The Boom Is On

There is a principle that governs all activity in the mining business. It might be called The First Law of Prospecting: You only find gold (or anything else for that matter) if you look for it. If you don't look, you don't find! The great twentieth-century boom camps at Tonopah, Goldfield, and Round Mountain were based on the discovery of precious metal deposits that literally stuck out of the ground. Native Americans had walked over the veins for millennia. Yet the blackstained stone at Tonopah and the gleaming flecks of gold in the rocks at Goldfield and Round Mountain had no meaning to the Indians; they weren't looking. The same can be said for the many travelers, ranchers, and outlaws who trekked over those outcroppings unaware of what fabulous treasures lay at their feet.The gold in the green rock at Bullfrog had been there for millions of years; but it took the keen eye of an individual who could recognize what he saw to make the discovery. God put the gold at Bullfrog, but it wasn't for anybody to find. It took someone who knew about different types of rocks and the geologic formations and the indications of where gold might occur. It took someone who could survive on the desert with a burro, a blanket, a gold pan, and 30 miles by foot between water holes. It took someone who knew loneliness, a man of the desert, a true pioneer, a starry-eyed dreamer, a chaser of rainbows, perhaps even a fool, a ne'er-do-well by some city standards-a prospector.

The Montgomery Brothers: The Boom Begins

The Montgomery brothers, George, Frank, and Ernest Alexander (also known as Bob), started the great gold boom in the Death Valley area. They found the gold that opened the rush, they were behind the opening of the first big mines, and they stayed for more than twenty years until the boom was over. The Montgomery brothers were born in Canada and moved with their parents to a farm in Stuart, Iowa, after the Civil War. In 1884 they went west and worked in the mines in Wood River, Idaho (Lingenfelter, 1986:189). In late 1890, George was the first of the brothers to come to Death Valley; while looking for the Lost Breyfogle, he discovered the Chispa Mine (chispa is Spanish for "a nugget") about 50 miles southeast of the bullfrog Hills in the Last Chance Range, which separates the Amargosa and Pahrump valleys. The discovery was one of several in the area. A few months later, about four miles to the north, the deposit at Johnnie was found by John Tecopa, the son of Chief Tecopa; and the Younts discovered the North Belle Mine a short distance away about the same time (Lingenfelter, 1986:18, 189-190).In 1896 the Montgomery brothers discovered gold in the Panamint Mountains and named their claim the World Beater Mine. Eventually, the town of Ballarat was established nearby (Lingenfelter, 1986:194). In 1897 Bob Montgomery and a couple of partners made yet another discovery in a nearby canyon and they named it for their favorite whiskey: Oh Be Joyful (Lingenfelter, 1986:198). By 1900 ballarat was the leading camp in the Panamints, with nearly 300 men working in the area mines (Lingenfelter, 1986:195, 199). But the discoveries at Tonopah in 1900 led to a mass exodus from the Panamints and ballarat in 1901, and most of what was left of the town was destroyed by a flash flood that summer (Lingenfelter, 1986:200).

In 1903 George Montgomery returned to ballarat to restake his claim on the abandoned World Beater, which produced significant quantities of bullion before the high grade was exhausted in 1905. In 1905 discoveries at Bullfrog once again led to abandonment of ballarat (Lingenfelter, 1986:202). Bob Montgomery left ballarat and settled in Tonopah in 1901. He married and began to work as a jeweler and an optician; but his passion for gold was only temporarily cooled.

Shorty Harris and Ed Cross: "Lousy with Gold"

Frank "Shorty" Harris and Ernest "Ed" Cross are credited with the discovery on August 4, 1904, of "the fabulous gold-speckled green rock" found in the bullfrog Hills a few miles southeast of what was to become the town of Rhyolite (Weight, 1972:3). Born in Rhode Island on July 21, 1857, Harris was orphaned at the age of seven. In the late 1870s he rode the rails west to seek his fortune in the mines. He searched in Leadville, Tombstone, the Coeur d'Alenes, and Death Valley. Harris, called Short Man by the local Indians (Caruthers, 1951:122), had a big, bushy mustache, blue eyes, big ears, and was barely 5'4" tall. He was known for his weakness for whiskey-the Oh Be Joyful. Cross has been described as a quiet, sober young newlywed (Lingenfelter, 1986:203). Shorty and Ed always disagreed about who really made the Bullfrog discovery. According to Shorty,I didn't get in early enough at Tonopah and Goldfield, so I wandered south and followed the Keane Wonder excitement in the Funeral range. I got there about as late as I did elsewhere, so I didn't get any close-in ground. Long before the Keane Wonder was struck, I had traveled across the country from Grapevine to Buck Springs, and had seen the big blowout of quartz and quartzite on the ground that later I located as the Bullfrog claim. When I found that I couldn't get anything good at the Keane Wonder, I remembered the blowout and decided to go back to it. E. L. Cross was at the Keane Wonder; he was there afoot.

