Beatty Beginnings

Of all the communities established in the Bullfrog area, Beatty had the best location. The site was relatively flat, and water could be obtained from wells drilled in the center of town at depths of less than 30 feet (Weight, 1972:14). But the promotion, in spring 1905, of the new nearby townsite of Rhyolite, just west of the Montgomery Shoshone Mine, drew settlers from adjoining communities. The location of Rhyolite was a beautiful site for a town-a lovely desert valley surrounded on three sides by ridges of the bullfrog Hills, open to the south, offering a wonderful view of the Funeral Mountains and the north end of the Amargosa Valley. Ladd Mountain was the high point on the east margin of the bowl in which Rhyolite sat; Sutherland Mountain was on the west; and Busch Peak was on the north. Rhyolite was high enough in the hills to be relatively cool in the summer, yet far enough south to experience mild winters. The valley was wide enough to accommodate a good-sized town, but the site had two drawbacks. It was a long way to water in any direction, and because the site was in a bowl, open only on one end, it was not as accessible as Beatty.Bob Montgomery Founds Beatty

If Bob Montgomery had not bought into the Beatty Town-ship, it, too, might have become depopulated by the early exodus to Rhyolite. Montgomery's vow to build a grand hotel and make the town a milling center persuaded many Beatty residents not to join in the rush to Rhyolite (Lingenfelter, 1986:209). The town of Beatty was probably laid out in 1904 or 1905. Montgomery filed the first plat map of the community, which contains the names of Beatty's first streets. The post office was established January 19, 1905 (Carlson, 1974:48). Montgomery himself hosted Beatty's first Thanksgiving dinner in a small tent on Main and Second Street in November 1904. Matt Hovek, Judge Sexton, J. R. McDonald, and Charles Watson were among the guests. The menu included bean soup, boiled beans and bacon, baked bacon and beans, desert flapjacks, and coffee (Weight, 1972:16).Montgomery kept his promise to build a hotel in Beatty, and its construction probably played no small part in the consolidation of Beatty as a community. At a cost of $25,000, the hotel was the largest in the district at that time-indeed, one of the finest hotels in Nevada south of Reno. The grand opening of the Montgomery Hotel took place on October 25, 1905, with guests from as far away as Tonopah. A grand march was held, led by Mrs. Montgomery (who had come from San Francisco for the event) and Malcolm MacDonald, a Tonopah mining engineer and partner of Montgomery. Several weeks later Thanksgiving dinner was served at the establishment. The feast, elaborate by any standards (but especially in comparison to Montgomery's 1904 menu), included, among many other items, bluepoint oysters, chicken soup, Amargosa trout, lobster salad, potato salad, boiled chicken, calves' brains, roast young turkey, suckling pig, olives, pickles, green corn, stewed tomatoes, hot mince pie, pumpkin pie, New England plum pudding, hard and brandy sauce, nuts, cheese, Manhattan cocktails, a selection of wines, and cafe noir (Weight, 1972:16). (In 1909 the Montgomery Hotel was dismantled, moved to Pioneer, and renamed the Holland House; it later burned to the ground [Lingenfelter, 1986:231].)

In February 1906 (less than two years after he filed Beatty's plat map), Montgomery sold part of his Beatty interests, including the Montgomery Hotel, to Charles Schwab. But Schwab had no real interest in the Beatty holdings he had purchased from Montgomery, and shortly after the arrival of the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad, he sold them to Dr. William S. Phillips for a reported $100,000. Phillips, a con man known as the "little millionaire hustler from Chicago," proudly announced his plan to make Beatty the "Chicago of Nevada." When Beatty's second railroad, the bullfrog Goldfield, arrived in 1907, Phillips flamboyantly revealed his design to build a $100,000 hotel, a hospital, a city hall, a church, and so forth. He placed signs on vacant lots around the town where he planned to construct these buildings. He sold as many lots as he could, then skipped town (Lingenfelter, 1986:229).

Bob Montgomery was thus the father of Beatty; and de-spite Schwab's lack of support for the town and Phillips' exploitative activities, the town survived its first years and was on its way to permanence on the Nevada map.

Newspapers in the bullfrog District

The newspaper editor was usually an early arrival in a boom camp-not far behind the prospectors, boomers filing claims, saloon keepers, and good-time women. The local newspaper served as both a source of news as well as a self-appointed community booster, tirelessly extolling the virtues and bright future of the new camp. But the spirit of competition that infected early arrivals to the Bullfrog mining district for the most propitious sites to stake claims and build communities also engulfed the editors of the district's first two news-papers. A robust controversy quickly developed over who was entitled to use the name bullfrog Miner. In early March 1905, C. W. Nicklin put out a sample edition of a paper called the bullfrog Miner and mailed it to prospective subscribers (Lingenfelter and Gash, 1984:25). A few weeks later, he arrived in Beatty with press and materials, and on April 8 published the first regular edition. (Nicklin was "Johnny on the spot" when it came to starting a newspaper in a new town. On April 7, 1905, he started the Las Vegas Age, the third paper to start publication in Las Vegas within two weeks in anticipation that a bustling frontier community would spring up in the Las Vegas Valley and serve as a midway point on Senator William A. Clark's San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad and as a supply center for the new mining towns to the north [Roske, 1986:1441].) On March 31, 1905, Frank P. Mannix, at the urging of the Bullfrog Townsite Company, began publication in Bullfrog of a paper also named the bullfrog Miner. Incessant quarreling followed over who had the rights to the catchy name. The word Bullfrog, of course, was magic in the district and both insisted on using it. There was also a superstition in the majority of western mining camps that working men would not accept a newspaper that did not have the word "miner" in the title (Lingenfelter and Gash, 1984:25). The quarrel continued until May when Nicklin renamed his paper the Beatty bullfrog Miner.The Beatty bullfrog Miner changed hands several times; in May 1909, with Nicklin once again the owner, it was sold to Earle R. Clemens, owner of the Rhyolite Herald. Clyde R. Terrell was owner or co-owner of the Beatty bullfrog Miner between 1907 and 1909. Clemens folded the Beatty bullfrog Miner in July 1909 (Lingenfelter and Gash, 1984:16).

