Death Valley's Lost 49ers

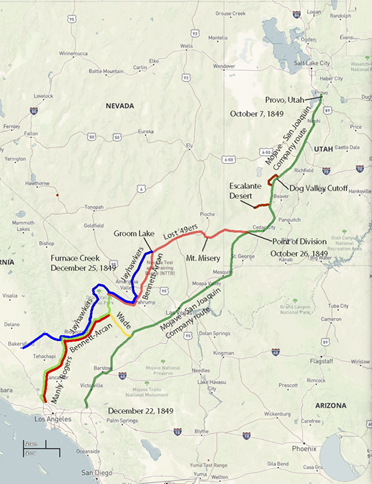

In January of 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in California and people from all over the United States packed their

belongings and began to travel by wagon to what they hoped would be new and better life. Since most of these

pioneers began their exodus to California in 1849, they are generally referred to as 49ers. One of the supply

points along the trail was Salt Lake City, where pioneers prepared for the long journey across the

Great Basin desert before climbing over the

High Sierra Mountains

to the gold fields of California. It was important to leave

Salt Lake City and cross the desert before snow began to fall on the Sierra Mountains, making them impassible.

Only a couple of years before, a group of pioneers called the Donnor Party left late out of Salt Lake City

and was trapped by a storm, an event that became one of the greatest human disasters of that day and age.

The stories of the Donnor Party were still fresh on everyone's mind when a group of wagons arrived at

Salt Lake City in October of 1849. This was much too late to try to cross the mountains safely, and it looked

like these wagons were going to have to wait out the winter in Salt Lake City. It was then that they heard

about the

Old Spanish Trail,

a route that went around the south end of the Sierras and was safe to travel

in the winter. The only problems were that no pioneer wagon trains had ever tried to follow it and they could

only find one person in town who knew the route and would agree to lead them. As this wagon train left

Salt Lake City, some of these people would become part of a story of human suffering in a place they

named

Death Valley.

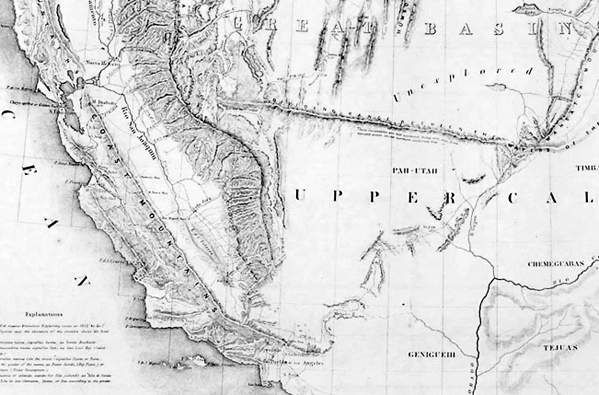

The first two weeks of travel on the

Old Spanish Trail

were easy, but the going was slower than most

of the travelers wanted. The leader of the group,

Captain Jefferson Hunt,

would only go as fast as the

slowest wagon in the group. Just as the people were about to voice their dissent, a young man rode into camp

and showed some of the people a map made by

John Fremont

on one of his exploratory trips through the area.

The map showed a short cut across the desert to a place called

Walker Pass. Everyone agreed that this would cut

off 500 miles from their journey so most of the 120 wagons decided to follow this map while the other wagons

continued along the Old Spanish Trail with Captain Hunt.

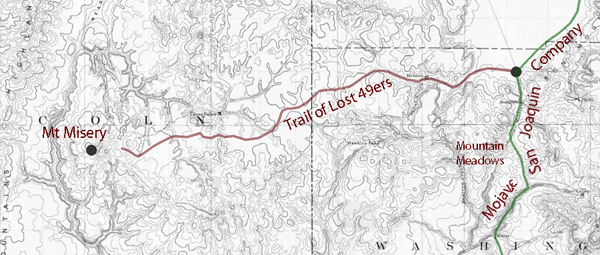

The point where these wagons left the Old Spanish Trail

is near the present day town of Enterprise, Utah where a monument (Jefferson Hunt Monument) has been constructed

to commemorate this historic event. Almost as soon as these people began their journey, they found themselves

confronted with the precipitous obstacle of Beaver Dam Wash, a gaping canyon on the present day Utah-Nevada state

line (Beaver Dam State Park, Nevada). Most of the people became discouraged and turned back to join

Jefferson Hunt,

but about 20 wagons decided to continue on. It was a tedious chore getting the wagons across

the canyon and took several days. In the mean time, the young man who had the map of the short cut got

impatient and, under the cloak of darkness, left the group. Despite the fact that the group didn't have a map,

they decided to continue on thinking that all they had to do was go west and they would eventually find the pass.