"Shorty, I'd like to go with you," said Cross.

"Your chance is good," said I, "Come along!" (Ritter, 1939 [19821:1-2).

In a 1930 interview for Westways, Shorty Harris described what next happened: So we left the Keane Wonder, went through Boundary Canyon, and made camp at Buck Springs, five miles from a ranch on the Amargosa where a squaw man by the name of Monte Beatty lived. The next morning while Ed was cooking, I went after the burros. They were feeding on the side of a mountain near our camp, and about half a mile from the spring. I carried my pick, as all prospectors do, even when they are looking for their jacks-a man never knows just when he is going to locate pay-ore. When I reached the burros, they were right on the spot where the Bullfrog mine was afterwards located. Two hundred feet away was a ledge of rock with some copper stains on it. I walked over and broke off a piece with my pick-and gosh, I couldn't believe my own eyes. The chunks of gold were so big that I could see them at arm's length-regular jewelry stone! In fact, a lot of that ore was sent to jewelers in this country and England, and they set it in rings, it was that pretty! Right then, it seemed to me that the whole mountain was gold.

I let out a yell, and Ed knew something had happened; so he came running up as fast as he could. When he got close enough to hear, I yelled again:

"Ed, we've got the world by the tail, or else we're coppered!"

We broke off several more pieces, and they were like the first-just lousy with gold. The rock was green, almost like turquoise, spotted with big chunks of yellow metal, and looked a lot like the back of a frog. This gave us an idea for naming our claim, so we called it the Bullfrog. The formation had a good dip, too. It looked like a real fissure vein; the kind that goes deep and has lots of real stuff in it. We hunted over that mountain for more outcroppings, but there were no others like the one the burros led me to. We had tumbled into the cream pitcher on the first one-so why waste time looking for skimmed milk?

That night we built a hot fire with greasewood, and melted the gold out of the specimens. We wanted to see how much was copper, and how much was the real stuff. And when the pan got red hot, and that gold ran out and formed a button, we knew that our strike was a big one, and that we were rich (Harris, 1930:18).

According to Shorty, the two waited until the next day to locate claims. Then they went over and showed the rich rock to Old Man Beatty, who immediately rushed over and located his own claim. George Davis heard about the strike and staked some ground for himself to the east. Harris and Cross told M. M. Detch, Len McGarry, and Bob Montgomery-the word quickly spread and the great Rhyolite boom was on (Ritter, 1939 [1982]:2). In his version, Cross contended he was out digging and sampling one morning when he picked up a specimen about the size of a hen's egg that was heavy with gold. He said he took it back to camp, tested it, and then called Shorty (Weight, 1972:4). Most authorities credit Shorty with the discovery, however, if for no other reason than he seems to better fit the image of such a discoverer (Weight, 1972:3).

Montgomery "Re-infected" with Gold Fever

Montgomery, who was living in Tonopah at the time of Shorty and Ed's discovery, ran into Ed in Goldfield and was once again "mineralized"-a term the prospectors used to describe those infected by the gold bug. Shorty Harris described the scene:After the monuments were placed, we got some more rich samples, and went to the county seat to record our claim. Then we marched into Goldfield, and went to an eating-house. Ed finished his meal before I did, and went out into the street where he met Bob Montgomery, a miner that both of us knew. Ed showed him a sample of our ore, and Bob couldn't believe his eyes.

"Where did you get that?" he asked.

"Shorty and I found a ledge of it southwest of Bill [sic] Beatty's ranch," Ed told him.

Bob thought he was having some fun with him and said so.

"Oh, that's just a piece of float that you picked up somewhere. It's damn seldom ledges like that are found!"

Just then I came walking up, and Ed said, "Ask Shorty if I ain't telling you the truth." "Bob," I said, "that's the biggest strike made since Goldfield was found. If you've got any sense at all, you'll go down there as fast as you can, and get in on the ground floor!" That seemed to be proof enough for him, and he went away in a hurry to get his outfit together-one horse and a cart to haul his tools and grub (Harris, 1930:19). In September 1904, Montgomery headed for Bullfrog on a $75 grubstake by three Goldfield investors. He was unsuccessful and stayed only a few days.

On the way back to Goldfield, he stopped at John Howell's ranch in Oasis Valley (Lingenfelter, 1986:168, 207). There he met a young Shoshone known as Hungry Johnny, who claimed to know where ore could be found. Montgomery hired him to stake out two claims. Three weeks later, they met at Old Man Beatty's ranch and Hungry Johnny showed Montgomery the claims (Lingenfelter, 1986:207).