When the town of Bullfrog lost out in competition with Rhyolite for population, Mannix moved the bullfrog Miner to Rhyolite in spring 1906, where it was published in competition with the Rhyolite Herald until September 25, 1909, and then sold to the Herald (Lingenfelter and Gash, 1984:25, 218).

The most important paper in the Rhyolite district was the Rhyolite Herald, which began publication May 5, 1905, under the editorship of Earle R. Clemens. The Herald achieved a circulation of 10,000 by 1909 and was available on newsstands in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Salt Lake City, San Antonio, Omaha, Chicago, and New York. Clemens sold the paper in April 1911 and it ceased publication June 22, 1912 (Lingenfelter and Gash, 1984:16).

It would be nearly 35 years before the Beatty area would have another newspaper. On April 25, 1947, Robert A. Crandall began publishing a supplement to the Goldfield News, titled the Beatty Bulletin. It provided local news and was published until December 28, 1956, when the Goldfield News and Tonopah Times-Bonanza were merged (Lingenfelter and Gash, 1984:16).

Hauling Freight: Before the Railroads

The bullfrog mining district was located in the middle of a vast little-explored wilderness, one of the most remote and inaccessible areas in the American West. Goldfield, the closest community of any consequence, was 65 miles to the north; Tonopah was about 90 miles away. Barren desert valleys separated by rugged mountain ranges lay to the east and west. One hundred and twenty miles of wilderness to the east separated Beatty and Pioche. To the west lay the Death Valley sink. More than 110 miles to the southeast was the Las Vegas Valley, where, like Beatty and Rhyolite, a new community called Las Vegas was beginning to develop. It was the beginning of the twentieth century, but as far as transportation and communication were concerned, it could have been the west 25 or even 50 years earlier. Until the railroads arrived in the Bullfrog district in late 1906, the only way to get in or out of the area was by horsepower or on foot, north to Goldfield or south to Las Vegas.By the time Senator Clark's San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake (SP, LA, & SL) Railroad was completed in 1905, a rag town had developed on 80 acres of land located just north from Las Vegas's present downtown, which Canadian-born John T. Williams had purchased from Helen Stewart. On May 15,1905, the railroad auctioned off subdivided lots at the Clark Townsite, located on either side of Fremont Street between Main and Fifth (Roske, 1986:55- 56). The boom at Bullfrog and Rhyolite had provided an immediate spur to the Las Vegas economy, but not everyone who tried to make a success of a business venture made a profit. With the arrival of the railroad, many businesses engaged in forwarding freight delivered to Las Vegas on the railroad for shipment by wagon north prospered. By early June 1905, nearly 1500 horses were engaged in hauling freight from Las Vegas to Bullfrog, and 50 freighters would daily pass each other on the road (Paher, 1971:87).

Teams of 6, 12, 16, and 20 horses or mules were used. The large ensembles were driven with a "jerk line"-a single line attached to the lead animal. Roads were little more than a deep wagon track filled with a fine dust. A speedy rate of travel was 2 miles per hour. As they traveled, wagons and horses produced clouds of dust. A thick cast of dust formed on the faces of the drivers. At night, when the camp was made, the driver had to unhitch the team, feed and water the hungry animals, and dine on bread fried in bacon grease. At night he might be awakened several times by the unruly animals getting tangled up in the ropes. The next morning it was necessary to feed and water the animals, harness them, and once more begin a long day.

Though the opportunities for freighting goods and supplies north were ample, the business was not for beginners. William Thomas Stewart was one who tried and profited. Stewart, a Mormon, was born in Utah and had spent time in Delamar, the turn-of-the-century mining camp located southwest of Pioche in Lincoln County. Following the fading of Delamar, Stewart's family purchased a ranch in the Pahranagat Valley. Stewart's wife, however, did not like the unsettled character of the valley; she preferred Las Vegas, where she and her husband moved. Stewart, who was then employed as a carpenter, was highly skilled in working with horses. He jumped at the opportunity to purchase a six-horse team (known as a three-span) and two wagons owned by a Las Vegas physician who used the outfit to haul freight between Las Vegas and the Bullfrog district. The physician, like many in the freighting business at that time, had only limited understanding of horses and the subtleties of the freighting enterprise. Among other things, he was unable to hire teamsters, known as "skinners," who could or would "lay off the bottle," and he did not know the tricks of feeding and handling horses and loading wagons. As a result, the physician was losing money on the enterprise and offered to sell the three-span and two wagons to Stewart. Stewart purchased the outfit and immediately set about putting it on a paying basis.

The first thing Stewart did was to begin feeding the horses properly-plenty of oats along with their hay. With the improved diet, the horses put on weight and had more energy. When he purchased them the horses had sores on their skin caused by the rubbing of ill-fitting collars and harnesses. Stewart treated the sores with ointment. He adjusted each horse's collar and harness so it fit properly and would not irritate the horse on the long drive. Moreover, he put the horses on a training program. Some of the horses (like some people) would not work hard without proper treatment and "incentives." The commands he gave the horses were always in a calm, firm voice. Stewart's son Dan, who ran cattle most of his life in the Groom Lake area and was also skilled in handling horses, states, "I've seen fellows that were balky drivers. They made their horses balky because they scream and holler at them, let them lunge and carry on. But my father, he knew how to handle livestock-he knew how to handle horses. He'd speak in a calm, gentle voice and just tell them to go" (Stewart, 1991).

