C. Mine at the eastern edge of Death Valley. There were other, richer claims in the area, but this was the easiest to reach by rail. Miners began work at the Lila C. in 1904, stockpiling ore while awaiting the arrival of the rails. In fact, so much borax piled up that the 20-mule teams were once again called into service. During the summer of 1907 they hauled borax to the end of track even as the rails crept closer to the mine. When the line was completed in August of that year, the wagons were out of the borax business for good. Within a few months. Smith shut down operations in Borate, and the employees there moved to Death Valley. Except for advertising and exhibition purposes, the 20-mule teams were gone for good.

The teams were heavily promoted in the years following the turn of the century. One outfit was exhibited at the World's Fair in St. Louis in 1904. In 1916 the old wagons at Daggett were spruced up, mules were purchased and trained, and the rig was sent east for an extended publicity tour. In 1937 another outfit went to San Francisco to celebrate the opening of the Bay Bridge. It then went to Mojave, and without any difficulty traveled over the old borax road to Harmony Borax Works. In 1940 it crossed the country to publicize the movie "Twenty Mule Team", starring Wallace Beery. Then, in 1949, it participated in the centennial pageant staged in Death Valley by the Death Valley 49ers. Ironically, the twenty-mule teams, perhaps our most enduring symbol of Death Valley, did not achieve national attention until long after the last Death Valley run was completed. It was the long service they rendered hauling borax from Borate to Daggett that defined this American institution. Although Death Valley and Mojave are most commonly associated with the famous outfits, the Borate-Daggett run is where their greatest fame and accomplishments were achieved.

During its heyday, as more and more mining came to the desert, the increasing rail traffic prompted a desire by the Santa Fe to expand Daggett into a huge rail yard. Supposedly, property owners wanted so much for the land that the railroad built their yard arid roundhouse a few miles west at Barstow, which was named after railroad superintendent William Barstow Strong. That city today remains a major rail yard and junction point for both the Burlington Northern-Santa Fe and the Union Pacific.

The Alf family is one of the pioneer families of this region. Seymour Alf moved to Point of Rocks (Helendale) in 1881. After trying his hand at farming he bought land and moved to the Fish Ponds area. Here he went into the business of freighting and raising cattle to supply the local miners with beef. In 1885 he moved to Daggett, where he built a large blacksmith shop and expanded into the business of road building and grading. He is perhaps most noted for constructing the twenty-mule team wagons, of which we have previously heard.

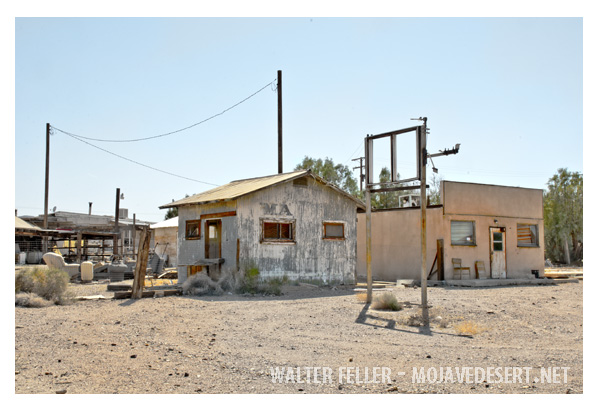

Seymour Alf died in 1922, and his son Walter carried on the business until his death in 1970. The blacksmith shop still stands and remains in the Alf family.

Another Daggett landmark is the Stone Hotel on Santa Fe Street. It was originally built as a two-story building, but in 1908, after surviving three fires, it was rebuilt with only one floor. During its career it hosted such luminaries as Death Valley Scotty, Borax Smith, Lt. Gov. John Daggett, and John Muir. Muir's daughter kept a home a short distance east of town which still stands today.

A building which elicits great curiosity from sightseers is the so-called Ski Lodge House, located just a short distance south of the tracks in Daggett. Its unique roof line is instantly recognizable by anyone who has ever viewed it. It was built in the 1920s by the Minneola Land Development Company as a sales office to attract attention and entice potential buyers to drop in. At this time the Daggett Ditch, or Minneola Canal, was being expanded eastward in an attempt to open up more of the desert to cultivation. The area was touted as another Coachella Valley, with a great future as an agricultural center. This potential was never realized, and the remnants of many ditches and canals remain today. The house has been used over the years for various purposes, including gas stations and cafes. It is under private ownership today.