The claims, seemingly only a crumbly deposit of pink talc, did not look promising; but Montgomery took a chance and staked out two more adjoining claims-the Shoshone Nos. 2 and 3. The first assays ran less than $5 per ton. Montgomery took more samples and was still having no luck when, for an interest in the claims, a wizened old prospector named Al James agreed to show Montgomery where good gold values could be obtained on the Shoshone No. 3. Montgomery took samples in the talc where James designated and they ran $300 per ton in gold. An experienced miner, Montgomery wanted to get under the ore and cut it at depth and so a tunnel was driven below the deposit. He struck ore 70 feet thick that was assayed as high as $16,000 a ton (Lingenfelter, 1986:207). Tears filled Bob Montgomery's eyes when he first saw his new bonanza: "I have struck it; the thing that I have dreamed about since I was 15 years old has come true; I am fixed for life and nobody can take it away from me," he said (Lingenfelter, 1986:208). His find was heralded as "the greatest discovery ever made on the desert," "richer than the mines of King Solomon" (Lingenfelter, 1986:208). Montgomery's discovery and reports of fabulous assays from surrounding claims were ballyhooed nationwide (Lingenfelter, 1986:211).

Shorty Loses His Claim

After Harris and Cross made their discovery, they had assays run in Goldfield. The first showed $665 a ton in gold, and other samples reached $3000 (Lingenfelter, 1986:204). Once in Goldfield, Shorty characteristically headed for the saloons and the Oh Be Joyful. Cross quickly lined up a sale of their claims for $10,000, but the deal could not be completed because Shorty could not be found to close it. Shorty sobered up six days later, only to find that while he was in a drunken stupor he had sold his half of the claim for the low price of $1000, which he promptly spent on more drinks. Cross joined with J. W. McGalliard, who had purchased Shorty's portion of the claim, and together they formed a stock company, the Original bullfrog Mines Syndicate. Cross eventually sold his interest in the syndicate to a San Francisco broker for a reported $125,000, and he and his wife used the money to buy a big ranch near Escondido (Lingenfelter, 1986:204).Harris later gave this account of the disposal of his share of the Bullfrog claim. I woke up one morning and judging from the empties, I must have had a grand evening. I reached for a full pint on the table and under it was a piece of paper with a note. I read it and learned for the first time that I'd sold the Bullfrog (Caruthers, 1951:54).

Harris knew that the law would have released him from the contract, but as a man true to his word he declared, "I signed it." Years later he said, "At that, I got good money for a fellow like me," adding "I've never wanted for anything" (Caruthers, 1951:54-55).

If I'd got those millions the big boys would have hauled me off to town, put a white shirt on me. Maybe they would have made me believe Shorty Harris was important. "Mr. Harris this and Mr. Harris that." I've got something they can't take away. I step out of my cabin every morning and look it over-100 miles of outdoors. All mine (Caruthers, 1951:55).

The Rhyolite Boom

Shorty Harris and Ed Cross were in Goldfield for only a few days. But word of their discovery in the bullfrog Hills spread quickly. Goldfield and Tonopah were filled with "boomers," who had gotten to those towns too late to stake a valuable claim or in some other way to capitalize on the excitement. Most did not wait around for Shorty and Ed to head south to their claims; they gathered what information they could on the location and struck out on their own. Time was of the essence; a delay of a few hours, even a few minutes, could mean the difference between becoming rich and getting nothing. Shorty Harris described the scene he and Ed encountered when they arrived back at the site of their discovery:When Ed and I got back to our claim [Shorty speaks of the claim as his, but he had sold his interest.] a week later, more than a thousand men were camped around it, and they were coming in every day. A few had tents, but most of 'em were in open camps. One man had brought a wagonload of whiskey, pitched a tent, and made a bar by laying a plank across two barrels. He was serving the liquor in tincups, and doing a fine business.

That was the start of Rhyolite, and from then on things moved so fast that it made even us oldtimers dizzy. Men were swarming all over the mountains like ants, staking out claims, digging and blasting, and hurrying back to the county seat to record their holdings. There were extensions on all sides of our claim, and other claims covering the country in all directions. In a few days, wagonloads of lumber began to arrive, and the first buildings were put up. These were called rag-houses because they were half boards and half canvas. But this building material was so expensive that lots of men made dugouts, which didn't cost much more than plenty of sweat and blisters (Harris, 1930:19).

By September 1904, there were 75 men camped at Beatty's ranch alone. A returning Goldfielder met 52 outfits headed toward the new bonanza (Weight, 1972:7). "'What a procession!' the Rhyolite Herald recalled. 'Men on foot, burros, mule teams, freights, light rigs, saddle outfits, automobiles, houses on wheels-all coming down the line from Tonopah and Goldfield, raising a string of dust 100 miles long' (Weight, 1972:7). R. A. Gibson, who was traveling from Chicago to Los Angeles by train, heard about the strike. He got off at Needles, gave the remainder of his ticket to a bum, and hired on as a swamper in order to reach the new bonanza. An 18-mule outfit belonging to H. D. and L. D. Porter, loaded with selected merchandise from their store in Randsburg, California, headed across Death Valley for Rhyolite in March and April 1905.