Stewart's method for determining which horses were working and which were not was to hook them to a loaded wagon, set the brake, and speak to them in a calm and gentle voice, telling them to "move out." The horses that were working would "step right in and take hold," Stewart says. It was then obvious which horses were not pulling. Stewart would then say, "Whoa." If "one of them didn't get in and do his part," Stewart would step down off the wagon and "train him up with a halter chain"-whip them lightly on the ribs. A couple of sessions of that and "all he had to do was rattle the halter chain" (Stewart, 1991). In a short time, Stewart had his horses so well-fed and trained that the three-span was pulling 3000 pounds of freight per horse in the two wagons, an unusually large amount, on the Las Vegas-Bullfrog route. What is more, Stewart traveled alone. He had the same wagons, same horses, and same road conditions, but he made money where many others could not. The difference was in "the man on the seat," son Dan states (Stewart, 1991).

The trip to bullfrog from Las Vegas took a week and Stewart could earn as much as $600 per round trip if every-thing went well. After leaving Las Vegas, he camped the first night at Tule Springs at the north end of the Las Vegas Valley; the second night was spent at Indian Springs. Water was available at both camps. The third night was spent at a dry camp between Indian Springs and Ash Meadows. The fourth night was at wet camp at Ash Meadows. The trip into Beatty took another two or three days; all those nights were spent at dry camps (Paher, 1971:95). He hauled groceries, mining equipment, and anything else that was needed in the boom camps. The freight, of course, came to Las Vegas on the railroad. Hay and grain were dropped off at all camps on the way north for use on the return to Las Vegas. A barrel of water was also deposited at dry camps for use on the way back. A teamster had little worry about the safety of feed and water-stealing a freighter's provisions could bring the death penalty to the thief on the Nevada desert.

The freighting to Bullfrog from Las Vegas by Stewart and the other skinners did not last long. At the end of December 1905 the first Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad (LV&T) locomotive was delivered in Las Vegas for use in the first construction train on the railroad (Myrick, 1963:463). By March 1906 a train ran from Las Vegas to Indian Springs (Myrick, 1963:466), with full, regular service reaching Gold Center in October of that year (Myrick, 1963:475). As the railroad tracks moved north from Las Vegas, opportunities for freighters on the Las VegasBullfrog route quickly evaporated in the face of com-petition from the iron horse. Following the establishment by the railroad of an autopassenger line between Las Vegas and bullfrog, and completion of the Armor and Company ice and cold storage plant in Las Vegas in August 1905, meats, fruits and other perishables, in small quantities, were available in the bullfrog district on a daily basis-although at a premium price (Paher, 1971:96).

Prudent person that he was, Stewart saved the profits he made from freighting and moved to the family ranch at Alamo, in the Pahranagat Valley. His wife was now willing to live there because it had become a little more developed while the family had been in Las Vegas. Interestingly, Stewart kept his wagons and horses upon returning to the Pahranagat Valley, and during World War I used them to haul rich lead ore from the Groom Mine on Bald Mountain in Lincoln County to the LV&T railhead at Indian Springs (Stewart, 1991).

The Railroads Reach Beatty

Of the three railroads that eventually connected in Beatty, the first to arrive was Senator William A. Clark's Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad (LV&T). Clark had constructed the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad (SP, LA, & SL) through Las Vegas, completing it in January 1905 (Myrick, 1963:455). Borax Smith planned a railroad that would connect Las Vegas with Tonopah, tying into Clark's railroad at Las Vegas (Myrick, 1963:461). When Clark refused to let Smith connect with his SP, LA, & SL, Smith abandoned plans for a Las Vegas destination and moved to Ludlow, California, where his Tonopah and Tidewater (T&T) line could connect with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe. In October 1905 Clark purchased Smith's terminal site in Las Vegas along with 9 miles of completed grade to the north (Myrick, 1963:461). On Friday, October 12, 1906, the first regular passenger train made its run from Las Vegas to Gold Center, located about 5 miles south of Beatty, just beyond the Beatty Narrows (Myrick, 1963:475).Fully scheduled service from Las Vegas to Beatty began on October 22, 1906, and Beatty celebrated by officially designating October 22 and 23 as Railroad Days. A delegation of local boosters traveled from Beatty to Las Vegas to meet special trains of celebrants from Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. The two special trains were combined into one, consisting of eleven Pullmans, a day coach, a diner, and two special cars of visiting dignitaries. Slowed by a breakdown on the desert, the delegation arrived in Beatty at 8:30 P.M. on October 22 (Myrick, 1963:475). The town was draped with festive bunting for the occasion, and visitors gathered at the Montgomery Hotel. After the celebration was over, one guest stated that the Railroad Days celebration "marked the camp's emancipation from the slavery of the desert" (Myrick, 1963:478).

The Beatty depot of the LV&T was located at the south-eastern edge of town between Second Street and Third Street. The line's boardinghouse was constructed along the tracks to the north near the end of Second Street. The LV&T passed through Beatty to the north, circling first to Rhyolite, then on to Goldfield (Myrick, 1963:471). It ceased operations after twelve years, in October 1918 (Myrick, 1963:502).