The focus of Billy Holcomb Chapter's Spring Clampout is what is now known as the Daggett Garage or the Fouts building. It began its life in the 1880s as a repair building at the roundhouse for the narrow-gauge Borate and Daggett Railroad, repairing and maintaining the small "pufferbell" locomotives that hauled the borax. In about 1896, Seymour Alf used a 20-mule team to move the building to the Waterloo Mine in the Calico Mountains, where it served a similar purpose for a narrow-gauge rail line hauling silver ore. Walter Alf, Seymour Alf's son, moved it to its present location around 1912. Over the years it served many other purposes, including stints as a livery stable and a grocery store.

It then became an auto repair shop on the National Old Trails Highway, later Route 66, until World War II, when it was reincarnated as a mess hall for soldiers guarding the local railroad bridges. It was purchased by the Fouts brothers, locally known as “the cussing brothers” for their speech habits, in 1946.

They operated it as an auto garage and machine shop until the mid-1980s. It is currently owned and operated by the Golden Mining and Trucking Company.

Although one would hardly know it today, Daggett was once a booming railroad, ranching, and mining community that was the main settlement in this part of the desert. It was to Daggett that one came for supplies and services, and to blow off some steam on a Saturday night. Until the completion of Interstate 40 in the mid-1970s it was traversed by a major east-west national highway as well as the main line of the Santa Fe Railroad. Old Route 66 is gone forever, and the Santa Fe is now the Burlington Northern-Santa Pe, but Daggett continues as a viable, albeit small, community rich in tradition and worthy of attention by anyone interested in the history of the western Mojave Desert.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hensher, Alan, Ghost Towns of the Mojave Desert. California Classics Books, Los Angeles, 1991.

Leadabrand, Russ, A guidebook to the Mojave Desert of California. Ward Ritchie Press, Los Angeles, 1966.

Lingenfelter, Richard, Death Valley and the Amargosa. University of California Press, Los Angeles, 1986.

Mann, William Jack “Shortfuse", Guide to the Calicos: Ghost Mining Gamps and Scenic Areas. Vol. H. Shortfuse Publishing Company, Barstow, 2000.

Miller, Ron* and Peggy, Mines of the Mojave. La Siesta Press, Glendale, 1976.

Weight, Harold O., 20-Mule Team Days in Death Valley. The Calico Press, Twentynine Palms, 1955.

*Former Noble Grand Humbug of Billy Holcomb Chapter 1069, now gone to the Golden Hills.

THE ANCIENT AND HONORABLE ORDER OF

E CLAMPUS VITUS

BILLY HOLCOMB CHAPTER 1069

HISTORIC DAGGETT GARAGE

Written by MIKE JOHNSON, XNGH, CP.

Shorty Harris & Death Valley Scotty

Pioneers washed their underwear

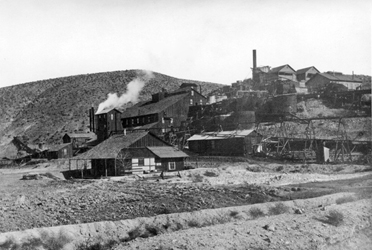

Daggett Mill

Calico 2000

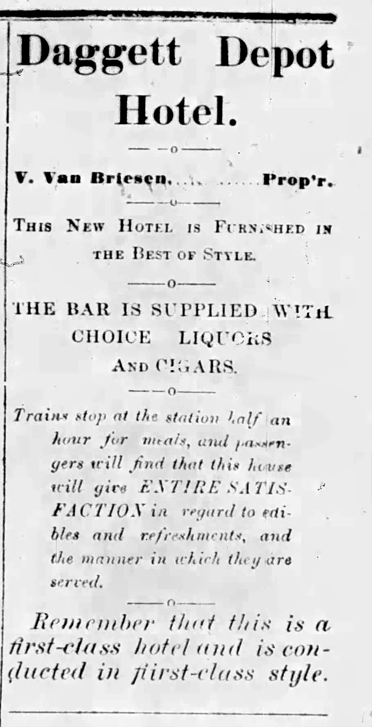

Daggett Depot Hotel ad - 1885