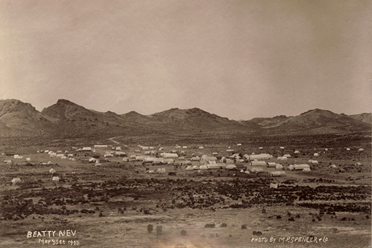

A covey of towns sprang up in the area adjoining the big strike. By mid-March 1905, Bullfrog had 20 tents and a population of 40; Amargosa, located 1 mile below bullfrog, had 80 tents and a population of 160; Rhyolite had 100 tents and a population of 200; Bonanza had 1 tent; Gold Center had 20 tents; and the town of Beatty, the most propitiously located of all the communities in terms of the availability of water, had 150 tents and a population of 300 (Weight, 1972:7). Rhyolite, which lay in a horseshoe valley at the base of the mountains below Montgomery's Shoshone Mine, became the center of activity for the district; and the Shoshone became the "boss mine" of the bullfrog district (Lingenfelter, 1986:209).

With characteristic hyperbole, Harris described Rhyolite's growth.

Rhyolite grew like a mushroom. Gold Center was started four miles away, and Beatty's ranch became a town within a few months. There were 12,000 people in the three places, and two railroads were built out to Rhyolite. Shipments of gold were made every day, and some of the ore was so rich that it was sent by express with armed guards. And then a lot of cash came into Rhyolite-more than went out from the mines. It was this sucker money that put the town on the map quick. The stock exchange was doing a big business, and I remember that the price of Montgomery-Shoshone got up to ten dollars a share (Harris, 1930:19-20).

Senator William M. Stewart, a Comstock veteran and a renowned Nevada politician and mining lawyer, became a resident of Bullfrog (Weight, 1972:10). Senator Stewart owned an entire block on Main Street in Bullfrog, and his office and residence were the finest in the district. His office included a 1200-volume law library, said to be the best in the state (with the possible exception of the State Library at Carson City) (Weight, 1972:12). Stewart is quoted as saying, "If I had twenty grandsons I would plant them all in Bullfrog and let them grow up to be millionaires during the course of this present decade. . . . I look forward to seeing the early days of Cripple Creek and Goldfield duplicated." From the district, he said, "would arise in time the greatest camp the West has ever seen" (Weight, 1972:10).

But Bullfrog faded rapidly and by the end of May 1905, its population of 300 was eclipsed by Rhyolite's 1500 (Weight, 1972:10). There were 20 saloons operating in Rhyolite then (Weight, 1972:8). Initially, water was unavailable in Rhyolite and had to be hauled from Beatty by burro in whiskey barrels. The water tasted like whiskey and sold for $5 a barrel. In the summer of 1905, three rival companies completed pipelines from Beatty, Indian Springs, and Terry Springs to Rhyolite. Telephone service reached Rhyolite early in 1905. Electric power was first generated locally, then brought in from hydroelectric plants on Bishop Creek in California (Lingenfelter, 1986:222).

One week after completing a 270-mile trip overland from Caliente to Rhyolite via Goldfield with a freighter who did not know the direct route, Editor Earle R. Clemens brought out the first issue of the Rhyolite Herald on Friday, May 5,1905 (Weight, 1972:7). A few weeks later, the Herald carried the following story.

Rhyolite spread canvas faster than any town on the Nevada desert. Men scrambled to buy or lease the most favorable locations, regardless of price. The grocer, the baker, the booze dispenser .. . the druggist, the clothier, the hardware dealer, the newspaper man, the gambler, the hasher, the lodging house keeper, almost with one accord, hung out their signs and shingles. Within a few days every line of business and profession was represented and a full fledged community had been established.

Concord Stages, drawn by fours and sixes, came daily from Goldfield, 75 miles on the north, and Las Vegas, 125 miles on the south. Automobiles by the score came from Tonopah and Goldfield. From Goldfield stage fare was $18, auto $25. From Las Vegas the stage was $25, the trip took two days, one night. From Las Vegas freight took six to eight days, and dry camps had to be made.