The second railroad to reach Beatty was the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad (BG), which arrived April 25, 1907 (Weight, 1972:17). It was financed by a syndicate that involved many prominent Philadelphians, including John Brock who had major mining holdings in Tonopah and had been behind construction of the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad (Myrick, 1962:259; 1963:507). At Goldfield it connected with the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad, which ran on to Tonopah (Myrick, 1963:505). South of Goldfield, stations included Keith, Stella, Cuprite, Wagner, San Carlos, Bonnie Claire, Jacksonville, Ancram, Springdale, Hot Springs, and Beatty (Myrick, 1963:505). The BG traveled south through Beatty, passed through the Beatty Narrows, and circled round the south end of the bullfrog Hills to Rhyolite. After 1914, the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad used the Las Vegas and Tonopah tracks from a point just south of Bonnie Claire to Goldfield, with the other tracks between Rhyolite and Goldfield being abandoned (Myrick, 1963:505).

The BG's arrival offered Beatty's citizens another opportunity for a celebration. A headline in the Beatty bullfrog Miner read, "Railroad Day Beat Any Fourth of July We Ever Had." Excursion trains arrived from Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Tonopah, and Goldfield. Old Man Beatty drove the symbolic golden spike uniting the rails, and more than 700 people banqueted in the Miners' Union Hall in Rhyolite (Weight, 1972:17). Although the bullfrog Goldfield was a separate entity, it was dominated by the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad. The BG lasted until January 1928, when its last train departed from Beatty (Myrick, 1963:536). Because it duplicated service provided by the LV&T, Myrick (1963:505) called it, "Without a doubt, . . . Nevada's most unwanted railroad."

Borax Smith's Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad reached Beatty on October 27, 1907 (Carlson, 1974:48). Technically the T&T Railroad did not go into Beatty but went only as far as Gold Center; it then used the bullfrog Goldfield's railroad tracks to travel on through the Beatty Narrows and into Beatty. All operations on the T&T ceased on June 14, 1940 (Myrick, 1963:593). On the fate of the T&T's materials, Myrick wrote:

On July 18, 1942, contractors Sharp and Fellows began tearing up the rails at Beatty and, working southward, the job was completed all the way to Ludlow by July 25, 1943. Of the residue, a quantity of bridge timbers ended up as part of the Apple Valley Inn at Apple Valley, while the ties became scattered all over, a large number being used in the building of the El Rancho Motel in Barstow. Two of the locomotives went to the Kaiser Steel Plant at Fontana, California, while a third went to the San Bernardino Air Base (Myrick, 1963:593). Some old-timers in Beatty report that a T&T locomotive is buried under about 5 feet of dirt under Highway 95 just north of Beatty. In 1957 it was mired in the mud and crews upgrading the highway were in a hurry and simply covered it over with dirt rather than try to move it (Reidhead, 1987).

The Last Years of Old Man Beatty

Toward the end of his life-when he was more than 70 years old and when Beatty was just being platted, Old Man Beatty became the first postmaster in the town that bore his name. He was appointed despite the fact that he could not read and could write only his name, which he did with great care and in full. He assumed the post on January 19, 1905, and resigned March 24, 1906 (Weight, 1972:14-16). Two years later at the age of 73, Old Man Beatty died of a fall from a wagon while hauling wood from Bare Mountain. An editorial in the Rhyolite Herald eulogized him under the headline "The Last of the Squaw Men":Unlike many white men who lived with squaw wives, Old Man Beatty did not desert his companion when the country began to settle up. When fortune favored him, he gave his family all the comforts his fortune could afford. Whatever may have been the faults of this hearty pioneer, his devotion to his squaw and children evidenced a manly virtue. There is a genuine feeling of regret and a deep sense of loss among the oldtimers in the Bullfrog district over the death of this old man, whose cabin was a sheltering place for many a weary traveler in the early days, and whose hospitality was extended to the poor and rich alike (Weight, 1972:17).

Judge William Gray: Long-time Resident

Although many early residents of Beatty stayed for only short periods of time, one- Judge William Gray-was a resident from the time the town was founded until the World War II years. He made many contributions to the area. Judge Gray served for many years as the community's Justice of the Peace and also as land commissioner of the district. He helped build the church next door to his home in Beatty, and along with Walter Bond, constructed a road across Timber Mountain into Fortymile Canyon, now located on the Nevada Test Site. He helped secure Fortymile Canyon by locating placer claims along its bottom until Governor James G. Scrugham persuaded the Nevada legislature to set it aside as a state preserve. Fortymile Canyon was said to have been a "library of Indian writings." Gray also held mining claims in Skidoo (Lee, 1932:113).Judge Gray was in Goldfield when the news of the Bull-frog discovery led to outlandish tales. He was initially impressed by the "boomers' promotional activities in Goldfield and traveled south to see for himself. He was more than a little disappointed. "The boomers didn't care how much they told the truth," one old-timer later said. Boomers had put a display in a store window in Goldfield, featuring a chunk of gold as big as man's fist that was said to have been from the Kismet Mine high on Bare Mountain; next to it was a big trout. A sign in the window read: "Come to Gold Center. Find mines with ore like this. Catch trout like this one in the Amargosa River." In Goldfield, boomers showed Gray lithographs of the Amargosa River with boats on it. In the pictures, the river's banks were lined with trees and cattle grazed in lush green pastures. In contrast old-timers in Beatty often swore that they had seen fish in the Amargosa River carrying patched canteens (Lee, 1932:114).