After crossing Beaver Dam Wash the group passed through the area of present day Panaca, Nevada and crossed

over "Bennett's Pass" to Del Mar Valley. Here they started having difficulty finding water but eventually found

their way to Crystal Springs in the Paranagat Valley. They continued over Hancock Summit into Tikaboo Valley

and then on to Groom Lake in central Nevada. They had now been slowly making their way across the desert for

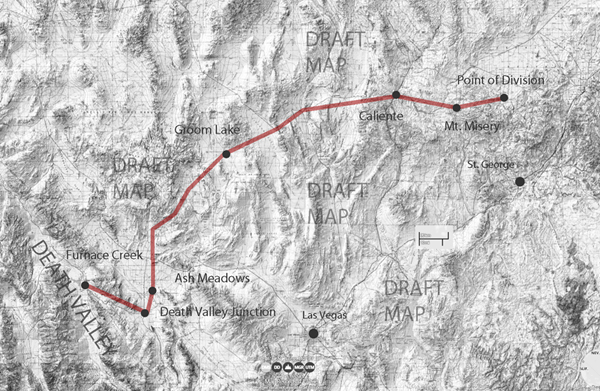

almost a month since they had left the Old Spanish Trail . At Groom Lake they got into a dispute on which way

to go. One group wanted to follow a well traveled Indian trail to the south in hopes of finding a good water

source. The other group wanted to stay with the original plan of traveling west. The group eventually split

and went their separate ways but they both were to have two things in common. They were both saved from dying

of thirst by a snow storm and they both ended up meeting again in a place called

Ash Meadows

located east of Death Valley. From here they continued on through present day

Death Valley Junction

and along the same route followed by

Highway 190. On Christmas Eve of 1849, the group arrived at Travertine Springs,

located about a mile from

Furnace Creek.

The lost pioneers had now been traveling across the desert for about two months since leaving the Old Spanish Trail.

Their oxen were weak from lack of forage and their wagons were battered and in poor shape. They too were weary

and discouraged but their worst problem was not the valley that lay before them. It was the towering mountains

that stood like an impenetrable wall as far as could be seen in both directions.

They decided to head toward what appeared to be a pass to the north near present day Stovepipe Wells, but after

discovering this was also impassible, decided they were going to have to leave their wagons and belongings

behind and walk to civilization. They slaughtered several oxen and used the wood of their wagons to cook the meat

and make jerky. The place where they did this is today referred to as "Burned Wagons Camp" and is located near the

sand dunes

of Death Valley. From here, they began climbing toward Towne Pass and then turned south over Emigrant Pass to

Wildrose Canyon. After crossing the mountains and dropping down into

Panamint Valley,

they turned south and climbed a small pass into Searles Lake Valley before making their way into

Indian Wells Valley near the present day city of

Ridgecrest.

It was here that they finally got their first look at the Sierra Mountains. They turned south, probably following a

trail and traveled close to the same route followed by Highway 14. Ironically, they walked right by Walker Pass

(Highway 178

to Isabella Lake), the place they had set out to look for almost three months earlier.

From Walker Pass,

they entered into what was to become the worst part of their journey, the

Mojave Desert Plateau.

This is a flat, featureless land with very few water sources to be found. The only things that saved them from

dying of thirst were a few puddles of water and ice from a recent storm. Eventually they found their way over a

pass near

Palmdale, California

and, following the Santa Clarita River drainage, were finally discovered and rescued by Spanish cowboys from

Rancho San Fernando, located near present day Newhall, California.

Source - NPS

Death Valley in '49

William Lewis Manly

Monument at Bennett's Long Camp

Naming of Death Valley

...

Just as we were ready to leave and return to camp we took off our hats, and then overlooking the scene of so much trial, suffering and death spoke the thought uppermost saying:--"_Good bye Death Valley!"_ then faced away and made our steps toward camp. Even after this in speaking of this long and narrow valley over which we had crossed into its nearly central part, and on the edge of which the lone camp was made, for so many days, it was called Death Valley.

View toward Death Valley from the top of Walker Pass

"Ironically, they walked right by Walker Pass ..."

Manly and Rogers had to descend through the El Paso Mountains. Many believe they came through Last Chance Canyon to do so.