The rainbow-chasers were crowded into canvas lodging houses partitioned with cheesecloth or burlap-proof against neither sight nor sound (Weight, 1972:8-10). By 1907, the population of Rhyolite was 6000, making it the fourth largest town in Nevada, after Goldfield (estimated 20,000), Tonopah (estimated 10,000), and Reno (estimated 8,000) (Rocha, 1980:4). In 1907, 50 cars of freight were arriving daily on the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad. Lots in the heart of Rhyolite sold for $10,000 (Latschar, 1981:9). In January 1908, the John S. Cook & Co. Bank Building on Golden Street in Rhyolite was completed. The three-story building cost more than $90,000 and was constructed of concrete, steel, and glass, with Italian marble stairs, imported stained glass windows, and Honduran mahogany trim (Lingenfelter, 1986:219).

The boom, of course, was predicated upon the assumption that the hills around Rhyolite held valuable deposits of gold. The gold would be extracted by mining companies and there was the expectation of high profits, which would be reflected in stock prices. Such excitement led to the formation of more than 200 Bullfrog mining companies, which floated over 200 million shares of stock on the public. Most companies incorporated the name bullfrog: Giant bullfrog, bullfrog Merger, bullfrog Apex, bullfrog Annex, bullfrog Gold Dollar, bullfrog Daisy, bullfrog Starlight, bullfrog Puritan, bullfrog Outlaw, bullfrog Mogul. Bob Montgomery and his partners formed a stock company, the Montgomery Shoshone Mine Company, in April 1905. Montgomery, who held three-quarters of the stock, boasted that he could take out $10,000 a day from his mine; the first shipment of ore was rumored to average $2300 a ton. There was talk of a big stamp mill to be constructed in Beatty, with a 3-mile aerial tram to the mine, but Montgomery's partners were already seeking a buyer. John W. Brock, the Philadelphia financier who had bought Jim Butler's mine in Tonopah, was approached, but his advisers cautioned him against the purchase because they thought the deposit was superficial (Lingenfelter, 1986:211- 212).

In early 1906, Bob Montgomery sold his interest in the Montgomery Shoshone Mine to Charles Schwab, "the new saint of the American Dream of rags to riches, the epitome of upward mobility" (Lingenfelter, 1986:217). Schwab had risen from an engineer's helper at the age of eighteen to president and part owner of the Carnegie Steel Company at age thirty-five. Later, Schwab became president of U.S. Steel and was reportedly "the highest salaried man in the world," making over $2 million a year, with stock holdings in the tens of millions (Lingenfelter, 1986:216-217). Under Schwab's ownership nearly 2 miles of tunnels and drifts were developed at the Montgomery Shoshone Mine, and a mill that handled 300 tons per day was constructed at the mine, with water supplied by an 11-mile pipeline from Goss Spring. It was the biggest and most modern mill the Death Valley region had ever seen (Lingenfelter, 1986:218). Schwab arranged the mine's finances so that he would be paid back before any of the stockholders. Such an arrangement proved to be good foresight, for the mine's ore reserves proved to be neither deep nor extensive-the Montgomery Shoshone Mine was closed March 14, 1911. "The Montgomery Shoshone is dead," the Rhyolite Herald cried on March 25, 1911. Although the mine had produced $1,418,636.21 in bullion, it never paid a dividend. Its "profit" ($432,000) was partial repayment for Schwab's loans. When the mine closed, the mill and other machinery were sold to pay off the remaining $100,000 he was owed. Shareholder profits, it seemed, had gone "a glimmering" (Lingenfelter, 1986:239). It has been suggested that crushed ore at the Montgomery Shoshone mill suffered from "sliming"-forming such a fine material that metallurgical problems resulted in inadequate recovery of gold values in the ore (Hall, 1989:5).

Although Rhyolite experienced growth from 1904 to about 1907, the boom faded almost as quickly as it had appeared. The ore deposits, apparently lacking size and depth, simply could not long support a boomtown. Deposits might present good indications, but they quickly became exhausted. The Montgomery Shoshone mill continued to process low-grade ore, but there was nothing romantic about low-grade ore (Latschar, 1981:17). By disrupting financial markets, the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 slowed development (Latschar, 1981:9). The financial panic of 1907 affected other areas in Nevada and California more than it did Rhyolite (Latschar, 1981:12). In reality, the Rhyolite boom was predicated on speculation and could not be sustained. When news of shady dealings involving two of the district's most promising mines surfaced, investor confidence was eroded; and the March 1911 closure of the Montgomery Shoshone, the only mine in the district even to show significant production, was the final blow (Latschar, 1981:17).