J. Irving Crowell and the Chloride Cliff Mine

J. Irving Crowell arrived in Beatty in 1905 after a three-day trip by horse and buggy from Las Vegas. He was originally from New England and had been raised on Cape Cod. His wife, Annie, a Canadian, remained in the couple's home in Los Angeles while Crowell was on the desert seeking his fortune as a mining promoter (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).The Chloride Cliff. Mine, located near the crest of the Funeral Mountains almost due west of Beatty and south of Daylight Pass, was an old mine; it had originally been discovered by August J. Franklin, a man named Hanson, and Beatty pioneer Eugene Lander in August 1871. The company Franklin and his partners formed was disbanded, but Franklin continued to hold the property until his death in 1904, when his son George took it over. Activity at the nearby Keane Wonder Mine led to revived interest in the immediate area, and prior to the Panic of 1907, J. Irving Crowell purchased an interest in the Chloride Cliff Mine from George Franklin for an estimated $110,000 (Lingenfelter, 1986:136).

After his initial purchase, Crowell obtained backing from investors in Pennsylvania and reopened the mine under the banner of the Penn Mining and Leasing Company in the fall of 1909. Crowell found gold-bearing rock assaying at better than $35 a ton and constructed a 1- stamp mill at the foot of the mine dump. Some ore was shipped, and at one point Crowell attempted unsuccessfully to sell his holdings to investors in England (Lingenfelter, 1986:304- 305). Crowell maintained a residence on the property until 1917 (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987). Crowell's son, J. Irving Crowell, Jr., said that his father never made a lot of money on the Chloride Cliff Mine but that some leasers did fairly well (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

J. Irving, Jr., was born in Los Angeles in 1900. He attended public schools in Los Angeles, and as a youth spent his summers with his father at Chloride Cliff. Young Crowell first came to Rhyolite in 1910 and stayed at the Southern Hotel, where he had his first taste of champagne. Crowell, Jr., re-called little activity in Beatty during this period; most of the action was in Rhyolite. "In 1917," Crowell said, "Beatty was a shell of what it is now." He remembered traveling to Gold Center with his father around 1912 to look at a mill. Rather than walk back to Beatty they flagged down the LV&T by standing in the middle of the tracks and waving their shirts. The engineer acknowledged them by blowing his whistle twice, slowed down, and stopped in front of them (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

The Chloride Cliff Mine was 18 miles from Rhyolite; the trip took 5 hours by horse and buggy. Sometimes young Crowell would accompany his father into Rhyolite for supplies, and the father and son would spend the night in Rhyolite and return the next day. Al McPherson, a teamster in Beatty, often hauled supplies from Rhyolite out to the Chloride Cliff.. Crowell had no phone at his place, but there was one at the nearby Keane Wonder Mine. Sometimes the elder Crowell would walk to the Keane Wonder and call an order in to McPherson, who would then bring it out (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

The Crowells' Fluorspar Mine

In 1917 a man named Bill Kennedy was prospecting on Bare Mountain. He threw down his pick and broke loose a piece of soft, purple rock. The next day he happened to meet J. I. Crowell and showed him a specimen. Crowell recognized the sample as fluorspar (calcium fluoride), and he purchased the information on the formation's location for $500 cash. Following Kennedy's directions, Crowell went to the site, staked out a claim, and filed a location notice. He named his new claim the Daisy. Over the years several other claims were added to what is now sometimes referred to as the Daisy Group (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987). Originally Crowell's interest in the Daisy focused on gold prospects rather than fluorspar, the presence of which was believed to be a favorable indication that gold-bearing ore existed at lower levels. Fluorspar was much less glamorous than gold and was used primarily as a catalyst in the production of steel; it has the effect of making molten slag thinner and more fluid. Although Crowell never found gold at his fluorspar mine, the property has proven to be a solid producer of fluorspar; it was the longest continuously operated mine in the Beatty-Death Valley area (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).Shortly after filing on his fluorspar claim, Crowell moved from Chloride Cliff. to Beatty. Louis Vidano, who had worked with Crowell at the Chloride Cliff Mine for several years, accompanied him to his new mining property on Bare Mountain. They began sinking a shaft in the fluorspar; the material was so soft that holes for blasting could be drilled with a hand auger. A headframe was built, and ore was hoisted with a 15-horsepower Fairbanks-Morse torchignited engine. Crowell worked the mine steadily until 1923, at which time the shaft was 134 feet deep. In the early 1920s Crowell attempted to concentrate the fluorspar ore in a mill constructed behind his home in Beatty. The fluorspar was originally run over gravity tables; later a flotation process was used. The efforts did not last long, however, and no milling has been done at the site since. Instead, the ore was hand sorted to remove the waste rock. The fluorspar ore shipped from the mine was known as 85/5 ore, meaning it contained a minimum of 85 percent calcium fluoride and less than 5 percent silica (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

In 1923, personal misfortune struck Crowell. For years he made regular visits to his wife and family in Los Angeles by boarding a Pullman in Beatty and traveling down the T&T to Ludlow, where the car was transferred to the Santa Fe Railroad tracks for the ride to Los Angeles. On one fateful trip, when the Pullman was transferred to the Santa Fe the train did not hook properly onto the Pullman, and the car came loose. The Santa Fe train backed up to connect the Pullman, which by this time stood motionless on the tracks. The engineer misjudged the distance between the train and the stray car and rammed the Pullman at 35 miles an hour. Crowell was thrown head-first through a partition and was severely injured. He was an invalid for months. He partially recovered, but never was able to do physical labor again. Because of his injuries, Crowell was forced to close the fluorspar mine temporarily, and the fate of Crowell, Jr., who was only a year away from graduation from Stanford University, was forever changed (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