One month later, on April 8, 1911, Rhyolite Herald Editor Clemens wrote (Weight, 1972:32): "It is with deep regret that I announce my retirement from the newspaper field in the bullfrog district. It has been my lot to remain here while all my erstwhile contemporaries have fled, one by one, to more inviting localities, and now it is my time to say goodbye." Clemens went on to describe Rhyolite as "the prettiest, coziest mining town on the great American desert, a town blessed with ambitious, hopeful, courageous people, and with a climate second to none on earth. Goodbye, dear old Rhyolite." George Probasco, who kept the newspaper going for another month, wrote: "Rhyolite was about the biggest mining boom and bust that ever happened. Until 1908, the sagebrush was full of millionaires who a year or so later were wondering about their next meal ticket or a free ride out of town" (Weight, 1972:32). Service to Rhyolite by the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad was discontinued in 1914, and in 1916 the Nevada Power Company cut off electricity (Latschar, 1981:19).

Most businesses had shut down or moved by 1911, and the 1920 census found only 14 residents. A 1922 motor tour of Rhyolite by the Los Angeles Times found Rhyolite's only resident to be a 92-year-old man, who by 1924 had died (Hall, 1989:6).

Rhyolite's remains served mainly as a source of buildings and building supplies to be scavenged for use in other towns and camps. Many buildings were moved to Beatty: The Miners' Union Hall became the Old Town Hall; one- and two-room cabins were assembled into multi-room homes (Lisle, 1987); and pieces of numerous buildings were used to construct a school in Beatty. It is said some of the buildings eventually ended up in Boulder City, Nevada, to house workers when Hoover Dam was constructed in the early 1930s (Bradhurst, 1991). The desolate scene at Rhyolite was described by William Caruthers. Caruthers, a journalist who came to the Death Valley area in 1926 and spent the next twenty-five years observing life there, made a fire and camped in the empty streets of Rhyolite on January 1, 1926.

The next morning I poked around in the abandoned stores to marvel at the things of value left behind. Chinaware and silver in hurriedly abandoned houses and in the leading cafe. The cribs [one-room cabins used by prostitutes] still bore the castoff ribbons and silks of the girls and for all I know, the satin slipper which I found on a bed may have been the one that Shorty Harris filled with champagne to toast the charms of Flaming Jane" (Caruthers, 1951:55).

As the town's few remaining buildings decayed and ghosts of faded dreams took up residence among the ruins, Holly-wood used the picturesque site as a film location. For a 1925 movie, Paramount Pictures restored the famous Bottle House, built of an estimated 50,000 bottles during the town's peak (Hall, 1989:6). Orion Pictures used Rhyolite's ruins as the setting for its 1987 science-fiction movie "Cherry 2000," which depicted American society in collapse. Production figures for the great Tonopah, Goldfield, and Rhyolite-bullfrog booms between the time of their discovery and 1920 are revealing (Elliott, 1966:311). Tonopah is credited with production of more than $109 million; Goldfield, $80 million; and Rhyolitebullfrog lags far behind with only about $1.8 million. Clearly, Rhyolite was based more on a dream of economic wealth than on reality-that harsh arbitrator of the fate of boomtowns.

Pioneer and Skidoo: The Last Hurrah

The presence of Pioneer, a short distance north of Rhyolite (2 miles west of the Springdale Station on the bullfrog Gold-field Railroad), had arrested the decline of Rhyolite for a short time beginning in late 1908 (Latschar, 1981:17). The Bi-Metallic Mine, the chief producer at Pioneer, was the only mine in the area that came close to equaling the Montgomery Shoshone. The Bi-Metallic was purchased by Denver promoters in 1905. Later, a new company was formed, and in 1908 considerable rich ore was struck. Shipments from the Bi-Metallic Mine reached $60,000 a month in 1909, but before the end of July the mine became entangled in litigation and most of the town's residents left by the end of the summer. In early 1909, Pioneer's population reached about 2500, briefly surpassing the population of Rhyolite. The Western Federation of Miners, which had formed a local at Rhyolite, formed a new local at Pioneer. The community also had its own newspaper. Fire gutted the main business block of Pioneer on May 7, 1909, but the bank and red-light district were mercifully spared. The block was rebuilt by July 4, but by the end of the month the boom collapsed due to the tangle of litigation (Lingenfelter, 1986:230-233).The last of the Death Valley gold boomtowns-Skidoo was born in 1906. Bob Montgomery, who had become an instant millionaire when he sold his share of the Montgomery Shoshone Mine to Charles Schwab, continued to invest in mining. He purchased and developed 23 claims in the Panamints (Lingenfelter, 1986:286). His wife, Winnie (who purchased an alligator and pheasant farm in Mexico), named the area of the new claims Skidoo, after the popular phrase "23 Skidoo" (Lingenfelter, 1986:216, 287). After the closure of the Keane Wonder Mine in the summer of 1916, "Bob Montgomery's Skidoo became the last survivor of the Death Valley gold boom" (Lingenfelter, 1986:307).