The younger Crowell was forced to withdraw from Stan-ford because of deteriorating family finances. After a short stint at the less expensive University of California at Los Angeles, he got a job in the booming southern California steel industry at U.S. Steel's plant in Torrance. Several years later, a comment by a fellow worker whom he respected caused him to alter the course of his life. The fellow worker told him he was "a plain damn fool" for working for others if he had a fluorspar mine. Crowell did some checking into the market for fluorspar in southern California, and after receiving assurances that U.S. Steel, and later Bethlehem Steel, would purchase his fluorspar, he returned to Beatty in 1927 to work the mine (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

Upon his return to Beatty in 1927, Crowell, Jr., and Louis Vidano, who had faithfully remained in touch with the family, worked the fluorspar mine. The two men drilled and blasted by day and hoisted a few buckets of ore to the surface before going home at day's end. Crowell would return to town, eat, and then go back to the mine and work a second shift, climbing down the 134-foot shaft, loading a bucket with the purple ore, then climbing to the surface to hoist the ore and dump it. Then he would repeat the tedious, slow process. This he did until about 10 o'clock every night, seven days a week (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

In 1928, Crowell married his Los Angeles sweetheart, Dorothy. Prior to the marriage, Dorothy made a trip to Beatty with Crowell's mother to see if she liked the town and would want to live there. She found it agreeable, and the newlyweds set up housekeeping in the home the family still owns. The small-town desert community was a big change for Dorothy Crowell. There were no conveniences. Their house had only one spigot of running water, no electricity, and "there was no indoor 'biffy," she remembered. Baths were taken in a wash-bowl in the kitchen; water was heated on the stove in the winter and in a sun-warmed tank in the summer. The one convenience available in Beatty in 1928 was the telegraph, a necessity for the T&T Railroad (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987). The nearest emergency health care was in Las Vegas, then a small community and a full day's drive away over very poor dirt roads. All nonemergency medical care was obtained in Los Angeles (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

Both J. Irving, Jr., and Dorothy had relatives in southern California, so they made regular trips to that area. Trips to Los Angeles were true expeditions compared to the 5-hour journey in the 1990s. A trip from Beatty to Los Angeles by car took the Crowells three days. There were two possible routes: The first was north up Oasis Valley and across Sarcobatus Flat to the cutoff at Lida, over Westgard Pass and the White Mountains, and down into the Owens Valley. This leg of the journey, over dirt roads, took one day. They typically spent the first night in Big Pine, California. The next day they again drove over dirt roads as far as Mojave. At the end of the third day they would arrive in Los Angeles. The alternate route took them from Beatty to Las Vegas and on to Searchlight. From Searchlight they would travel to Goffs (following the Santa Fe tracks) and then west to Ludlow and Barstow, with dirt roads all the way to the summit of Cajon Pass. The tire problems encountered on these trips are nightmares by modern standards. In those days travelers did not carry spares; they carried casings, tubes, and patching. A flat tire meant removing the tire and patching the tube, replacing the tube and casing using clincher rims, and then pumping the tire up by hand. On one trip to Los Angeles, the Crowells had 28 flats, though several per day was a more usual figure. Trips to Las Vegas became more frequent after the closure of the T&T Railroad in 1940, because necessities were no longer shipped by rail (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).

Except for sporadic shutdowns during some of the worst years of the Depression in the 1930s, the Crowell fluorspar mine operated almost continuously between 1927 and 1989, producing in excess of 200,000 tons. It was a steady source of employment for a handful of miners, and at times employment peaked at 15 to 20 men. The ore pinches in and out, and the workings have varied over the years from only 6 inches to 70 or 80 feet in width. The small dump (where waste rock is disposed of) belies the mine's longevity because the Crowells have almost always dug on shipping-grade rock (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987; J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

In 1939, J. Irving Jr., acquired the first compressor for his fluorspar mine from the old Gold Ace Mine located near Carrara. It had two big flywheels and one cylinder, about 14 inches in diameter, and a glow plug that was heated with a blowtorch to get it started. It ran on a lowgrade diesel fuel. In the early 1950s, Crowell installed a six-cylinder International Harvester to run his compressor (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987; J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

For 30 years, Crowell used the same old Fairbanks-Morse single-cylinder gasoline engine for a hoist. In about 1951 he installed a 25-horsepower, three-phase electric hoist. The electricity was generated by a 125-horsepower International diesel with a 50-kw generator. The generator also supplied electric lights to the mine (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987, 1989).

The abandonment of three railroads in the Beatty area meant that for years miners did not lack mine timbers in the treeless desert. Railroad ties were so abundant and so easily accessible that they filled the need. Because railroad ties are 8 feet long by 8 inches wide, many tunnels in the older part of the Crowell Mine are 8 feet high and 8 feet wide, roomy by the standard of small mine operations. Some of the old ties used in the Crowell Mine still have railroad spikes sticking in them. The Crowell Mine still has the original headframe that was put in the 1920s, although it has occasionally been strengthened (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

The price of fluorspar has varied from about $11 a ton in 1917 to $23 a ton in the 1920, to $11 again in the Depression, and to the $60 range during the 1980s. Shipments averaged 500 to 600 tons of ore per month for many years. The fluorspar market has changed. At first fluorspar was sold to steel producers in southern California; more recently, with reductions in the amount of steel produced in the United States, the market has shifted to cement companies. In recent years, the ore was trucked from the Crowell Mine; in the early days, it was shipped on the railroad. After the closure of the T&T, the Crowells trucked the ore to Las Vegas, where it was put on the railroad. In recent years buyers provided their own transportation (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987; J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987). The mine closed in 1989. If market conditions change, it might reopen.