The rush to Skidoo began in May 1906. In July Montgomery laid out a town just north of the mine. He called the town Montgomery, but everybody else called it Skidoo and it was officially so designated on April Fool's Day, 1907 (Lingenfelter, 1986:289). The 56-mile road over Daylight Pass from Bull-frog to Skidoo was constructed in 1906 (Lingenfelter, 1986:290). The Skidoo Mine produced until September 1917 and yielded a total of $1,344,500 in gold, which made it the second largest producer in the Death Valley-Amargosa region. Its yield was just 5 percent short of the Montgomery Shoshone production total (Lingenfelter, 1986:308).

When Montgomery's final profit sheets were totaled, he ended up with a profit of less than 1 percent per annum over the period of the operation of the mine (Lingenfelter, 1986:308). By 1917 he had lost most of his money; none of his other mining ventures had panned out, and he also lost money in oil speculations in Mexico. He continued to speculate in mining for the remainder of his life and was working on a "deal" when he died on August 15,1955, in Clovis, New Mexico, at the age of ninety-one. As Lingenfelter observed, the Death Valley gold boom lasted a quarter of a century; George Montgomery had been a part of its beginning at the Chispa Mine in 1890 and Bob Montgomery was there when it ended in 1917 (Lingenfelter, 1986:308-309).

A story in the Bullfrog Miner ("Sensation of the Mining World," May 12,1906) captures the optimism-however fleeting-associated with most Nevada boomtowns.

Just a few years ago it was Tonopah, Goldfield, and Bullfrog, in succession; a few months ago, it was Manhattan, Golddyke, Palmetto; a few weeks ago, comparatively, it was Fairview, Golden Arrow, Cueprite.

A few days ago it was Buckskin that started a sensation. All the mining camps mentioned are in Nevada, but not all the mining camps in Nevada are mentioned. The mining camps of New Nevada are springing up like magic, and the best part of the story is that a remarkably large proportion of these camps is "making good." At least five of these mentioned have come to stay, and expert judgment is that either one of these five will make it better than a Butte, or a Park City, or a Cripple Creek. . . . Nevada, for the next few years, promises to be the sensation of the mining world.

When Gold Was Not Enough

Although prospectors were often single minded in the pursuit of gold and wealth, they sometimes felt the need for companionship and love. But women were almost always in short supply in the Western frontier mining towns. The Beatty-Death Valley area was no exception- many of the prospectors and boomers were consigned to living alone. But that did not stop the Chaplinesque Shorty Harris from falling in love, though his objet d'amour was at least 8 inches taller than he was and probably outweighed him by more than 70 pounds. Harris tells of his illfated last attempt to marry.I knew a girl in ballarat by the name of Bessie Hart. She was a mighty fine woman and a good cook. No one in camp dared to pull any rough stuff around her-she was six feet tall, weighed 210 pounds, and could lick a husky man. I don't know why a little hammered-down fellow like me should fall in love with a woman like that-but I did just the same.

One day I was up by the Stone Corral sharpening picks in the blacksmith shop, and Bessie was blowing the bellows for me. Two of her best friends, Dean Harrison and Tom Walker, had gone to Tonopah, and she was missing them a lot, and I thought this would be a good chance for me. "Miss Bessie," I said, "I guess you're kind of lonesome now since Dean and Tom are gone?"

"Oh, a little," she said.

"Well now, we've been kind of friendly for several years, and since they aren't likely to come back, what's the matter with me and you getting married?"

She didn't say anything for a minute or two-just looked me over from head to foot- just gave me the top and bottom stuff, and I wondered if she was going to speak.

"Shorty," she said finally. "I like you. .. . You're a good friend and a handy little fellow to play with. But you're too little for hard work!"

That was all I needed to show me that I was out of luck when it came to getting a wife, and I've never tried since. .. . But even if I've never been lucky at the game of love, I've had some good breaks when I was looking for gold (Harris, 1930:18).

Shorty was right. He never married, although he went on to make other discoveries of gold in the Death Valley area. However, he never became a wealthy man. Shorty Harris died November 10,1934, and is buried in Death Valley. His epitaph is said to read: "Here lies Shorty Harris, a single blanket jackass prospector" (Weight, 1972:6).

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode https://ia800501.us.archive.org/11/items/AHistoryOfBeatty/beatty2.pdf

BEATTY, NEVADA

by Robert D. McCracken

Nye County Press

Tonopah NEVADA

The Land and Early Inhabitants

Exploration and Settlement

The Boom Is On

Beatty Beginnings

The Late 1920s to World War II

Rhyolite

A Joshua tree (yucca brevifolia)

Ash Meadows

Skidoo - Death Valley

Montgomery Hotel, Beatty 1905

Beatty, Nv. 1905

Tidewater & Tonopah RR

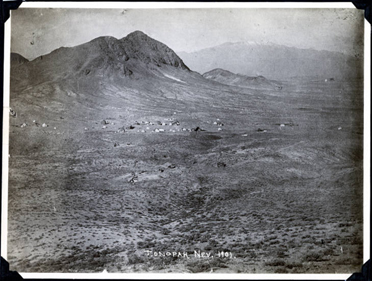

Tonopah, Nevada (UNLV photo)

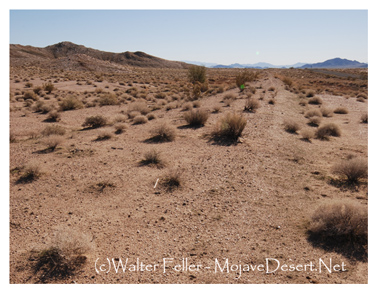

T&TRR bed - Silver Lake Jan. 2011

Colemanite (USGS photo)

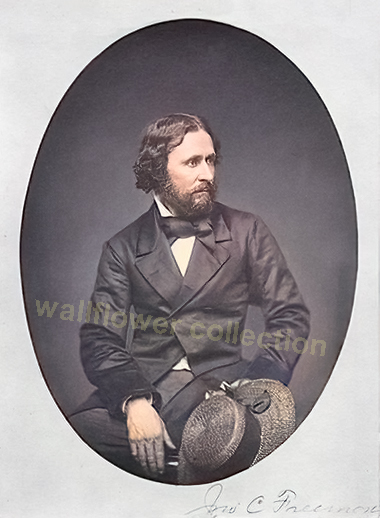

John C. Fremont

Amargosa River south of Death Valley Junction

Scotty's Castle

Emigrant Pass looking east

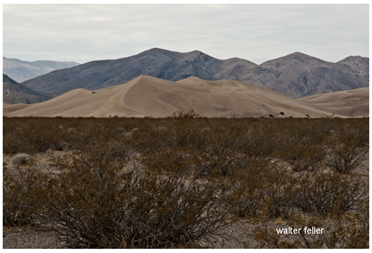

Big Dune

Cajon Pass

Chloride City

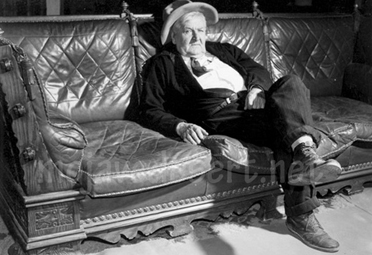

Death Valley Scotty

Goffs, Ca.

Harmony Borax Works

Leadfield - Death Valley National Park

Tonopah, Nv.

Tonopah, Nv.

Skidoo - Death Valley National Park

Waterman, Ca.

Goldfield Stage

Beatty Museum

Bulllfrog/Rhyolite

Las Vegas, Nv. 1907

Railroad construction 1907 (UNLV)

Railroad construction 1907 (UNLV) S.P.L.A. & Salt Lake R.R. (UNLV)

S.P.L.A. & Salt Lake R.R. (UNLV)1 Prologue: The Land and Early Inhabitants

Location, Terrain, and Surrounding Features

How Beatty Got Its Name

Early Residents of the Beatty Area

2 Exploration and Settlement

Ogden's 1829-1830 Expedition

Fremont's Expeditions

Early Settlers: Lander and Stockton

Other Settlers in the Beatty Area

The Beatty Area at the Turn of the Century

3 The Boom Is On

The Montgomery Brothers: The Boom Begins

Shorty Harris and Ed Cross: "Lousy with Gold"

Montgomery "Re-infected" with Gold Fever

Shorty Loses His Claim

The Rhyolite Boom

Pioneer and Skidoo: The Last Hurrah

When Gold Was Not Enough

4 Beatty Beginnings

Bob Montgomery Founds Beatty

Newspapers in the Bullfrog District

Hauling Freight: Before the Railroads

The Railroads Reach Beatty

The Last Years of Old Man Beatty

Judge William Gray: Long-time Resident

J. Irving Crowell and the Chloride Cliff Mine

The Crowells' Fluorspar Mine

Early Milling Activity

Conclusion

5 The Late 1920s to World War II

Mining Slacks Off

The Reverts Boost the Beatty Economy

Other Economic Activity

Lisle Contributes to Beatty's Transportation Economy

The Bootleg Business

Scotty's Castle: "Neither of Us Pays Rent"

People of Beatty

Electric Power and Waste Disposal

Phone Service

Pioneer Educators

Children at Play

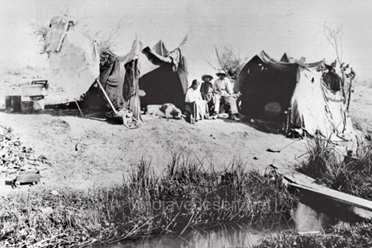

The Beatty Indians in the 1920s and 1930s

Conclusion