The Crowells raised two sons in Beatty: Jack was born in 1931 and Don in 1934. Both children attended the Beatty schools in the lower grades and went to high school in Las Vegas. After graduating from the University of Nevada in 1953 with a degree in mining engineering, Jack worked briefly in Telluride, Colorado, and joined the Navy in 1954. He returned to Beatty in 1957 and joined his father in operating the fluorspar mine (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

Jack Crowell was twelve years old when he started working three or four hours per day in his father's mine, helping the miners. The Crowell Mine then employed 12 people. Working with the rough-edged miners provided quite an education for the lad. Although given to some lurid descriptions and rough language, they were honest, hard-working people. Many were drifters and were on what miners still call "the circuit," a route that many miners travel, moving from one job to another. An idealized version of the route takes them from Arizona up to Idaho with the seasons-Arizona in the winter and Idaho in the summer. They never stay long on a job, perhaps only three to six months, and then they move on. But not all miners at the fluorspar mine were drifters on the circuit. Some were employed steadily by Crowell for ten or twelve years: Caesar Strozzi and his sons Joe and Harry, Ted "Bombo" Cottonwood, Gene Cross, and Harry Griffith (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

Jack Crowell noted, with a bit of nostalgia, that mining has changed in recent years. A generation ago, mining was a profession, even an art. In the old days, he said, a miner had to know a little bit of everything: how to run and operate drilling equipment, how to blast, how to muck the ore and tram it and hoist it, how to hand-sort the waste rock from the valuable ore; he had to be a plumber, and he had to lay track. He needed the skills of a carpenter and a millwright for he had to timber a shaft, a drift, or a stope, and he had to build ore chutes. Today a miner is a specialist; he usually operates a specific type of equipment: The modern miner can run a dragline, a rubber-tired loader, or a 100-ton dump truck (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

Early Milling Activity

Because of its railroads and the availability of water, Beatty was considered a convenient site for constructing mills to process ores mined in the region. In 1907 John W. Brock, the wealthy Philadelphian who owned the Tonopah Mining Company, purchased a major interest in the Tecopa Consolidated Mining Company and talked of building a $1.5 million smelter at Beatty. His plan was to use the lead ore from the Tecopa mine as a flux to treat the lower-grade, silicious ores from Tonopah and Goldfield. Tight money forced him to abandon his smelter idea and sell his shares in the company (Lingenfelter, 1986:357).After the failure of the Bullfrog district, there were rumors that there was still highgrade to be found in the mines. Of particular interest was the Original bullfrog Mine, with its famous high-grade, which legend said had once been displayed in the windows of Tiffany's. There were reports that the mine had produced $2 million (a wild exaggeration) and that a rich vein had faulted and been lost. In 1924, two leasers sank a shallow shaft at the mine and hit high-grade that ran $2600 a ton. They assumed they had found the lost "faulted vein," but shipped only a few thousand dollars' worth of ore. A number of people continued to work this property over the years, and one group even built a small mill at Beatty to process what they dug out (Lingenfelter, 1986:412).

Prior to the closure of the railroads, Beatty served as a railhead for many small mines in the area after the boom period was over. For example, leasers working lead claims after 1916 in the Ubehebe district on the northern slopes of the Panamint Range struck pockets of highgrade ore running about $100 a ton, and in 1921 and 1928, they shipped 1500 tons to the railhead at Beatty at a good profit (Lingenfelter, 1986:418-419).

In 1925, Charles Courtney Julian-a farmboy from the plains of Manitoba who became a flamboyant promoter involved in a multi-million-dollar oil swindle in California-formed the Western Lead Mines Company; he claimed he had found a fabulous deposit of lead at the head of Titus Canyon in the Grapevine Mountains. Buildings were constructed at the site, two tunnels were started, and a town called Leadfield was laid out. A road over the Grapevines to Beatty was constructed at a cost of between $40,000 and $60,000. Telephone and telegraph lines were run from Beatty (Lingenfelter, 1986:428-430). The company employed one hundred men. In January 1926, shares of Western Lead began selling on the Los Angeles Stock Exchange. The promotion reached a climax in March, when the "Julian Special" left Los Angeles with eleven Pullman sleepers, two diners, an observation car, and 340 enthusiasts on board. Eight hundred people drove down from Tonopah and Goldfield for the affair. On Sunday morning the enthusiasts made the 22-mile trek from Beatty to Leadfield over Julian's road. Stock jumped to a high of $3.30 on a 10-cent par. But the bubble soon burst; Julian's mine was exposed as a fraud, with his ore running less than $10 a ton and with only 200 tons in sight (Lingenfelter, 1986:430-431). Proving that a sucker is born every minute, Julian later returned to the people he had swindled on the Leadfield deal and bilked them again on a bogus silver mine in Arizona (Lingenfelter, 1986:433).

Conclusion

The town of Beatty was created by the excitement of the Bullfrog-Rhyolite boom, which was based on the hope that the gold deposits in the bullfrog Hills were both rich and deep. They were neither. Rhyolite and all the other small communities it spawned faded almost as quickly as they began. Beatty, however, had something going for it-location. In their history of Rhyolite, Harold and Lucile Weight wrote, "Beatty . . . was on the natural, shortest, bestwatered route between Goldfield and Las Vegas. Any main road, any railroad, was certain to go that way-as the highway goes today" (Weight, 1972:14). Beatty's accessibility and water supply made it possible for the small community to get through the first few years that are so critical in determining whether a Western boomtown will survive.Once a nucleus at Beatty had proven that it could survive after 1910, it became the economic and social center for a very large geographical area.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode https://ia800501.us.archive.org/11/items/AHistoryOfBeatty/beatty2.pdf

BEATTY, NEVADA

by Robert D. McCracken

Nye County Press

Tonopah NEVADA

The Land and Early Inhabitants

Exploration and Settlement

The Boom Is On

Beatty Beginnings

The Late 1920s to World War II

Rhyolite

A Joshua tree (yucca brevifolia)

Ash Meadows

Skidoo - Death Valley

Montgomery Hotel, Beatty 1905

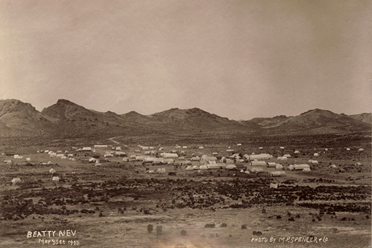

Beatty, Nv. 1905

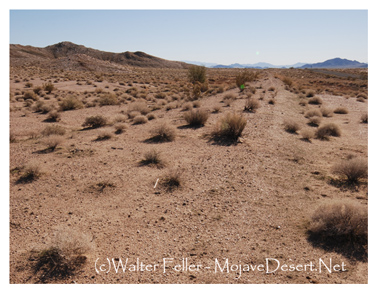

Tidewater & Tonopah RR

Tonopah, Nevada (UNLV photo)

T&TRR bed - Silver Lake Jan. 2011

Colemanite (USGS photo)

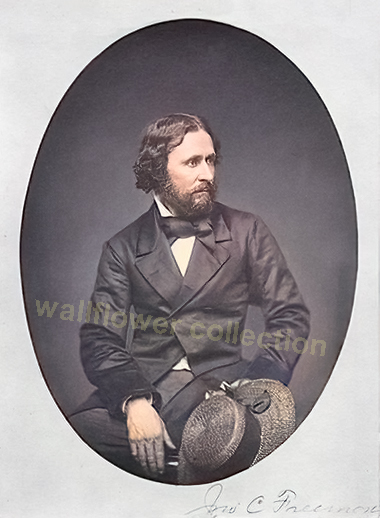

John C. Fremont

Amargosa River south of Death Valley Junction

Scotty's Castle

Emigrant Pass looking east

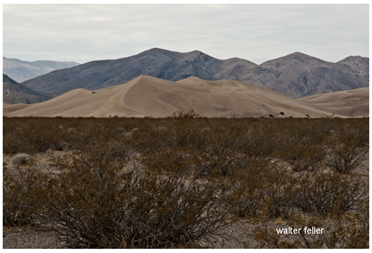

Big Dune

Cajon Pass

Chloride City

Death Valley Scotty

Goffs, Ca.

Harmony Borax Works

Leadfield - Death Valley National Park

Tonopah, Nv.

Tonopah, Nv.

Skidoo - Death Valley National Park

Waterman, Ca.

Goldfield Stage

Beatty Museum

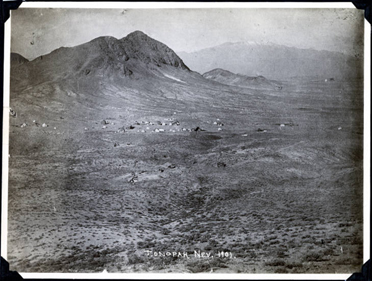

Bulllfrog/Rhyolite

Las Vegas, Nv. 1907

Railroad construction 1907 (UNLV)

Railroad construction 1907 (UNLV) S.P.L.A. & Salt Lake R.R. (UNLV)

S.P.L.A. & Salt Lake R.R. (UNLV)1 Prologue: The Land and Early Inhabitants

Location, Terrain, and Surrounding Features

How Beatty Got Its Name

Early Residents of the Beatty Area

2 Exploration and Settlement

Ogden's 1829-1830 Expedition

Fremont's Expeditions

Early Settlers: Lander and Stockton

Other Settlers in the Beatty Area

The Beatty Area at the Turn of the Century

3 The Boom Is On

The Montgomery Brothers: The Boom Begins

Shorty Harris and Ed Cross: "Lousy with Gold"

Montgomery "Re-infected" with Gold Fever

Shorty Loses His Claim

The Rhyolite Boom

Pioneer and Skidoo: The Last Hurrah

When Gold Was Not Enough

4 Beatty Beginnings

Bob Montgomery Founds Beatty

Newspapers in the Bullfrog District

Hauling Freight: Before the Railroads

The Railroads Reach Beatty

The Last Years of Old Man Beatty

Judge William Gray: Long-time Resident

J. Irving Crowell and the Chloride Cliff Mine

The Crowells' Fluorspar Mine

Early Milling Activity

Conclusion

5 The Late 1920s to World War II

Mining Slacks Off

The Reverts Boost the Beatty Economy

Other Economic Activity

Lisle Contributes to Beatty's Transportation Economy

The Bootleg Business

Scotty's Castle: "Neither of Us Pays Rent"

People of Beatty

Electric Power and Waste Disposal

Phone Service

Pioneer Educators

Children at Play

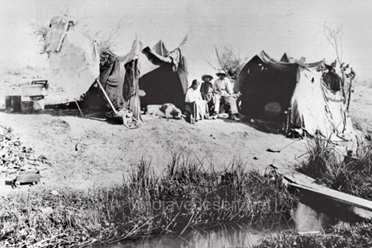

The Beatty Indians in the 1920s and 1930s

Conclusion